WHAT

THE QUESTION OF ART AND TIME IS NOT ABOUT

In

my attempts to encourage philosophers of art to consider the

vital

question of the relationship between art and the passing of time, I

sometimes

meet reactions that suggest an inability to

understand what the

question is about. Having reflected on the problem, I've begun

to

wonder if the cause might be this: the philosophy of art

(especially the

"analytic" variety) has ignored the question for so

long that people have simply forgotten what’s involved – they have

become “de-sensitized”

to it, so to speak.

I’ve

explained my own thinking in my books and some of my

articles, but I’ve also decided to keep a

little log of

some of the comments I’ve encountered as examples of the

misunderstandings. I’m hoping this might help people come to grips with

the

issue. I confess I’m surprised that this is necessary but as the

following points illustrate, even the obvious can be misunderstood in

quite

basic ways.

1. When

I’ve claimed that “time is the forgotten dimension of art”, I've

sometimes

been told that I’m overlooking the fact that many people have

written about

the different ways in which the passing of time is represented in film,

the

novel, music, dance, and so on. On what grounds then, can one claim

that time been forgotten?

This is a

basic misunderstanding. The various ways time is represented in

particular

works concerns the function of time within

individual works (or

perhaps within different art forms: film vs. the novel for instance).

This is

a perfectly valid topic, of course, but quite

different from the

question about the general, external relationship

between art and time.

In the latter case we are looking at how the passing of time – history

in a

general sense – affects art, and specifically how art

transcends

time.

To

illustrate the difference: someone might ask how the passing

of time is dealt with in, say, King Lear or Tom

Jones – which is

a perfectly valid topic in literary criticism. But that's

quite different

from reflecting on the fact that certain works (such as King

Lear

and Tom Jones but also many from centuries

or millennia

earlier) endure, while many others do not, and then

examining

how this occurs. This second question – a question in

art theory

not criticism – has certainly been forgotten in modern aesthetics. One

can search

high and low in books and articles on aesthetics without finding any

discussion

of it.

2. Quite

frequently when I raise the question of the relationship

between art and

time, people assume I’m talking about the so-called

“test of time” –

the attempt to judge the value of a work on the basis of how long it

lasts.

This is emphatically not the issue I'm raising. My question concerns

the

nature of the capacity of art to endure – how

it endures and why;

i.e.

what intrinsic

capacity certain works possess that enables them to live on

and, above all, how that

capacity operates. The dubious notion of a test of time

does not address these questions. In fact, as I explain in my

book Art

and Time, it serves only to muddy the waters.

3. One

comment I received from an academic working in aesthetics was

this: The

question of why art endures is very simple, isn’t it? Certain works

deal with

profound subject matter, offer deep insights, are very

innovative,

skilfully executed, and so on. Works that don’t have characteristics of

this

kind don’t last. Those that do, do. Where’s the problem?

Again, this

misses the point. Even if we accepted the criteria listed (and ignored

their

vagueness and subjective nature) they do not tell us specifically why

art endures.

They could equally well be answers to questions like: Why is one work

of art

good/great, and another not? Or: why does one work give us “aesthetic

pleasure”

(assuming one accepted that questionable notion) and another doesn’t?

In

other words, these criteria don't help us understand, specifically, why

a work

transcends time – i.e. has a special

power to live on across the

centuries. Still less do they throw light on the

crucial question of

the manner of the “living on”, which, as I

explain in my books,

might in principle occur in a number of different

ways.

4. One philosopher

of art asked me why art that endures should be

considered more

admirable, effective, etc than art that doesn’t.

Again, a

confusion between art theory and art

criticism. Whether or not

we find a particular work admirable is ultimately a judgment

we make for

ourselves (whether we appeal to supposed “criteria” or not).

The question

about art’s transcendence concerns the general nature

of art. For

example, we might like or loath Mozart and if someone tells

us that Mozart

has endured, that alone will not (or should not) change our

minds. But it

is nonetheless a simple, observable fact that certain works (much of

Mozart,

for instance) have

endured while large numbers have not, and the question

facing the

art theorist/philosopher is: why does

this happen (i.e. what

particular power do certain works of art possess that

enables it

to happen) and how does it happen

(i.e. in what way do

they endure)? Reflecting on the temporal nature of art – why and how it

transcends time – has nothing to do with handing out plaudits to this

or that

work. It is a question about the general nature of

art.

5. I deal with the following comment in my book, but it bears

repeating

here:

No art is immortal, and no

sensible person could believe

it was. Neither the human race, nor the planet we inhabit, nor the

solar system

to which it belongs, will last forever. From the viewpoint of

geological time,

the afterlife of any artwork is an eyeblink. (John Carey, "What Good

are

the Arts?" London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 2005, 148.)

Carey

(an Emeritus Professor of English Literature at Oxford!)

apparently thinks that the

question of art's capacity to endure is about whether it

endures physically. If

that were the case, art would, of course, fail miserably. The fragility

of many

works has probably made them more vulnerable than

other objects to the

ravages of time. Heaven knows how many great works have

perished over the millennia! The question at

stake has

nothing to do with physical survival; it concerns meaning and

significance:

the capacity of certain works – Macbeth,

Mozart’s Magic Flute,

Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine, for instance – not only to

impress

their contemporaries but also to exert a fascination on subsequent

ages, while

so many other works from the same periods have ceased to arouse

interest and faded into oblivion.

6. A

comment from an “analytic” philosopher on

the idea that (great)

art transcends time:

analytic philosophers would say

that it is

impossible to transcend time, literally speaking, except with time

machines for

example.

One can

only hope that this is not, in fact, the general view

of analytic

philosophers because, if so, it suggests how little serious thought

they

have given to art. (A propos, it’s interesting how susceptible

philosophers of

this persuasion can be to the fantasies of science fiction like time

machines. Food for thought

there...)

7. This

is a recent comment from a contemporary philosopher (of the “analytic”

persuasion, I suspect) in response to something I wrote:

When I post a letter it usually

arrives at the

address to which it is posted a few days later. Now should I think

there is a

significant philosophical question here: What is it that allows the

postal

service to transcend time and deliver a letter on Tuesday that was

written on

Monday? Why do some of my letters arrive and others not? It’s a wonder!

Why is

there anything more of a philosophical problem with

the continued

effectiveness of works of art?

I found

this comment dispiriting because, despite

the writer’s

obvious attempt to be clever, it indicates just how

little thought is

being given to the notion of transcending time in the sense relevant to

art. To transcend time in the relevant sense refers

to the capacity of certain works to remain

vital and alive

despite the passage of long periods of time – to "live on",

in less formal

terminology – like Macbeth or Hamlet,

for example, as

distinct from a play by one of Shakespeares contemporaries

that no longer holds

our interest. A letter in the post does not “transcend time”

when it goes

from one place to another (a decidedly silly thought); it perhaps

“transcends”

distance in some vague sense of the word, but

it merely takes

time. I was genuinely surprised that an academic philosopher –

of

some standing I gathered – could make

a comment as gormless as

this.

8. Here’s

a question someone asked after a paper I gave about

Malraux’s

explanation of the temporal nature of art: So is Malraux

saying that any

object can be a work of art?

I confess I

groaned inwardly at the irrelevance of the question to the paper

I had given. But that aside, let me try

again.

An

explanation of the relationship between art and time – and Malraux’s

explanation in particular – is in no sense an attempt to propose a

priori

principles about what is or is not art (assuming such

principles could be

formulated which is very doubtful**). It is an

attempt to explain, specifically, how works

of art from the past that we continue to admire have endured

– the

manner of their temporal transcendence (taking into account inter alia that

many of them were not originally viewed as “works of art”).

The traditional solution to this problem is that works of art are

“timeless”, impervious

to time, but as I've argued in my books and articles, this is no

longer a viable explanation. So, assuming we don’t simply ignore the

problem

(as modern aesthetics does) how do we solve it? My

answer, as readers of my books and articles will know, is that art

endures through

a process of metamorphosis, as explained by Malraux. But even if one

rejects

this solution, the problem itself does not go away.

One is still

confronted with the unanswered questions: What is the nature

of art's

power of transcendence? How does it work and why?

9. It

dawned on me during question time after a recent paper I

gave that

part of the problem people have in coming to grips with the problem of

the

relationship between art and time is that they have given very little

thought

to the significance of the power of art to

transcend time. It is as if

they feel that, at best, we're just dealing with another

aspect of art, perhaps

even

something rather

humdrum. This is far from the case. What other human creation defies

time – i.e. resists the tide of forgetfulness that sweeps

over everything

else, from the latest fad to social customs to religious beliefs?

Philosophy?

Perhaps. But even that's doubtful. Is there a “perennial”

philosophy,

a set of philosophical tenets common to all ages? Greek philosophy had

a hard

time of it during the Middle Ages, and even now do we endorse

everything that

Plato and Aristotle thought, or even most of it? The special

power of art

to transcend time strikes us particularly forcefully if we think about

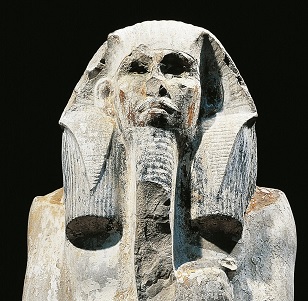

ancient

civilizations such as Egypt. Egyptian customs and beliefs are quite

dead to us

now. We can, of

course, read

books about Egyptian mythology but even that is

like looking at museum specimens: we may learn what Anubis or Seth

etc stood for but we don’t believe in Anubis or

Seth and we never shall – and could not even if we tried. They belong

to what Malraux calls the “charnel

house of dead values”: we find their bones but that’s all. But Egyptian

sculpture

and wall painting is another matter. As in all cultures, some

Egyptian art is mediocre, but the best of it – the most powerful heads

of

pharaohs and the most impressive wall paintings, for

example –

comes

alive

for us: it shares the same mysterious power to move us as

(say) the Victory

of Samothrace, or a Shakespearean play or Mozart. So even

though Egyptian

beliefs are a dead letter to us, their art –

the best of it – is

anything but dead. It has defied time – survived as

something that still

seems vital and alive despite the thousands of years that

separate it from

us. In my book Art and Time, I call this a power

bordering on the

miraculous and it clearly is. I’m not suggesting that it is literally a

miracle. But it is nonetheless truly astonishing.

Art in Malraux’s

words is “the presence in life of what should belong to

death”.

10. When

I gave a seminar paper to ANU Philosophy on Analytic Aesthetics and the Dilemma of

Timelessness, I was genuinely surprised to

discover that a number of

those present seemed to be struggling with the term “timeless”, which

is vital

to the argument. What did I mean by it? Did I just

mean lasting a

long time? I confess I was taken aback. I assumed the

meaning of

the word was well known, especially to people in

the humanities.

Timeless, I

explained, means exactly what it says: time-less,

outside time; exempt

from time and change; impervious to change; eternal. But there

were still

some puzzled looks. "Well," I said (grasping for something that might

help, and remembering I was talking to a group of philosophers), "Think

of

Plato's 'forms'; they are supposed to be unchanging, eternal – unlike

objects

of sense that are subject to change. Same idea here." That seemed to

help

a little.

I’ve since had an inquiry by

email about the

meaning of the term. So let me try again because the idea is essential

to the

traditional understanding of the relationship between art and time

(among

other things).

God – the

Christian God anyway – is said to be

eternal. Indeed, the word is sometimes used as a synonym for God. It

means the

same as timeless (or immortal). It doesn't mean that God ages more

slowly than

the rest of us and will probably live for an unusually long time. It

means that

he has always been, and always will be, because unlike mere mortals, he

is

not affected by the passing of time: he is exempt

from change.

This is not an empirical issue (as my email inquirer seemed to think):

it is

not an observation about the apparent longevity of God; it is an

attribute ascribed

to the deity as deity, as a basic aspect

of his nature. And, as I understand Christian doctrine, those who are

saved will

also live eternally; they will change in nature.

All this

applies to other gods as well of course –

the Greek gods, for example, such as Zeus etc. Hence the well-known

phrase

"the immortal gods".

How does

this relate to art? Very simply. As I say in the paper, the explanation

the

Renaissance gave of the fact that the art of antiquity still

seemed vital

and alive after a gap of so many centuries was that it had a divine

quality – specifically,

it was, like God (or the gods), timeless, eternal, immortal. The

proposition, again, was not that art would last a long time. It was

that art,

like divine things, was impervious to change (not

in the physical sense,

of course: it could be destroyed like anything else). The idea has had

a huge

influence on Western thought, as I point out in the paper, and still

lingers on,

albeit mostly as a cliché (we still hear talk

about "an immortal melody", a "timeless classic" etc). I

argue in the paper that the notion is no longer viable as an

explanation

of how art endures and that we need a replacement. Nevertheless, we

cannot hope

to fully understand large stretches of our cultural

heritage unless

we understand the role of this powerful idea. It is a factor of major

importance in figures as various as Shakespeare, Pope, Hume,

Kant, Joshua

Reynolds (in his Discourses), many of the

Romantics, and countless

others –

including, bizarrely enough, many writers in contemporary

analytic

aesthetics who seem blissfully unaware that they

themselves are relying on it,

this being part of the "dilemma" I refer to in the title of my

paper.

I hope all this helps a little.

Questions are welcome at derek.allan@anu.edu.au

** Many decades of trying by analytic philosophers of art, for example, have brought us no closer. A consensus on what the a priori principles might be is as far away as ever. Not surprisingly...

"A work of art is an object, but it is also an encounter with time."

Biblical figure, Chartres

Horses, Chauvet, 30,000 BC

Sketch, Watteau

Goya, Old people

Giotto. The Kiss of Judas

Poussin. Landscape

Pre-Columbian. 15th century AD. Mask of Quetzalcoatl

Pharaoh Djoser. c. 2630 BC