Analytic

Aesthetics and the

Dilemma of Timelessness

Among

the various schools of thought competing to have their voices heard in

current

debates about the nature and importance of art is the familiar field of

study known

as aesthetics. Like modern philosophy generally, aesthetics splits into

two

main schools – analytic and the continental, although the latter has so

many

varieties it may not be appropriate to call it a school in any strict

sense of

the word.

My

topic today concerns analytic aesthetics not because I think

continental

versions don’t warrant attention but simply because I need to confine

my paper

to manageable limits, and because the problem – the dilemma – I want to

address

today is more clearly illustrated in the case of analytic aesthetics

than in its

continental counterpart.

Some

basic points to begin: Analytic aesthetics, obviously, is an offshoot

of

analytic philosophy. It regularly discusses topics in literature and

music as

well as visual art and often turns its attention as well to general

issues such

as the nature of beauty, the Kantian notion of disinterestedness, the

nature of

“aesthetic pleasure” and so on. Managing the two main academic journals

in the

field – the British Journal of Aesthetics

and the American Journal of Aesthetics

and Art Criticism – analytic aesthetics is probably the most

active school

of philosophical aesthetics in the English-speaking world. Its impact

on neighbouring

disciplines such as art history and literary theory appears to be

limited, but to

the extent that philosophers in

Anglophone

contexts attempt to give an account of art in the general sense of the

word,

analytic aesthetics is probably the principal locus of activity.

My

talk today examines certain assumptions underlying analytic aesthetics

(or the

analytic philosophy of art – the terms are more or less

interchangeable). The issues

I’ll consider are rarely discussed by analytic philosophers of art

themselves –

a matter of regret, as I’ll suggest – but they nevertheless tell us

much about

the field of study in question and the presuppositions on which it’s

based. The

focus of my paper is the relationship between art, in the general

sense, and

time – not time as presented within

works of art (how the passing of time might be represented in a novel

or a film,

for example) but time as an external

factor,

time understood as the changing historical contexts through which works

of art pass,

which in some cases stretch over centuries or even thousands of years.

In the

terminology I’ll employ here, the topic is the temporal nature of art

and a key

objective is to explore the assumptions of analytic aesthetics in this

regard.

What does this school of thought have to say about the temporal nature

of art?

What account does it give of the relationship between a work of art and

the effects

of historical change? Relatively specific though they seem, these

questions, I

believe, take us to the heart of analytic aesthetics and reveal some of

its major

characteristics.

The

temporal nature of art, in the sense I’ve indicated here,

is by no means a new topic. It has an important history and although

that

history is rarely considered by philosophers of art of either the

analytic or the

continental stamp, it’s easy enough to trace. It begins with the

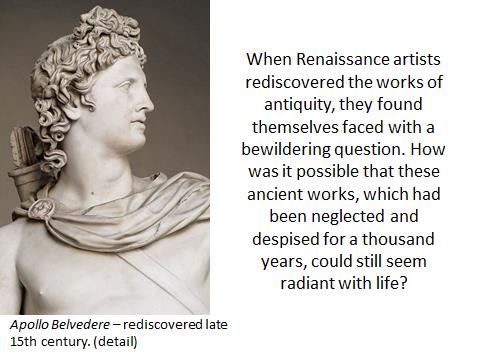

Renaissance. When

Renaissance artists rediscovered the works of antiquity – when they

eagerly dug

time-worn statues from the ruins of ancient Rome, or found new and

unsuspected beauties

in classical authors such as Horace and Plato –

they found themselves faced with a bewildering question. How was it

possible that

these ancient works, which had been neglected and despised for a

thousand

years, could still seem radiant with life? How had their peerless

beauty (for “beauty”

was the quality the Renaissance ascribed to them) survived across such

expanses

of time? The answer the Renaissance gave – an answer that would prove

hugely

influential in Western thought – was that unlike other objects, a work

of art has

a divine quality: art in all its forms, it was decided, is immune from

the passage

of time. It may, of course, be broken, destroyed or lost, but if it

survives,

its beauty is impervious to change.

Art

possesses the quite extraordinary feature that it exists outside

time. In terminology that would become standard for

centuries to come (but which would certainly have shocked medieval

minds for

whom divine qualities belonged to God alone) art is timeless, immortal,

eternal.

The

philosophical discipline called aesthetics was not

invented in its modern form until the eighteenth century but the

Renaissance had

no need of it to celebrate its discovery. I remember studying

Shakespeare’s

sonnets at school and encountering lines such as “Not marble, nor the gilded

monuments/Of princes, shall outlive this

powerful rhyme…”, and I remember being told that the idea that a

beautiful poem

is immortal was simply a flight of Elizabethan poetic fancy, a “poet’s

conceit”

it was called. It was clever, certainly, but not to be taken too

seriously. That,

however, was a misunderstanding because there was much more at stake.

The idea

expressed in lines such as these was central to Renaissance thinking

and explains

why art in all its forms (and the very word “art”) was held in

unprecedented esteem

from then on, and why the idea is found again

and again in other writers

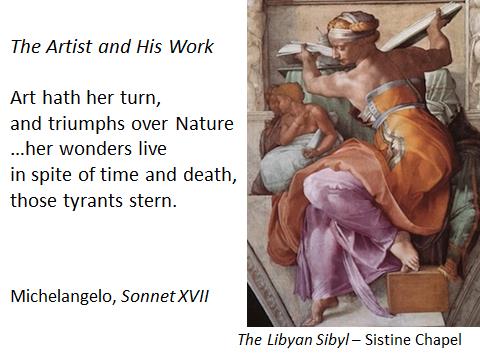

of the times such as Petrarch, Ronsard, Drayton and Spenser – and also Michelangelo who, as well as

being a painter and

sculptor, wrote poetry, and who writes in a sonnet entitled The Artist and His Work that “[art’s]

wonders live in spite of

time and death, those tyrants stern”.[1]

The immortality of art was

an idea that the

intellectual world of the time embraced with enthusiasm. It was part of

the ideology of the Renaissance, if one can

put it that way – as

much a part of the Renaissance world-view as, say, belief in the powers

of

science is for us today.

The idea was, moreover, destined for a long and

illustrious life. So influential was it, indeed, that Romantic poets

were still

celebrating it centuries later, as the French poet and art critic

Théophile

Gautier did, for instance, in his poem Art which proclaims

that “All

things pass. Sturdy art/Alone is eternal”.[2] More importantly for present

purposes, the same

conviction was central to the beliefs of the eighteenth-century

thinkers who

laid the foundations of the philosophical discipline we know as

aesthetics. The

evidence is plain to see. David Hume writes in his well-known and

highly

influential essay Of

the Standard of Taste

that the

function of a suitably prepared sense of taste is to discern that

“catholic

and universal beauty” found in all true works of art, and that the

forms of

beauty thus detected will “while the world endures … maintain their

authority

over the mind of man”, a proposition Hume supports by his familiar

dictum that

“The same Homer who pleased at Athens and Rome two thousand years ago,

is still

admired at Paris and London”.[3]

This belief was undisputed – indeed, by this time, it was simply taken

for

granted – and it received endorsement from a chorus of other

Enlightenment voices

including the influential art historian of the times, Johann

Winckelmann, the

poet Alexander Pope, the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses on Art and Immanuel Kant in

his Critique of Judgement. In

short,

where the relationship between art and the passing of time is

concerned, the

Enlightenment gave a firm stamp of approval to the well-established

view. The

Renaissance had declared art immune from time – timeless, eternal,

immortal – and

the Enlightenment was in full accord.

Now,

aesthetics as we know it today,

especially aesthetics of the analytic variety is, as I’m sure you know,

in a direct

line of descent from eighteenth

century thinkers

such as Hume and Kant and if one had any doubts about that, one would

only need

peruse the two journals I mentioned earlier where articles on aspects

of Hume, Kant

and their contemporaries are part of the staple fare. Two obvious

questions arise

therefore: Does modern analytic aesthetics endorse

the view of its Enlightenment forefathers that art endures timelessly?

And if

not, does it offer an alternative explanation?

Before

looking more closely at those questions, I’d like to pause a moment to

reflect

on the significance of the issues at stake. Let us consider the history

of

literature, for example. We know that of the thousands of novels

published in

the eighteenth century (for instance), only a tiny fraction holds our

interest

today, and that for every Tom Jones

or Les Liaisons dangereuses, there

are large numbers of works by contemporaries of Fielding and Laclos

that have

sunk into oblivion, probably permanently. And if we go a step further

and think

about objects outside the world of art, the point is equally true. We

do not

ask, for example, if a map of the world drawn by a cartographer of the

Elizabethan

era is still a reliable navigational tool, and we know that a ship’s

captain

today who relied on such a map would be very unwise. But we might quite

sensibly ask if Shakespeare’s plays, written at the time the map was

drawn, is

still pertinent to life today, and we might well want to answer yes.

The map

survives as an object of “historical interest” but it’s no longer

applicable to

the world we live in. Shakespeare’s plays, however, are not just part

of

history (although one might also view

them in that light); they have endured in a way the map has not.

So

there is something very real and important at stake here, which applies

not

only to literature, of course, but to art in all its forms. One of

art’s

specific characteristics, we are entitled to say, is a power to endure

– to defy,

or transcend, time – and this is something our experience confirms

every time

we respond to a great work of art from the past. The nature

of this power is a separate question: as we’ve seen, the

Renaissance and the Enlightenment believed that art endures because it

is

exempt from time – timeless – and we shall see shortly that this is not

the

only possibility. But setting that question aside for the moment, one

can at

least say that the power to transcend time is a specific

characteristic of art, a characteristic as real and

evident as any that aesthetics, rightly or wrongly, traditionally

ascribes to

art – such as a capacity to give “aesthetic pleasure”, to “represent

the world”,

to respond to a sense of taste, and so on. If, in other words, one

wishes to

give a full account of the nature of literature, or of art generally,

the capacity

of certain works – those of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Titian,

Mozart,

Monteverdi and many others – to transcend time is one that cannot be

ignored.

There

is another, related point. As I’ve mentioned, timelessness is not the

only conceivable

way art might endure. In principle at least, art’s power of endurance

might

operate in a number of ways. Works of art might,

for example, endure for

a predetermined lengthy period then disappear definitively into

oblivion. They

might endure for a time, disappear, and then return – in a cyclical

way. They might

endure timelessly – the alternative under consideration at the moment.

And, as

we shall see later, there is at least one other possibility. So, by

itself,

a recognition that art has a special power to endure, important though

that is,

leaves us with an unanswered question, an explanatory gap. How,

one needs

to know, does art endure? Or to put the matter slightly differently:

What does

enduring mean in the case of art? Now, I shall

argue shortly that for us

today, the traditional claim that art is timeless has become

unacceptable, but we

should at least acknowledge that it gave an answer to the question of

what

enduring means. Art endures, it said, not simply because it persists in

time in

some unknown, unspecified way, but because it is impervious to

time,

“time-less”, unaffected by the passing parade of history, its meaning

and value

always remaining the same. So whatever one may think about the notion

of

timelessness, it was at least a complete solution. It did not merely

assert that

art endures; it described the nature of

the enduring and the explanatory gap was closed. This, perhaps, is one

of the

reasons why the idea held sway for so long in European culture: here

was an

account of art’s seemingly miraculous power to transcend time that left

no conceptual

questions unanswered.

But

let us return now to the question I left in abeyance a moment ago.

Where does analytic aesthetics

stand on the issue under

discussion? Does it endorse the view of its Enlightenment forefathers

that art

endures because it is timeless? And if not, what alternative

explanation does it

offer? What, in other words, has been the contribution of analytic

aesthetics to this topic which,

as we now see, has a long and important history in Western culture?

Without

doubt, the most striking feature of analytic

aesthetics’ contribution is how slight

it has been. Indeed, the topic

has been all but forgotten. Textbooks seldom discuss it or even carry

an index

reference; the two leading journals, mentioned earlier, rarely carry an

article

with anything more than tangential relevance; and the topic is

conspicuously

absent from courses of study. Many other issues inherited from

Enlightenment writers

are discussed regularly – such as the nature of “aesthetic pleasure”,

whether

disinterestedness is essential to one’s response to art, the meaning of

beauty,

what exactly Hume meant by taste and so on; indeed, these are staples

of modern

analytic aesthetics. But the Enlightenment’s assertion that art is

timeless is

almost entirely ignored, and no alternative is suggested. Thus, a

stream of

thought that had its source in the Renaissance, deeply influenced

Enlightenment

thinking about art and beauty, and carried on through the Romantic

period, has effectively

run dry. Analytic aesthetics displays little or no interest in the

relationship

between art and the passing of time.

Ignoring

an issue, however, does not necessarily make it go away. And, indeed,

there are

clear indications that although analytic aesthetics rarely gives

explicit

endorsement to the Enlightenment view that art is timeless, its practice as a school of thought typically

implies that it accepts this view – or at least that it assumes that

art is atemporal in some unknown

and unexplained

way. Hence the characteristically static feel of analytic aesthetics –

its reluctance

to offer explanations of art that consider historical factors in any

but

peripheral ways, its tendency to focus on topics such as “aesthetic

pleasure”,

disinterestedness, definitions of beauty and so on, that can plausibly

be discussed

without reference to temporal considerations. Hence also a fondness for

the

idea of artistic “universals” – features of art said to transcend time

and

place.[4]

Hence

as well, the tendency

of analytic aesthetics to hold itself at arms’ length from the

discipline of

art history as if to imply that art is best understood in abstract,

timeless or

atemporal terms, free from the distractions of historical

“contingencies”.[5]

Explicit

appeals to the notion of timelessness are infrequent (though not

unknown, as we

shall see in a moment) but in its philosophical practice,

analytic aesthetics’ affinities with Enlightenment

thinking and the assumption that art is timeless are not difficult to

discern.

Now

and then, the notion of timelessness is, however, given something

resembling explicit

approval. Comparing analytic aesthetics to other approaches, one

prominent contemporary

representative of the analytic school writes that the continental

school “is more

historically oriented” while the analytic approach “tends to examine

issues

about the nature of art and the aesthetic qualities of objects in an

ahistorical

manner”.[6]

And

in a similar vein, though with a puzzling “more” qualifying the term

“timeless”,

the same writer argues in a recent issue of the Journal

of Aesthetics and Art Criticism that the value we place on

a work of art is due not just to its historical significance but to its

capacity “to engage the mind, the imagination, and the senses with some

more

timeless interest”, these qualities allowing a work to “enter a more

timeless

canon of literature”.[7]

(I say the word “more” is puzzling here because in the proper sense of

the

word, “timeless” – like “unique” for example – cannot be qualified. Its

meaning

is outside of, or exempt from, time.) Other philosophers of

art occasionally express

similar sentiments. One essay in the British Journal of Aesthetics declares,

for

instance, that “There is a tendency among scholars and non-scholars

alike to

think that art works, or more specifically, great art works, are in

some sense

immortal”, the writer adding that he himself sees “some truth in the

view”.[8]

Another

article in the same journal asserts that “Classics are timeless and

transcendental, appealing to all historical eras, because they capture

what is

essential about humanity”, the

suggestion apparently being that great art is timeless because it

expresses

timeless truths.[9]

Significant

though they are, comments such as these are, nevertheless, the

exception rather

than the rule: in general, as I’ve indicated, analytic aesthetics

simply ignores

the question of the temporal nature of art and passes over it in

silence. Taken

together with the predispositions in philosophical practice

I mentioned above, however, comments of this kind

clearly suggest

that the proposition that art endures timelessly remains very

influential, even

if that fact is rarely acknowledged.

The

question then arises: Can this proposition still be sustained today? Is

it

still plausible to go on believing – or assuming – that art endures

timelessly?

When we think about it, it’s not difficult to imagine why it seemed

very

plausible to Renaissance and Enlightenment minds. Their world of art

was much narrower

than ours, its boundaries extending no further than European art from

the

Renaissance onwards and selected works from antiquity. In these

circumstances,

it was doubtless easy enough to conclude – as in fact it was

concluded – that the reason why the “timeless” works of

antiquity were despised for so long was simply that there had been an

interregnum

of cultural barbarism during which the achievements of ancient Greece

and Rome had

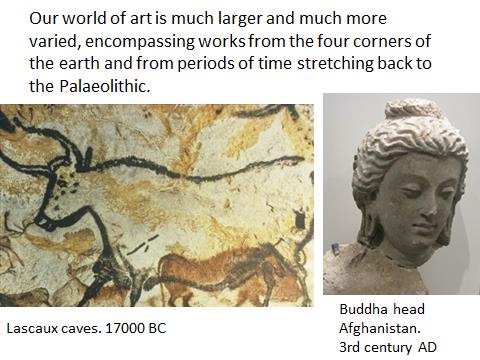

been misunderstood. For us today, however, circumstances are very

different. Our

world of art is much larger and much more varied, encompassing works

from the

four corners of the earth and from periods of time stretching back to

the

Palaeolithic; and we are much less inclined to dismiss the achievements

of earlier

cultures as barbaric, especially since it is from just these cultures

that many

of the objects we now regard as major works of art have come. How

reasonable is

it, then, to endorse the concept of timelessness today?

The

problem can be brought into sharp focus if one thinks of examples in

visual art

where objects have often lasted longer, time scales are lengthier and

the

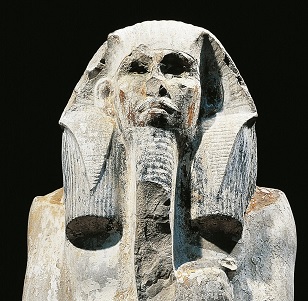

effects of the passage of time more obvious. Consider an ancient

Egyptian sculpture

such as the four-and a half-thousand-year-old statue of the Pharaoh

Djoser now

in the Cairo museum, a work, which despite its battered state, is now

generally

regarded as one of the treasures of world art. What did this statue

mean to the

ancient Egyptians? Doubtless we shall never know exactly given the

difficulties

of fully understanding the world-views of ancient civilizations even

when, as

with Egypt, there is substantial written evidence. We can, however,

feel quite

safe in asserting that the image was not regarded as a “work of art” in

any of

the senses that idea has had for Western culture – first, because we

know that,

like many cultures, ancient Egypt had no word or concept “art”, and

second,

because we know that the statue in question had a purely religious

purpose and

was placed in the pharaoh’s mortuary temple to receive offerings to aid

him in

the afterlife.

Immediately,

therefore, the theory of timelessness receives a major blow. Clearly,

this sculpted

image did not originally have

the meaning and

importance it has for us today: we are not speaking of the “the same

Djoser”,

to adapt Hume’s dictum about Homer that I quoted earlier. But that’s

not the

only difficulty. We today regard the image of Djoser as important

because we consider

it to be a major work of art. But not so long ago – as recently as the

mid-nineteenth century in fact – that judgement would have been

universally rejected.

Nineteenth century art lovers (for whom “art” meant classical

sculptures such

as the Apollo Belvedere and works

of

painters such as Raphael and Titian) excluded Egyptian sculpture from

the

rubric art as rigorously as they excluded objects from tribal Africa,

medieval times,

Hindu India, the Pacific Islands and much more. Objects from cultures

such as

these sometimes found their way into cabinets

de curiosités and, later, into archaeological collections,

but at no point

in European history had they ever

been art: they belonged to the obscure realm of idols and fetishes that

had nothing

to do with art. So, returning to the Egyptian example, not only does

the Pharaoh Djoser have a

significance for

us today quite different from the significance it held in ancient

Egypt, but

there were also long periods of time when, for Western culture, it had

no

significance at all – when, like

countless objects from other cultures we now regard as art, it dwelt in

a

cultural limbo.

Where,

then, does this leave the notion of timelessness – the idea born with

the

Renaissance, vital to Enlightenment aesthetics, and, as we’ve seen,

still

influential in analytic aesthetics today, that works of art are

impervious to time

and change, their meaning and importance unaffected by history?

Clearly, the

idea is left in a parlous state since in cases such as the one just

considered

– and they are legion – time and change have manifestly had a major

effect. And

changing the focus to literature, let’s look again at Hume’s famous

claim. Is it

true that the same Homer – the same

Homer – who pleased at Athens and Rome two thousand years ago was the

Homer admired

in eighteenth century Paris and London – or the Homer we admire today?

The

early history of the Iliad – to

take

that as our example – is rather

obscure but we do know certain

things. We know

that it was originally sung not recited, and certainly not read

silently from the

pages of a book. We also know that the gods and heroes of the story

were figures

in whom the Greeks of the time firmly believed, not personages from

“Greek mythology”

as the eighteenth century saw them, and as we regard them today.

Moreover,

there is little doubt that the modern practice of regarding the Iliad as “literature”, to be placed on

the same footing as epics of other ancient peoples, such as Gilgamesh or the Bhagavad Gita, would have been unthinkable to Greek

communities circa 750 BC

when the Iliad was composed – as

unthinkable as

placing the image of the Pharaoh Djoser in an art museum on the same

footing as

gods from other cultures would have been in the eyes of ancient

Egyptians. How then

do we identify a “timeless” Iliad

persisting

across the millennia unchanged? Where is the immunity from historical

change

required by the notion of timelessness?

Examples

such as Egyptian sculpture and the Iliad

provide vivid illustrations of the dilemma facing the notion of

timelessness

because the time scales are lengthy and the changes dramatic and easy

to see.

But the same issues arise, even if less obviously, when we consider

more recent

works. Is “our” Shakespeare – Shakespeare as we respond to him today –

the same

as the Shakespeare of audiences circa 1600? He certainly seems to

differ from

the Shakespeare of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when

audiences preferred

his plays substantially rewritten, often with different endings –

something we

would undoubtedly balk at today. Closer to our times, how do we square

the

notion of timelessness with Laclos’s Les

Liaisons dangereuses which was attacked for its immorality

when first

published, sank from sight during the nineteenth century with the

advent of

Romanticism, and is now prized for its psychological finesse and rated

as one

of the finest of French novels? And has Dickens’ picture of nineteenth

century urban

life, bleak though it often is, ever seemed quite as bleak since

Dostoevsky

described Raskolnikov’s descent into Hell

in the streets

of St. Petersburg? Examples like this are endless, particularly if one

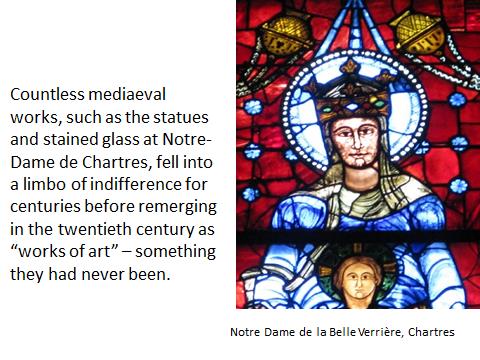

broadens

the scope to include visual art and music. Countless mediaeval works,

such as

the statues and stained glass at Notre-Dame de Chartres, fell into a

limbo of indifference

for centuries before remerging in the twentieth century as “works of

art” – something

they had never been. Vermeer faded from view for over two hundred years

as did

Georges de la Tour. Music has the same tale to tell. The religious

compositions

of Tallis and Byrd disappeared into near oblivion for centuries and are

admired

today as art and not solely for religious reasons as they were

originally. For nineteenth-century

music lovers enamoured of Beethoven and Brahms, Mozart survived

principally as the

standard-bearer for classical restraint – “perfect grace” to employ a

stock

phrase still used by some writers in aesthetics. But is this our Mozart today? “Perfect grace”

hardly seems to do justice to the poignancy of the slow movements of

the piano

concertos, the drama and pathos of Don

Giovanni, the driving energy of the Prague

Symphony, or the haunting grandeur of the Requiem.

And as perceptions of Mozart have changed in recent times,

so have responses to the music of the Romantics: as Mozart alters, so

do

Beethoven and Brahms. Music, in short, is as ill-suited to the

Procrustean bed of

timelessness – of immunity from historical change – as literature and

visual

art.

Two

clear implications flow from all this: first, it seems quite

unacceptable to ignore

the relationship between art and time as analytic aesthetics has done

since its

inception, given that the effects of time are both obvious and

profound; and

second, the traditional explanation of this relationship – that art is

timeless

– is no longer viable. Ingrained in conventional thinking though it

often is,

that explanation has ceased to be believable and something new must be

found. Analytic

aesthetics, regrettably, gives us no help here. Not only, as we have

seen, does

it pay scant attention to the temporal nature of art, but to the

limited extent

it deals with the issue, it simply reiterates the Enlightenment belief,

which

the Enlightenment inherited from the Renaissance, that art endures

timelessly. If

we remain within the conceptual limits of analytic aesthetics,

therefore, we

are left with a dilemma – a major, insoluble dilemma.[10]

My

own belief is that the dilemma is far from insoluble and that a very

persuasive

solution has been offered by the much-neglected twentieth century art

theorist,

André Malraux. I’m not going to attempt to explain Malraux’s account in

detail[11]

partly

because the purpose of my talk is not to proselytize for Malraux’s

theory of

art – worthy cause though that would be – but also because my main

purpose is

to explore the general question of the temporal nature of art and

evaluate the

contribution of analytic aesthetics. It may be useful, nevertheless, to

indicate briefly the nature of Malraux solution if only to show that

there is at

least one serious alternative to the traditional notion of

timelessness.

One

way of approaching Malraux’s position is as follows: If an object is

timeless,

it has an essence that is impervious to change – key elements that

retain the

same meaning and importance across the centuries, even if peripheral

aspects are

sometimes affected.[12]

Empires can rise and fall, customs and beliefs can change radically,

but the

significance of the work – be it literature, visual art, or music –

will always

stay the same. The “same Homer” who pleased at Athens and Rome will be

admired

in eighteenth century Paris and London, and, presumably, endlessly

thereafter.

If there are any lapses in admiration, that would be due simply to an

unfortunate

interregnum of barbarism.

But

it is possible to think of the essence of a work of art in a quite

different

way. Suppose one thinks of it as the characteristic that enables a work

to

endure not by retaining the same meaning and importance across the ages

but by

assuming different meanings and different kinds of importance – “living

on”, as we say, not

by being impervious to change but by responding

to change, by being reborn with new and different

significances.

One

can see immediately how effectively this explanation would deal with

problems of

the kind I have raised. Consider Pharaoh

Djoser again. We saw how badly the timelessness explanation –

perhaps one

might call it the Humean explanation – fared in the face of the fact

that the original

meaning and importance of the image were so different from the meaning

and

importance it has assumed today, and the additional fact that there

were long

periods of time when it had no meaning or importance at all.

Transformations of

this kind – and this example is only one of hundreds – are impossible

to square

with the proposition that art is impervious to time. But if art endures

through change, by means of change, these problems

instantly disappear. For then one

can simply say this: In ancient Egypt, the statue was a powerful

manifestation of

a religious truth. When Egyptian civilization died, so did that

significance of

the image, and since it had no other, it simply lay gathering dust for

four

thousand years. But unlike the customs and beliefs of ancient Egypt,

which have

disappeared forever, the imposing Pharaoh

Djoser has returned to life today and taken on a new meaning

and importance

– as what we call a work of art. Like so many other works of genius

from

earlier cultures – from Buddhist India to Mesopotamia to Romanesque

Europe – it

has shed its original significance and, after a period in limbo,

re-emerged in

modern Western civilization as a work of art, surviving not because it

retains

its original significance, as Hume and his Enlightenment contemporaries

would

have it, but because it has a power of metamorphosis (to employ

Malraux’s term)

– a power of resurrection and transformation that enables it to live

again,

albeit with a meaning and importance of a different kind. The argument obviously

presents a radical

challenge to traditional thinking, but it is neither obscure nor

far-fetched.

As Malraux commented in a television program about visual art in 1975,

For us

today, metamorphosis isn’t something arcane; it stares us in the face.

To talk

about “immortal art” today, faced with the history of art as we know

it, is

simply empty words. Every work has a power of resurrection or it

doesn’t. If it

doesn’t, end of story; but if it survives it’s by a process of

resurrection not

by immortality.[13]

There

is much more to say about Malraux’s concept of metamorphosis[14]

but

I’m hoping that this brief account will be enough to show that there is

certainly

a credible alternative to the notion of timelessness and that the

dilemma

confronting analytic aesthetics is by no means insoluble. But why, we

surely

need to ask, does analytic aesthetics find itself in this quandary? Why

does it

find itself shackled to the unworkable assumption that art is timeless,

or at

least atemporal in some unexplained way?

Evidence

of the kind I’ve discussed today suggests, I believe, that the answer

lies in analytic

aesthetics’ continuing dependence on its eighteenth century origins.

Enlightenment aesthetics, as I’ve said, accepted the Renaissance claim

that art

endures timelessly and when it emerged as a philosophical discipline in

the

eighteenth century, it framed its agenda on that basis, both in terms

of the questions

posed and the kinds of answers given. Consciously or not, analytic

aesthetics

has simply followed suit, choosing

many

of the same issues for discussion and dealing with them in similar ways.[15]

On

the specific question of the temporal nature of art, analytic

aesthetics has usually

been more reticent that its Enlightenment forebears, perhaps because it

is

uncomfortably aware that the world of art as we know it today poses

problems

that Hume, Kant and their contemporaries were never required to face;

but the

general orientation – the static approach discussed earlier, in which

art inhabits

a realm of inert abstractions – nonetheless remains firmly in place.

Analytic aesthetics,

in other words, lives essentially in a world without history, a world

in which

the passage of time is of peripheral importance and where, by

consequence, the

crucial capacity of art to transcend time – one of its key features as

I’ve argued

– is rarely mentioned. Discussion is rigorously confined to issues such

as the

nature of aesthetic pleasure, or the meaning of beauty, or whether the

appreciation of art should be disinterested, or others of that ilk,

which can

be partitioned off from historical change and encased in a tightly

sealed world

where time stands permanently still and where, just as importantly the

question

of art’s capacity to transcend time is never raised.

In

a very real sense, in other words, analytic aesthetics is, in my view,

a

prisoner of a its intellectual inheritance. The writings on aesthetics

of Kant,

Hume and their contemporaries have in many respects assumed the status

of quasi-sacred

texts – works that one may approach as a humble exegete, and even at

times respectfully

disagree with, but certainly not challenge in any fundamental way or

set aside.

This is clearly unsatisfactory. Kant, Hume and their contemporaries did

not

live in a cultural vacuum, and whatever might be said about their

philosophies

in general, their thinking about art, including the relationship

between art

and time, was not immune from the influences of the era in which they

lived –

far from it, as I have suggested.[16]

The Enlightenment took it for granted that art endures timelessly

because no

one had thought otherwise for at least two hundred years, and because,

as I’ve

said, that view doubtless seemed believable at a period in European

history when

the world of art was far narrower than ours. But today the proposition

simply makes

no sense. As Malraux aptly comments, “To talk about ‘immortal art’

today, faced

with the history of art as we know it, is simply empty words.” If

analytic

aesthetics is to escape the realm of empty words, I believe, it needs

to give

careful thought to the Enlightenment inheritance that seems to hold it

in thrall.

Derek Allan

November

2014

References

Allan, Derek. Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's

Theory of Art. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009.

Allan, Derek. Art and

Time.

Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Crowther, Paul. The

Transhistorical

Image. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Symonds, J.A., ed. The

Sonnets of Michelangelo.J.A. Symonds. London: Vision Press,

1950.

[1] J.A. Symonds, ed. The

Sonnets of Michelangelo (London: Vision Press, 1950). Sonnet XVII.

[2] Théophile Gautier: L’Art.

Émaux et Camées. My

translation.

[3] David Hume, Of

the Standard of Taste, and other essays, ed. J.W. Lenz

(Indianapolis:

Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), 9.

[4] Sometimes termed “transhistorical” features.

See, for example: Paul Crowther, The

Transhistorical Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2002).

[5] As one commentator observes, the disciplines

of aesthetics and art

history “pass each other like ships in the night”. Keith Moxey,

"Aesthetics is Dead: Long Live

Aesthetics," in Art History versus

Aesthetics, ed. James Elkins (New York: Routledge, 2006),

166-172, 167.

[6] Peter Lamarque, Analytic

Approaches to Aesthetics: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Introduction.

[7] Peter Lamarque,

"The Uselessness of Art", The Journal of

Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68,

no. 3 (2010),

205-214. 213.

[8] Christopher

Perricone, "Art and the Metamorphosis

of Art into History", British

Journal of Aesthetics, 31, no. 4

(1991), 310-321. 310.

[9] A. Hamilton,

"Scruton’s Philosophy of Culture:

Elitism, Populism, and Classic Art", British

Journal of Aesthetics, 4, no. 49

(2009), 389-404. 403. Analytic aesthetics has a fondness for the

idea of timeless truths.

Like the related notion of human nature, however, the idea has clearly

taken a

severe battering over the past century or so. See my discussion in Derek Allan, Art

and Time (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing,

2013), 141,

142.

[10] Jerrold Levinson, a representative of the

analytic school, attempts

to escape the ahistorical confines of analytic aesthetics by providing

what he

terms an “historical definition of art”. For Levinson, art can be

“defined

historically” via a sequence of “regards-as-art” stretching back into

the past,

his proposition being that “something is art if and only if it is or

was

intended or projected for overall regard as some prior art is or was

correctly

regarded”. The argument quickly collapses in the face of historical

evidence,

given that the concept “art” in anything resembling its modern sense

was

unknown as late as medieval times and absent from a wide range of

non-Western

cultures and early civilizations. The chain of supposed “art regards”

would therefore

peter out long before one reached many of the cultures from which large

numbers

of objects that we today term “art” have come. In other words, this

“historical”

concept of art is essentially unresponsive to history. Jerrold Levinson,

"The Irreducible Historicality

of the Concept of Art", British

Journal of Aesthetics, 42, no. 4

(2002), 367-379; Jerrold Levinson, "Defining Art

Historically," in Aesthetics and the

Philosophy of Art: The Analytic Tradition ed. Peter Lamarque

and Stein

Haugom Olsen (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 35-46.

[11] I have done so in Allan, Art and

Time. Also

in Derek Allan, Art

and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art

(Amsterdam: Rodopi,

2009), esp. Chapter Six.

[12] For example, the language of Shakespeare’s

plays often seems

antiquated today; but the theory of timelessness can accommodate this

simply by

saying that the essence of each of the plays – their core meaning – is

unaffected.

[13] André Malraux, Promenades

imaginaires dans Florence. (Television series: Journal de Voyage avec

André

Malraux.) (Paris: Interviewer: Jean-Marie Drot 1975).

[14] It is important to see that Malraux is

speaking about metamorphosis

as an endless process (so that even the condition “work of art” is not

a

terminus). Peter Lamarque, one of the few analytic writers who

occasionally addresses

questions related to the temporal nature of art, argues that a work

starts out

with “pragmatic” value and gradually takes on “artistic” value, or

value “for

its own sake”. The terms themselves pose obvious difficulties but, in

any case,

one is still restricted to the notion of timelessness since the

“artistic

value” phase is apparently permanent. Peter Lamarque,

"Historical Embeddedness and

Artistic Autonomy," in Aesthetic and

Artistic Autonomy, ed. Owen Hulatt (London: Bloomsbury,

2103), 51-63.

[15] Hegel, Marx and their successors, who

introduced an historical

dimension, and who have been influential in continental aesthetics,

have been

of marginal importance in the analytic context.

[16] Arguably, other

aspects of their thinking were also heavily influenced by the cultural

context.

The notion of taste and the proposition that art exists simply to

afford a

certain kind of pleasure were very much “in the air” in the eighteenth

century.

These issues are beyond the scope of the present essay.

A paper presented to a seminar in the School of Philosophy at the Australian National University, 11 November 2014.

Comment 10 on this page is also relevant.The issues I’ll consider are rarely discussed by analytic philosophers of art themselves – a matter of regret, as I’ll suggest – but they nevertheless tell us much about the field of study in question and the presuppositions on which it’s based.

The temporal nature of art, in the sense I’ve indicated here, is by no means a new topic. It has an important history and although that history is rarely considered by philosophers of art of either the analytic or the continental stamp, it’s easy enough to trace.

The answer the Renaissance gave – an answer that would prove hugely influential in Western thought – was that unlike other objects, a work of art has a divine quality: art in all its forms, it was decided, is immune from the passage of time. ... art is timeless, immortal, eternal.

... the same conviction was central to the beliefs of the eighteenth-century thinkers who laid the foundations of the philosophical discipline we know as aesthetics.

... aesthetics as we know it today, especially aesthetics of the analytic variety, is in a direct line of descent from eighteenth century thinkers such as Hume and Kant

One of art’s specific characteristics, we are entitled to say, is a power to endure – to defy, or transcend, time – and this is something our experience confirms every time we respond to a great work of art from the past. The nature of this power is a separate question ...[but] one can at least say that the power to transcend time is a specific characteristic of art, a characteristic as real and evident as any that aesthetics, rightly or wrongly, traditionally ascribes to art.

In principle at least, art’s power of endurance might operate in a number of ways... So, by itself, a recognition that art has a special power to endure, important though that is, leaves us with an unanswered question, an explanatory gap. How, one needs to know, does art endure?

What has been the contribution of analytic aesthetics to this topic which, as we now see, has a long and important history in Western culture? ... Without doubt, the most striking feature of analytic aesthetics’ contribution is how slight it has been.

... although analytic aesthetics rarely gives explicit endorsement to the Enlightenment view that art is timeless, its practice as a school of thought typically implies that it accepts this view.

Now and then, the notion of timelessness is, however, given something resembling explicit approval...

Is it still plausible to go on believing – or assuming – that art endures timelessly?

The Pharaoh Djoser. 3rd Dynasty

Where, then, does this leave the notion of timelessness – the idea born with the Renaissance, vital to Enlightenment aesthetics, and, as we’ve seen, still influential in analytic aesthetics today, that works of art are impervious to time and change, their meaning and importance unaffected by history? Clearly, the idea is left in a parlous state ...

Mozart survived principally as the standard-bearer for classical restraint – “perfect grace” to employ a stock phrase still used by some writers in aesthetics. But is this our Mozart today?

First, it seems quite unacceptable to ignore the relationship between art and time as analytic aesthetics has done since its inception, given that the effects of time are both obvious and profound; and second, the traditional explanation of this relationship – that art is timeless – is no longer viable.

Suppose one thinks of it as the characteristic that enables a work to endure not by retaining the same meaning and importance across the ages but by assuming different meanings and different kinds of importance – “living on”, as we say, not by being impervious to change but by responding to change, by being reborn with new and different significances.

"For us today, metamorphosis isn’t something arcane; it stares us in the face. To talk about “immortal art” today, faced with the history of art as we know it, is simply empty words. Every work has a power of resurrection or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, end of story; but if it survives it’s by a process of resurrection not by immortality." (Malraux, 1975).

Why does [analytic aesthetics] find itself shackled to the unworkable assumption that art is timeless, or at least atemporal in some unexplained way?... Evidence of the kind I’ve discussed suggests that the answer lies in its continuing dependence on its eighteenth century origins.

Analytic aesthetics lives essentially in a world without history, a world in which the passage of time is of peripheral importance and where, by consequence, the crucial capacity of art to transcend time – one of its key features as I’ve argued – is rarely mentioned.

In a very real sense, analytic aesthetics is a prisoner of a its intellectual inheritance.

Kant, Hume and their contemporaries did not live in a cultural vacuum, and whatever might be said about their philosophies in general, their thinking about art, including the relationship between art and time, was not immune from the influences of the era in which they lived – far from it...