Art, Time and Metamorphosis: A Revolutionary Aspect of André Malraux’s Theory of Art.

The

topic I wish like to address today is one which, it seems to me, should

occupy

a position of major importance on the agenda of modern aesthetics but

which,

oddly enough, is almost completely neglected.

The

topic is the relationship between art and time – or to

use an

equivalent phrase, the temporal nature of art.

What

do I mean by the relationship between art and time?

Well, what I do not

mean is the portrayal

of time within this or that particular work –

for example in Proust’s A la Recherche du

temps perdu as compared with, say, the picaresque novel. That is a perfectly

legitimate topic of

interest of course, but my focus today lies elsewhere.

I want to talk about the general

relationship between art and time – the temporal nature of

art in general.* Given

that such a thing

as art exists – and that much I’m going to take for granted – do we

think that

its temporal nature differs in some important way from that of other

products

of human activity? And

if so how? And why

might this be important?

The

question is by no means strange or esoteric.

There

is one view of the relationship between art and time

that is so familiar

to us that it has almost become a cliché, an idea that we employ

very

often

but to which we rarely give a second thought.

This

is the idea that art – or at least great art – has a

special capacity

to, as we say, ‘endure’ or ‘last’.

We

don’t mean by this, of course, that works of art have a special power

of physical endurance: we know that

they

are as vulnerable to floods, fires, earthquakes or simple neglect as

anything

else. We mean,

rather, that certain works

— Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the Mona Lisa,

Mozart’s Magic Flute,

for example

— seem to have a capacity not only to impress their contemporaries but

also to

exert a fascination on subsequent ages, while so many other works have

lost whatever

appeal they may once have had and have sunk into oblivion. We mean, more broadly,

that unlike so many

other things that the passage of time renders obsolete and void of

interest – ranging

from the latest fashion to beliefs about the nature of the universe –

certain

works of art seem to have a power

to preserve

their vitality, and to escape

consignment to what André Malraux aptly terms ‘the

charnel house of dead values’.[1] In effect they seem to

have a power to transcend time.

In a sense, all

this is a

statement of the obvious: as I say, the idea

that a great work of art ‘endures’ is so familiar to us that we rarely

give it

a second thought. Yet once we begin to reflect on the proposition, it

is surely

a perplexing one – a proposition that puzzles the understanding. How, after all, could

certain works

‘transcend time’? What precisely does that mean? What property could

such works

possess that might bring that about? How does it operate? And what significance might we

place on

this apparent power to defy the vicissitudes of time?

We are not, of

course, the

first to have wondered about the temporal

nature of art and it is useful, I think, to remind ourselves of the

leading

ideas on the subject that our Western cultural inheritance has

bequeathed to

us.

Perhaps the most

influential idea owes its power, if not its origins as

well, to the Renaissance. How

was it

possible, Renaissance minds asked themselves, that the rediscovered

works of

Greece and Rome – forgotten for a thousand years and more – seemed

suddenly

radiant with life, as if, somehow, they had defied the passage of time?

What

power did these works possess that could make such a thing possible? The answer the Renaissance

gave has echoed

down the centuries and is still very much part of our intellectual

heritage. The works

of Antiquity, like

those that the Renaissance artists were themselves bringing into being,

were,

it was said, possessed of a demiurgic power called “beauty”, and

beauty, like

the goddess Venus so often chosen as its supreme representative, is

“immortal”.

The works of Antiquity, like the paintings of a Botticelli or a

Raphael, were

all works of “art” — a term on which the Renaissance was conferring a

new significance — and each of them bore triumphant witness to

the power

of beauty to accede to an eternal

realm, impervious to the corrosive powers of time. This thinking was

not just

the preserve of a handful of intellectuals.

It

had all the force of a reigning ideology — as powerful

and as widely

accepted as, say, Marxist and post-Marxist explanations of history have

been

for large numbers of people over much of the past century. We find the idea again and

again in

Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example, and it was still very much alive in

the

mid-nineteenth century when Théophile

Gautier could write in his poem called ‘Art’:

All things pass. Sturdy art

Alone is

eternal;

The sculpted

bust

Outlives the State.[2]

As I have suggested, the impression this pattern of thinking has left on Western culture has been deep and lasting. In the eighteenth century, when, somewhat belatedly, philosophers began to offer a systematic account of art — to be christened “aesthetics” — the notion of beauty was at the core of its explanation, and writers took it for granted that the finest works foregathered, along with those of Greece and Rome, in a timeless or eternal realm of balance, order and harmony, sometimes called the realm of the beau idéal. And whether we are aware of it or not, the influence of this thinking is still very much with us today. Our contemporary vocabulary has changed somewhat, and references to Greek mythology are usually omitted, but for many critics and aestheticians today, art is still explicable essentially in terms of ‘beauty’; and while most writers would, in our hard-headed, down-to-earth, age, probably shrink from terms such as ‘immortal’, ‘eternal’ or maybe even ‘timeless’, there remains, as I have said, a widespread, if seldom clearly formulated, assumption that a true work of art is one that possesses a capacity to ‘last’ or ‘endure’, which its weaker rivals do not.The

question that confronts us today is whether this explanation of the

temporal

nature of art remains satisfactory and, if not, what account might we

put in

its place. Given

that, as we have said,

art appears to possess some special capacity to endure – to transcend

time – and given also that we

are looking for an explanation and that we’re not, like much

contemporary

aesthetics, simply turning our backs on the problem, do we think that

the

traditional explanation I have outlined – the notion that art is

beauty, and

beauty is timeless – remains plausible for us today?

And if we don’t think that, what explanation

might we now offer for the apparent

power of art to transcend time? How

in

short might we explain the temporal

nature of art?

I

believe the traditional explanation I have described is no longer

viable and

that there are at least three reasons why this is so.

I shall outline them briefly in increasing

order of importance.

First,

the last hundred or so years has witnessed the progressive

disintegration of

the idea that art is the manifestation of ideal beauty – an idea which,

as I

have said, has been a mainstay of the traditional explanation. The notion of a beau idéal

began to lose plausibility in the early decades of the

twentieth century when the category ‘art’ started to encompass works

which no

longer seemed to have any connection with such an ideal — that is, when

the

boundaries of art began to extend beyond Raphael, Titian and their

post-Renaissance successors to take in the worlds of (for example)

Pre-Columbian gods and African masks, modern artists such as Picasso,

and

pre-Renaissance Western art such as Romanesque sculpture or medieval

paintings

such as the Isenheim Altarpiece. I

am aware that some contemporary advocates

of the theory of beauty attempt expand the theory to accommodate works

such as

these, but the result is a concept of beauty that seems to me so vague

and

anaemic that it ceases to be of any explanatory value.

The

second assault on the traditional explanation of the temporal nature of

art has

come from the modern fascination with the idea of history – a major

focus of

nineteenth century thought and one that, in many respects, we continue

to

share. Though

seldom stated plainly and

simply, the threat this idea poses to the traditional explanation is

perfectly

straightforward. If

something is

understood

as timeless, then essentially it is exempt from change: it is

unaffected by the

vicissitudes of time and circumstance.

If

art is timeless, it must therefore lie essentially outside

history and beyond the reach of

history’s explanatory categories.

Naturally

enough, this implication is not at all congenial

to theorists

who place history at the centre of their thinking

and

it was, for example, quite unacceptable

to Hegel, who placed art firmly within

the ambit of history and made it the subject of a teleology — ending,

indeed,

with art’s demise; and of course the assaults on the notion of

timelessness

continued with Taine and Marx and a series of post-Marxist thinkers up

to the

present day, all of whom have declined to exempt art from the

historical

process (however conceived). Art,

on the

historical view of things, is fundamentally a creature of its times. No less — and perhaps even

more — than other

human activities, it bears the marks of its times, and plays its part

in

strengthening or subverting dominant ideologies and social arrangements. To locate its essential

qualities in a

changeless, ‘eternal’ realm removed from the flow of history would from

this

point of view, be an ‘idealist’ illusion, false to art and history

alike.

The

third attack on the traditional explanation seems to me the most

damaging of

all.

The

nature of the problem quickly becomes clear if we take account of the full extent of the realm of art as we

know it today. “Art”

today no longer

simply means, as it did for several centuries, the works of the

post-Renaissance West plus selected works of

A

further example may perhaps help clarify the point.

The so-called “pier statues” of biblical

figures on the exterior of the cathedral of Chartres are today

considered to be

among the treasures of world art, on a par with works such as the

frescos at

Ajanta, the best of Egyptian or Khmer sculpture, and the works of

Donatello or

Michelangelo. Yet

from Raphael onwards all medieval

art, including

***

Now,

as I mentioned at the outset, the question of the temporal nature of

art has

been almost entirely neglected in contemporary aesthetics so it is very

difficult to locate books or articles which address the issues I have

been

discussing. To my

knowledge, the only

exception to this is the French writer and art theorist, André

Malraux, for

whom the relationship between art and time is a matter of central

concern. Much of

what I have already said

today is

informed by Malraux’s theory of art but in the brief time remaining I

would

like to say a little more about his thinking on this matter.

Malraux’s

firmly rejects the proposition that the temporal nature of art can be

explained

by the notion of timelessness, and one of the central themes of his

theory of

art is that art transcends time not because it is unaffected by the

vicissitudes of time and circumstance, but through a process of metamorphosis in which time and change

play an intrinsic and inevitable part.

If

time had permitted I would have liked to provide a full

explanation

of this aspect of Malraux’s thinking showing how it emerges as a

necessary

consequence of the basic propositions on which his theory of art rests. This is especially worth

doing because some

of Malraux’s commentators – E H Gombrich is a prime example – have

claimed that

he is not a systematic thinker but merely a purveyor of random

insights, an opinion which, I believe, is demonstrably

false. Unfortunately,

however, time will

not permit

the kind of in-depth explanation a refutation of that kind would

require, so I

thought I would confine myself to certain key propositions about the

temporal

nature of art that emerge from Malraux’s thinking and simply trust that

you

will accept my assertion that, like all other aspects of his thinking

about

art, they form part of one coherent, systematic theory.

As

I have said, Malraux argues that art transcends time through a process

of

change – of metamorphosis. To

quote one

of his formulations, he writes in the third volume of The

Metamorphosis of the Gods,

entitled L’Intemporel, that

‘Metamorphosis is the very life of the work of art in time, one of its

specific

characteristics.’[4] What exactly does this

mean? One way of

clarifying his position is to

distinguish it from a very familiar claim about the interpretation of

works of

art with which it might perhaps be confused.

We

have all no doubt encountered the idea that a

particular work of art

may be given different interpretations at different periods of time –

that a

play by Shakespeare, for example, can be interpreted in a variety of

ways and

that successive periods of history are likely to see it in different

lights and

discover different meanings in it.

Well,

one might say, is this all Malraux is saying when he writes that

metamorphosis

‘is the very life of the work of art in time’?

Is

he simply rehashing this familiar truism?

The

answer is an unequivocal no,

because the similarity between this and Malraux’s position is purely

superficial. Malraux

certainly accepts

that different historical periods may discover different meanings in a

work of

art and perhaps regard it with varying degrees of importance –

including, quite

possibly, none at all. But

by itself, if

we reflect on it, that familiar proposition tells us nothing

specific about the temporal nature of art.

It

is perfectly compatible, for example, with

the claim, which is quite at variance with Malraux’s position, that the

work of

art is something whose nature is fixed ‘once and for all’; for one need

only

assume that different interpretations to which a work lends itself is a

specific, fixed range of meanings

that the artist, consciously or unconsciously, gave it at its moment of

birth. Malraux does

not leave the matter

unresolved in this way. He

is arguing

that the work of art is something which,

by its very nature – and not simply as a result of accidental

circumstance

– has a changing significance. It

is a

domain of meaning that is inherently

in a state of continual change. ‘Metamorphosis’,

he writes in The

Voices of Silence, ‘is not an accident, it is the very law of

life

of the

work of art.’[5]

It follows then that a work’s significance at its moment of birth is only that – its original

significance –

and one that will, whether the artist knows

it or not, inevitably disappear over time, to be replaced by another. The work’s moment of

creation, whatever

effect it may then produce, and whatever function it may then perform

(which in

many cultures may not even be as

‘work of art’ as we have noted) is only a point of departure

from which

it sets out on a journey of metamorphosis.

Its

nature is precisely that of an adventure launched onto

the unknown

seas of the human future : like an adventure, it is not proof against

time and

changing circumstance (as the concept of timelessness would require)

and there

may well be times when it fades into obscurity, possibly for centuries,

even

millennia. But like

an adventure, it is

pregnant with possibility: unlike

the

mere historical object which fades into oblivion, it is capable of

‘living

again’, albeit with a significance quite different from that which it

originally possessed.

Thus,

a work may, for example, begin its life as a sacred object within a

particular

religious context – a Pharaoh’s ‘double’, for instance, placed in his

mortuary

chapel to receive the offerings of his subjects.

Subsequently,

when the beliefs on which that

significance depended have perished, the object may recede into

obscurity, as

did the works of Ancient Egypt for nearly two millennia, or as

Byzantine art

did after Giotto, or as Giotto himself faded from view for nearly three

centuries after Leonardo and Raphael.

In

such cases, it is as if the work inhabits, for a time, a kind of limbo

in which

it evokes at best indifference, at worst, contempt.

But unlike the mere historical object, it is

capable of resurrection, and it returns to life if and when, with the

passing

of time and its own capacity for metamorphosis, it can re-emerge, but

with a

significance quite different from that which it originally possessed. Thus the works of Ancient

Egypt, Byzantium,

and Giotto ceased in time to be sacred images, created for tomb,

basilica, and

chapel, and became, after periods of obscurity, ‘works of art’ in the

sense

that phrase has for us today. Seen

in

this light, the destiny of any great work, Malraux argues, is

inseparable from

a dialogue – though at times a

dialogue of the deaf – between the changing human present, and the

work’s own,

continually changing significance.

We

recognise,

he writes,

That

if Time

cannot permanently silence a work of genius it is not

because the work prevails against Time by perpetuating its original

language

but because it constrains us to listen to a language constantly

modified,

sometimes forgotten – as it were an echo answering each century’s

changing

voice – and what the great work of art sustains is not a monologue,

however

authoritative, but an invincible dialogue.[6]

One

such dialogue which is very familiar to us is that which led to the

revival of

Greek and Roman art during the Renaissance, and Malraux’s explanation

of the

temporal nature of art allows us to see this event in a very different

light

from that in which it is conventionally portrayed.

Renaissance art, we are often told, was stimulated

by the discovery of the works of Antiquity.

But

what exactly does ‘discovery’ mean in this context?

Malraux asks.[7] Traditional accounts

sometimes give the

impression that the works of

The

most dramatic example of such a dialogue has, of course, taken place in

our own

time which has seen the resuscitation, as works of art, of objects from

the

four corners of the earth and from the depths of ancient history and

prehistory, large numbers from cultures in which the notion of art was

quite

unknown. The

significance of this

unprecedented event, and the reasons why it occurred when it did, are

explored

at length in Malraux’s books on art and I could not hope to do justice

to those

matters today. The

key point once again,

however, is that he sees this development in terms of dialogue and

metamorphosis, resulting this time in what he does not hesitate to call

‘another Renaissance’,[10]

recognising of course that the scope of our modern resuscitations

dwarfs those

of the Renaissance.

***

Malraux’s

theory of art poses a series of major

challenges to modern aesthetics, and there is much more to be said on

that

topic than I have covered today. Among

the many challenges, however, his explanation of the temporal nature of

art

stands out as one of the most striking and important.

As we have seen, the traditional

explanations

we have inherited simply

do not account for the facts as we know them.

Art

clearly does not live ‘eternally’, and nor is it

swallowed up

irrevocably, as a mere historical phenomenon, into ‘the charnel house

of dead

values’. And

neither of those

explanations even begins to explain why, when resurrected, so many of

the

objects we today regard as art have assumed a significance quite

different from

that which they originally held – that a god or an ancestor figure, for

example, has become ‘art’. Malraux’s

theory of art provides a solution to this problem.

He allows to see why art ‘conquers time’ –

why we find (for example) Sumerian religious figures thousands of years

old in

our art museums (and not just as archaeological artefacts in history museums); yet at the same time

he frees us from having to believe what now seems a manifest absurdity

– that

art is eternal.

As

I mentioned earlier, the question of the temporal nature of art has

been pushed

very much to the margins of modern aesthetics.

Indeed,

the last major contribution to the topic was

arguably that of Hegel

who placed art firmly in the domain of history.

Broadly

speaking, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries

have had to

make do either with variations on Hegel – Arthur Danto is one example[11]

– or with Marxist and post-Marxist accounts which, again, situate art

essentially within the domain of history.

The

other alternative has been the almost complete

indifference to the

question shown by contemporary analytic aesthetics.

Meanwhile,

however, over the course of the past hundred years, and almost as if to

mock

the inadequacy of these explanations, art museums around the world have

been

filling up with objects from distant times and other cultures which

seem to

have escaped history (because, though long-forgotten, they have ‘come

alive’

for us today) but which are self-evidently not timeless (because they

have been

resurrected after long periods of oblivion with significances quite

different

from those which they originally held).

In

other words, art museums around the world have been

filling up with

objects whose very presence there poses

the problem of the relationship between art and time in an acute and

very conspicuous way.

The

outstanding

value of Malraux’s contribution is not only

that he

recognises the pressing need to address this matter, but that he

provides a

solution that fits the facts as we know them.

He

has given us a fundamentally new way of understanding

the

relationship between art and time, which, unlike the explanations

bequeathed to

us by our Western cultural heritage, makes sense of the world of art as

we now

know it. His

account of the temporal

nature of art thus stands out as a landmark achievement in the theory

of

art. It is no

exaggeration, in my

view, to describe his contribution in this area as revolutionary.

* In other words the external

relation between art and time - the relation between art and

the passing of time - with history in the broadest sense.

[1] André

Malraux, Les Voix du silence,

Ecrits sur l’art (I), Jean-Yves Tadié, ed., 2 vols (Paris:

Gallimard, 2004)

890.

[2] Théophile Gautier: Émaux et Camées, 1852. ‘L’Art’.

[3] “How comprehensively Gothic art was ignored by

the

nineteenth

century!” André

Malraux writes.

“Théophile

Gautier, passing by

[4] André Malraux, La

Métamorphose des dieux: L’Intemporel, Ecrits sur l'art (II),

ed.

Henri Godard (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), 971.

[5] Malraux, Les

Voix du silence, Ecrits

sur l'art (I), 264.

[6] Ibid, 264

[7] André Malraux, "Appendice aux

'Voix

du silence': Premières ébauches inédits," in Ecrits

sur l'Art, ed. Jean-Yves Tadié (Paris:

Gallimard, 2004),

904.

[8] Malraux, Les

Voix du silence, Ecrits

sur l'art (I), 261.

[9] Ibid., 484.

[10] The Psychology of art,

Museum

without walls, 142.

[11] Part of Danto’s theory of art consists of a reinterpretation of Hegel’s end of art thesis. See, for example, Arthur Danto, After the End of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), esp. 30-34.

This

paper was delivered at the annual conference of The Nordic Society of

Aesthetics in Uppsala University, Sweden, 29 May to 1 June 2008.

It outlines, in an abbreviated form, some of the arguments I advance in my book Art and Time.

We

don’t mean that works of art have a special power

of physical endurance... We

mean that certain

works

— Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the Mona Lisa,

Mozart’s Magic Flute,

for example

— seem to have a capacity not only to impress their contemporaries but

also to

exert a fascination on subsequent ages...

... once we begin to reflect on the proposition, it is surely a perplexing one – a proposition that puzzles the understanding. How, after all, could certain works ‘transcend time’?

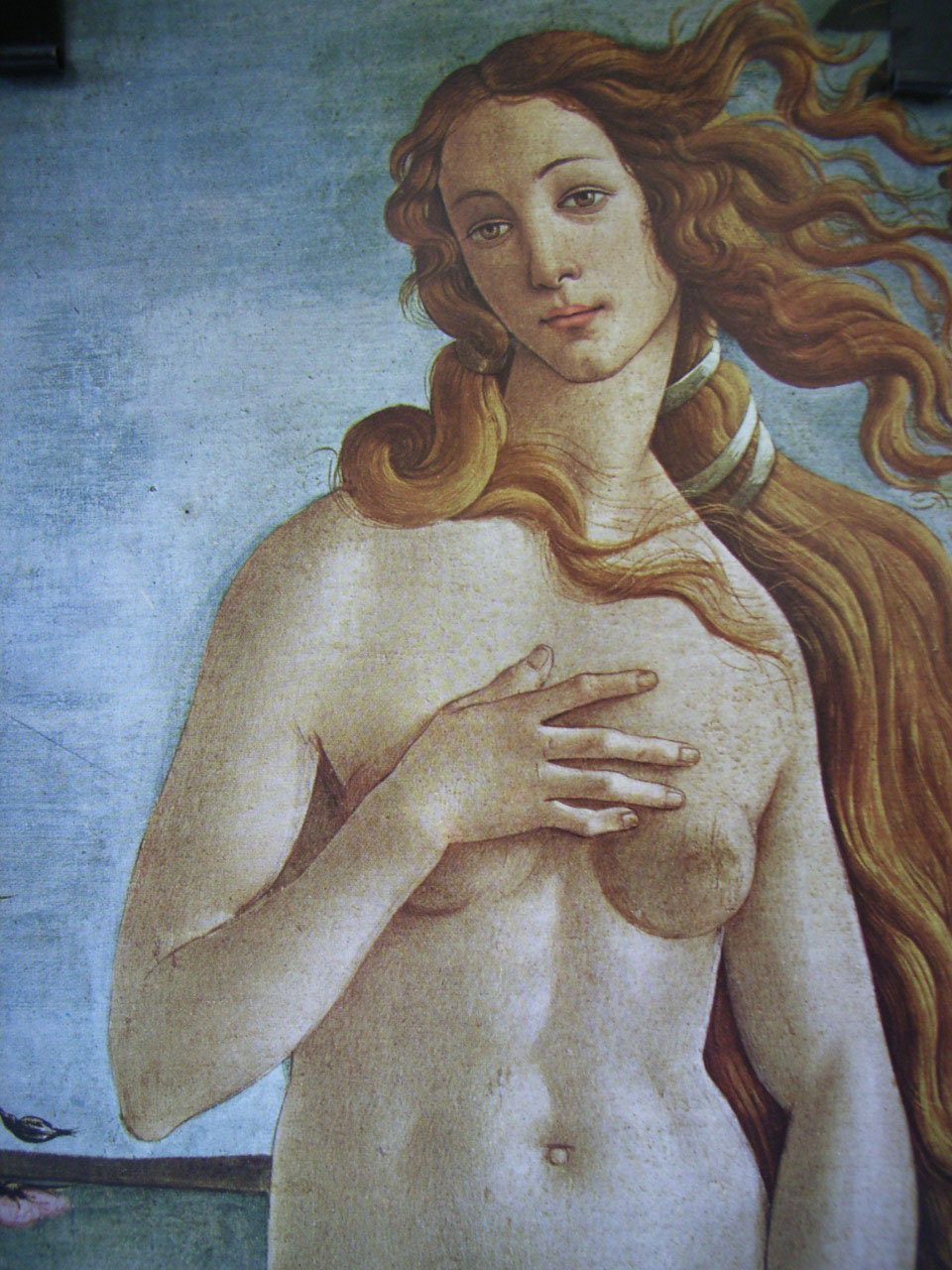

Birth of Venus – Botticelli (detail)

... what explanation might we now offer for the apparent power of art to transcend time? How might we explain the temporal nature of art?

Raphael

– Madonna del

Belvedere

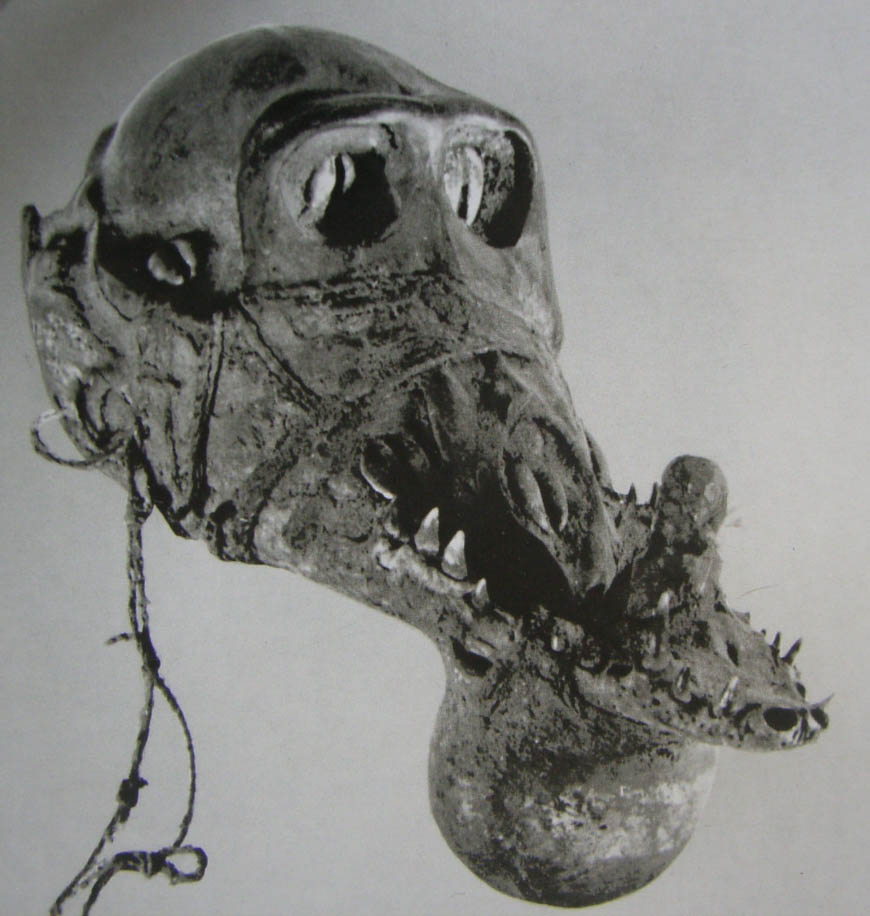

Voodoo mask, Fon people,

Art today encompasses the works of a wide range of non-Western cultures, many ancient civilizations, and even Palaeolithic times stretching back to the caves of

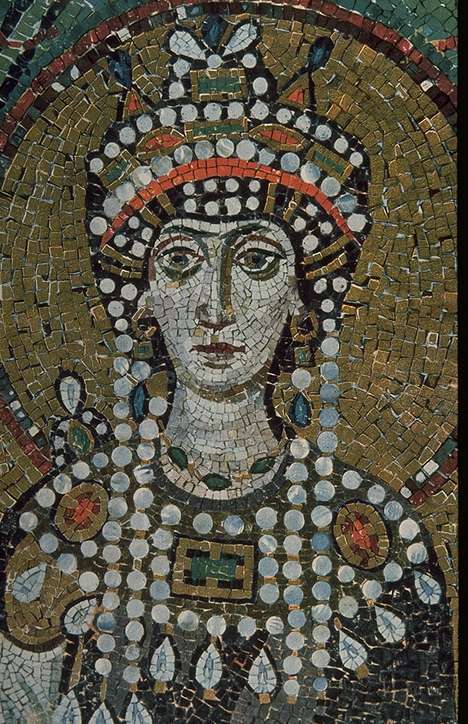

The

Empress Theodora,

Christ

in Majesty,

Moissac – Romanesque art

The statues at

Biblical figures - Chartres

... the question of the temporal nature of art has been almost entirely neglected in contemporary aesthetics ...

‘Metamorphosis is the very life of the work of art in time, one of its specific characteristics.’

Malraux, The Metamorphosis of the Gods, L’Intemporel.

The work’s moment of creation, whatever effect it may then produce, and whatever function it may then perform (which in many cultures may not even be as ‘work of art’) is only a point of departure from which it sets out on a journey of metamorphosis.

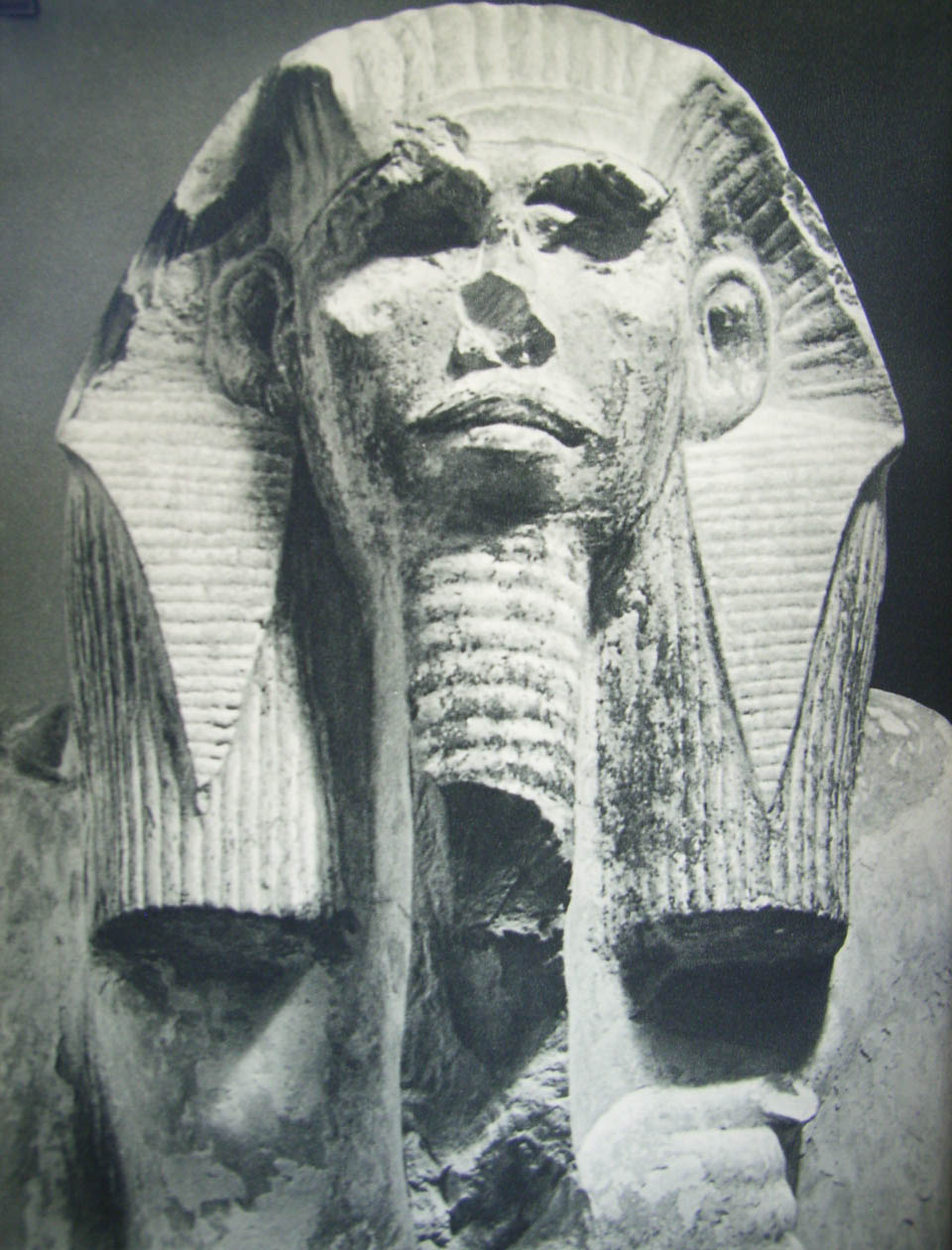

Thus, a work may, for example, begin its life as a sacred object within a particular religious context – a Pharaoh’s ‘double’, for instance, placed in his mortuary chapel to receive the offerings of his subjects. Subsequently, when the beliefs on which that significance depended have perished, the object may recede into obscurity, as did the works of Ancient Egypt for nearly two millennia ... But unlike the mere historical object, it is capable of resurrection, and it returns to life if and when, with the passing of time and its own capacity for metamorphosis, it can re-emerge, but with a significance quite different from that which it originally possessed.

Pharaoh

Djoser – Third

Dynasty

'... if Time cannot permanently silence a work of genius it is not because the work prevails against Time by perpetuating its original language ...'

Malraux - The Voices of Silence

In effect, Malraux’s notion of metamorphosis and dialogue stands traditional thinking about the Renaissance on its head. ‘It is at the call of living forms’, he argues, ‘that dead forms are recalled to life.' ‘In art, the Renaissance produced Antiquity quite as much as Antiquity produced the Renaissance.’

He allows to see why art ‘conquers time’ – why we find (for example) Sumerian religious figures thousands of years old in our art museums (and not just as archaeological artefacts in in history museums); yet at the same time he frees us from having to believe what now seems a manifest absurdity – that art is eternal.

Gudea,

Prince of

... over the course of the past hundred years, and almost as if to mock the inadequacy of our existing explanations, art museums around the world have been filling up with objects whose very presence there poses the problem of the relationship between art and time in an acute and very conspicuous way.

Malraux's account of the temporal nature of art stands out as a landmark achievement in the theory of art. It is no exaggeration to describe his contribution in this area as revolutionary.