Literature and

the Passing of

Time: Reflecting on the Temporal Nature of Art.

I’d like to approach our topic from a

rather unusual angle – unusual not in the sense that it’s odd or

eccentric, because

I hope it’s neither, but in the sense that it asks questions about

literature and

art in general that the philosophy of art seldom asks, and has not

asked for a

substantial period of time. Fundamentally, what I aim to do is to

approach our

topic via questions about the temporal nature of art – that is,

questions about

the relationship between art and time.

A quick point of clarification to begin:

when I speak about the relationship between art and time, or the

temporal

nature of art, I’m not thinking about the function of time within individual

works –

for example, how the passing of time might be represented within a film

or a

novel, or the function of tempo within a piece of music. I’ll be

speaking,

rather, about a work’s external relationship

with time – that is, the effect of the passing of time on those objects

–

literary, visual, or musical – that we today call works of art. If you

like, I’ll

be talking about the relationship between art and our human past and,

in

particular, the relentless processes of change and forgetfulness that

inevitably

take place across the centuries and millennia.

Now, it’s an odd thing, but there are

certain truths about art that are so familiar to us that we tend simply

to take

them for granted without sparing them a moment’s thought. And the

relationship

between art and time, it seems to me, is one of these. Because we all

recognise

– don’t we? – that works of art have a special capacity to endure over time – to “live on” or

“transcend time”, as we say,

while other aspects of human culture, such as social customs and

beliefs, gradually

die out and fall into oblivion. I don’t mean, of course, that works of

art have

a special capacity to endure physically

because, in fact, they’re often more

vulnerable to damage or destruction than other objects; but they can,

very

obviously, endure in a deeper sense: that is, they can remain vital and

alive despite

enormous intervals of time while other objects created at the same time

are, at

best, of historical interest only.

Now, we are certainly not the first to notice

this remarkable capacity of art. When the Renaissance rediscovered the

works of

antiquity, it found itself faced with the very same surprising

phenomenon. How

was it possible, Renaissance minds asked, that these ancient works,

which had

been ignored and despised for a thousand years, now seemed radiant with

life?

How had they transcended this vast expanse of time? What power made

this

possible? The answer the Renaissance gave – an answer that was to prove

hugely

influential in Western thought – was that unlike other objects, art in

all its

forms is immune from the passing of

time, impervious to change: art,

the

Renaissance decided, possesses the special, and quite astonishing,

characteristic that it exists outside

time: it is, in the terminology that became standard, timeless, eternal, immortal.

Modern aesthetics was not invented until

the eighteenth century, as we know, but the Renaissance quickly found

its own ways

of celebrating this discovery. I remember studying Shakespeare’s

sonnets at

school and reading lines such as “Not marble,

nor the gilded monuments/Of princes, shall outlive this powerful

rhyme…” And I

recall being told that the idea that art is immortal was just a flight

of Elizabethan

poetic fancy, a “poet’s conceit”. But that was quite incorrect because

there

was much more at stake. The idea expressed in lines such as these was a

key

reason why art in all its forms achieved such high esteem from the

Renaissance

onwards, and we find the same idea celebrated again

and again in

other writers of the times such as Petrarch, Ronsard, Drayton, and

Spenser. The

immortality of art was

part of the ideology of the Renaissance, if I can

put it that way – as

much a part of the Renaissance world-view as, say, belief in the powers

of science

is for us today.

Moreover,

the

idea was destined for a long and illustrious life. So influential was

it, in

fact, that one still finds it centuries later in the poetry of the

Romantics.

But more importantly for our purposes, it was central to the belief

system of the

eighteenth-century thinkers who laid the foundations of the discipline

we call

aesthetics or the philosophy of art. The evidence is there for all to

see.

David Hume writes in his well-known essay on the Standard

of Taste that

the function of a suitably prepared

sense of taste is to discern that “catholic and universal beauty” found

in all

true works of art, and that the forms of beauty thus detected will

“while the

world endures…maintain their authority over the mind of man”, a

proposition he

supports by his well-known dictum that “The same Homer who pleased at

Athens

and Rome two thousand years ago, is still admired at Paris and London”.[1] And precisely the same idea is endorsed by

other Enlightenment

figures as various as Winckelmann, Alexander Pope, Sir Joshua Reynolds,

and Immanuel

Kant.[2] In short, where the relationship between art

and time is concerned,

the Enlightenment ratified the Renaissance view. The Renaissance had

concluded that

art is timeless, eternal, immortal, and the Enlightenment was in full

accord.[3]

Now,

as we’re all aware, aesthetics as we

know it today

has been strongly

influenced by Enlightenment figures such as Hume

and Kant, and I would argue that much of what is written today in

aesthetics

and the theory of literature remains deeply beholden to the view

that art is

timeless, even if that fact is seldom acknowledged. But I only

make that

point

in passing because I now want to relate what I’ve said to the topic of

our

conference and particularly to the idea of essence, which is one of our

chief

concerns.

If an object is timeless, it follows

necessarily that it has an essence that is impervious to change. And by

essence

here we cannot mean the minor, peripheral aspects of the object because

that

would imply that the important elements were

subject to change which is contrary to what we are saying. So a

timeless object

would have an essence that remained the same across the ages – key

elements, if

you like, that retain the same significance – the same meaning and

importance –

across the centuries unaffected by the passing parade of history.

Empires could

rise and fall, customs and beliefs could change, but the significance

of the

work – be it literature, visual art, or music – would always stay the

same. Or,

to use Hume’s example again, the same Homer who pleased at Athens and

Rome two

thousand years ago, would still be admired in eighteenth century Paris

and

London – and, presumably, endlessly thereafter.

But there’s a problem, is there not? And

we only have to state the matter plainly, as I have just done, to sense

that

something is not quite right. The problem becomes particularly obvious

if one

thinks in terms of visual art because much more of it has survived for

long

periods of time – here I simply mean survived in the physical sense – and

the

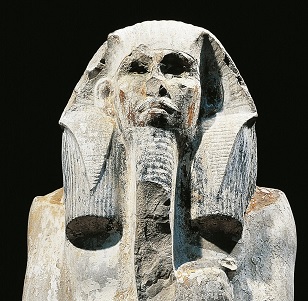

effects of change are easier to discern. Let’s take an ancient Egyptian

sculpture

such as the four-thousand-year-old image of the Pharaoh Djoser which is

now ranked

among the treasures of world art. What did this statue mean to the

ancient

Egyptians? We shall probably never know exactly because it’s so

difficult to

recover the world-view of ancient civilizations even when, as with

Egypt, there

is considerable written evidence. But we can feel quite safe in saying

that the

image was not regarded as a “work of art” in any of the senses that

idea has

for us today, firstly, because the Egyptian language had no word for “art” and, secondly, because

the image was designed for an important religious purpose: it was

placed in the

Pharaoh’s mortuary chapel next to his pyramid to receive the offerings

that

would aid him in the Afterlife.

So here’s a major blow to the theory of

timelessness: clearly, this image did not

always have the meaning and importance it has for us

today. But that’s not

all, and things get even worse. We today regard the image of Djoser as

important because we see it as an important work of art. But not so

long ago that

view would have been universally ridiculed. As recently as the

nineteenth

century, Egyptian sculpture was firmly excluded from the rubric art –

along

with the works of Africa, India, Romanesque Europe, the Pacific

Islands, and

many others. Objects from cultures such as these might find their way

into

cabinets of curiosities or, later, into archaeological collections, but

at no

point in European history had they ever

been art. They belonged in the obscure realm of idols and fetishes that

had nothing

to do with art. So, returning to our example, not only does the Pharaoh

Djoser

have a significance for us that’s very different from the significance

it had

for the ancient Egyptians, but there were also long periods of time

after the

death of Egyptian civilization when, like so many objects from other

cultures, it

had no significance at all – and

when

it was certainly beyond the pale of art.

So where does this leave the notion of

timelessness – the idea born with the Renaissance, and vital to

Enlightenment

aesthetics that works of art are impervious to change? And where does

it leave

the associated notion of an unchanging essence? Clearly, both are left

in a

parlous state. And lest we are tempted to think that literature is not

affected,

let’s reflect on Hume’s famous example. Is it in fact true that the

same Homer

– the same Homer – who pleased at

Athens and Rome two thousand years ago, was the Homer admired in

eighteenth

century Paris and London – or that we admire today? The early history

of the Iliad – to take that as our

example – is somewhat obscure but we do know some things. We know

that it was originally sung not recited, and certainly not read

silently from the

pages of a book. We also know that the gods and heroes of the story

were gods

and heroes in whom the Greeks of the time firmly believed – not simply

“Greek

myths” as the eighteenth century saw them. And there is very little

doubt that the

modern practice of regarding the Iliad

as “literature”, to be placed on the same footing as the epics of other

peoples,

such as the Gilgamesh or the Bhagavad

Gita, would have

been

unthinkable to Greek communities circa 750

BC –

as unthinkable as placing the image of the Pharaoh Djoser in an art

museum on

the same footing as gods from another culture would have been to an

ancient Egyptian.

To what extent, then, can one speak of “the same

Homer”? How exactly do we identify a “timeless” Iliad that has persisted across the

millennia unaffected by social

and cultural change? Where is the unchanging essence? And although I’ve

chosen examples

from the relatively distant past because, as I say, it’s easier then to

see the

effects of time, we encounter the very same questions, even if in a

less obvious

way, in more recent works. Is “our” Shakespeare, for example, the same

as the

Shakespeare of audiences circa 1600? He certainly seems to differ from

the

Shakespeare of audiences from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

who

usually preferred his plays substantially rewritten, often with

different endings

– something we would certainly shrink from today.

And lest we think music is an exception,

let’s take the example of Mozart. For nineteenth-century music lovers,

who saw Mozart

through the prism of Romanticism, Mozart could still be admired (unlike

most

eighteenth century composers) because he was the epitome of

classical

elegance – of

“perfect grace” to employ one the stock phrases, sometimes used by

writers in aesthetics even

today. But

is this

our Mozart? “Perfect grace”

hardly seems to do justice to the poignancy of the slow movements of

the piano

concertos, the sublime fantasy of The

Magic Flute, the driving energy of the Prague

Symphony, or the haunting grandeur of the Requiem.

A different Mozart has emerged for us, and as he has, so our

responses to the Romantics have changed: as Mozart alters, so do

Beethoven

and Brahms. Music, in short, is as ill-suited to the Procrustean bed of

timelessness

as the other arts.

Now perhaps someone might say: “Does any

of this matter? Can’t we just ignore it?” Unfortunately, I don’t think

we can. Because

we are still faced with the simple, intractable fact that, to use the

terms I

used earlier, “works of art have a special capacity to endure over

time, while

other things such as customs and beliefs die out and fall into

oblivion.” For

most of European history since the Renaissance, explaining this special

power posed

no problem because one could simply turn to the concept of

timelessness. But if

we jettison this explanation – and I’ve been seeking to persuade you

that we should–

what do we put in its place? Is there some other way of explaining how

the Pharaoh Djoser, the Iliad, Shakespeare’s plays and so many

other works from the past

have “lived on” – bearing mind that, as we now see, they have not been impervious to change?

I believe there is

an alternative explanation but since my time has nearly run out I

will need to describe it in a very abbreviated way. Fortunately, one

useful way

of approaching the matter is through the idea of essence that is one of

our conference’s

central concerns. When we think of an essence we usually tend to think,

as I

suggested earlier, of something that is proof against change –

something that

resists when all else is transitory. Hence our readiness to link the

idea of an

essence of art to the notion that art is timeless: it would be the

essence of a

play, a painting, or a piece of music that escapes the vicissitudes of

time and

change.

But suppose we think of the essence of

art in a different way. Suppose we think of it as the characteristic

that

enables a work to endure not by retaining the same meaning and

importance

across the ages but, on the contrary, by assuming different meanings

and

different kinds of importance – “living on”, that is, not by being

impervious

to change but by responding to change

by being reborn with new and different significances.

We can immediately see how well such an

explanation

would fit the kinds of facts I’ve been discussing, and why it would

make sense

where, as we have seen, the notion of timelessness fails to do so.

Consider my Egyptian

example again. We saw how badly the timelessness explanation – perhaps

I might

call it the Humean explanation – how badly this explanation fared in

the face

of the fact that the original meaning and importance of the image was

so

different from its meaning and importance today – and the additional

fact that

there were long periods of time when it had no meaning or importance at

all. Transformations

of this kind – and this Egyptian example is only one of hundreds I

could have

used – are simply impossible to square with the proposition that art is

impervious to time. But if art endures through

change – by means of

change – these

problems immediately disappear. Because then we can simply say this:

For the ancient

Egyptians, the image was a powerful expression of a religious truth.

When

Egyptian civilization disappeared, so did the religious significance of

the

image and for four thousand years it simply lay gathering dust. But

unlike the customs

and beliefs of ancient Egypt which have disappeared forever, the

impressive image

of the Pharaoh Djoser has been able

to revive, to take on a new meaning and a new importance – a meaning

and

importance today as what we call a work of art. Like so many other

works of

genius from earlier cultures, from Mesopotamia, to Buddhist India, to

Mesoamerica,

to Romanesque and Byzantine Europe, it has shed its original

significance and,

after a period in oblivion, returned to life in modern Western

civilization as

a work of art, surviving not because it retains its original

significance, as

Hume would have us believe, but because it has a power of metamorphosis

– a

power to live again, albeit with a significance of a different kind.

My time is nearly up so I shall conclude

very quickly. I should stress that the explanation of art’s power to

endure that

I’ve just outlined is not my own invention: it is a key element of

André Malraux’s

theory of art which he explores in works such as The

Voices of Silence

– though in much more depth and detail than

I’ve

done today. But my purpose in discussing Malraux’s theory of

metamorphosis has

not been to proselytize for his theory of art – worthy cause though

that would

have been – but, above all, to draw attention to the neglected issue of

the

relationship between art and time and, in doing so, suggest how that

affects

the question of “essence”. As long as we think of the essence of a work

of art in

the terms implied by Hume’s dictum – that is, as a significance

impervious to

time – we are, I believe, condemned to divorce ourselves from the world

of art

as we now know it and find ourselves clinging to a theory that has

outlived its

usefulness. There is often a tendency, I might say here, to read the

works of

the Enlightenment founding fathers of aesthetics as if they were

quasi-sacred

texts – writings that one can approach as a respectful exegete but not

challenge in any fundamental way. But we need to remember that Hume,

Kant and

their contemporaries did not live and write in a cultural vacuum; much

of their thought reflects the times in which they lived, and

their

thinking about the relationship between art and time is a direct

inheritance

from the Renaissance – an inheritance that doubtless seemed convincing

enough

in the eighteenth century when the world of art was far narrower than

ours, but

an inheritance that, as we have seen, makes no sense at all today. It

is highly

unlikely that the Iliad chanted in

Greece over two thousand years ago is “the same Iliad”

that pleased an eighteenth century philosopher and belle-lettrist

such as Hume, just as it

is highly unlikely that the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, or the saints

in the

porches of mediaeval cathedrals, or Shakespeare or Mozart, meant the

same when

first created as they mean to us today. Large numbers of works of

literature,

visual art, and music have endured – unlike the customs and beliefs

that were

current at the time of their creation; but they have endured not

because they

are timeless but through a process of metamorphosis; and their

“essence” is not

a power to retain an unchanging meaning through time but a capacity to

re-emerge

with new meanings – transcending time not through immortality but

through transformation

and resurrection.

[1]

David Hume, Of

the Standard of Taste, and other essays, ed. J.W. Lenz

(Indianapolis:

Bobbs-Merrill, 1965), 9.

[2] Who writes for

example that “some products of taste” are “exemplary”,

and that there exists an “Ideal of the Beautiful”, the basic conditions

of

which are illustrated by “the celebrated Doryphorus of Polycletus”.

Immanuel

Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment,

ed. Paul Guyer, trans. Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press, 2000), 116-119. (Book One, §17, “Of the Ideal of

Beauty”.) Kant’s emphasis.

Some writers argue that Kant’s comments here are inconsistent with

other

aspects of his argument. They may

well be; they are nonetheless part of what he writes.

[3]

Cf. Pope’s An Essay on Criticism:

Hail! bards triumphant!

born in happier days;

Immortal heirs of universal praise!

Whose honours with increase of ages grow,

As streams roll down, enlarging as they flow;

Nations unborn your mighty names shall sound…

A paper delivered at a conference entitled 21st Century Theories of Literature: Essence, Fiction, and Value, University of Warwick 27th to 29th March, 2014.

Pharaoh

Djoser.

c. 2630 BC