This is an English translation of a brief introduction to my book Art and Time prepared for a conference on Malraux in Paris in May 2013.

Version

française

en dessous.

The conference organisers have kindly

asked me to say a few words about my recent book Art

and Time. Rather than speak about the book itself, I

thought I would comment very briefly on the subject it addresses – the

question, so frequently ignored in contemporary aesthetics, of the

relationship

between art and time.

André

Malraux wrote in 1935 that “as well

as being an object a work of art is also an encounter with time”. An

anodyne

comment at first sight, perhaps, but in reality one of crucial

importance. What

exactly does Malraux mean?

Malraux

is not referring to the function

of time within works of art – for

example, the ways in which the passing of time might be represented in

film or

the novel. His subject is something quite different – the external relation between art and time,

that is, the

capacity of works of art to defy the passage of time, their capacity to

survive

across the centuries and millennia – their specific and unique capacity

to transcend time.

Examples

are abundant. The tragedies of Racine

and Corneille are still alive and immediate for us while hundreds of

other plays

written in the seventeenth century are dead and forgotten. Mozart’s

music

speaks to us as if it were composed yesterday while Salieri's seems

covered in a

thick layer of eighteenth-century dust. And while we are very happy to

welcome

the Victory of Samothrace into our

world of art, a simple potsherd of the same epoch would surely be out

of place there.

So

we find ourselves confronted with a

mysterious state of affairs. There seem to be certain human creations

capable

of defying the passage of time – of resisting the unremitting waves of

change

and forgetfulness that engulf all other products of human activity. It

is in

this sense precisely that Malraux says that a work of art is not only

an object

but also “an encounter with time,” because in the work of art we

encounter an

object that possesses a unique power to overcome time – a power to

resist the

ineluctable forces that lead to indifference and oblivion.

Now

in one sense nothing I’m saying here

is new. We are not the first to realize that art possesses a

unique

power to defy time. The Renaissance was intensely conscious of this

power, and poets,

in particular, celebrated it again and again (Shakespeare’s sonnets are

an

obvious example). Moreover,

Renaissance thinkers

went one step further: they also proposed an explanation of the way in which art defies time. Art, the

Renaissance

said, (and the theme is prominent in the poetry of the period)

vanquishes time

because it is “eternal”, “immortal” – entirely unaffected by the

consequences of

the passing of time. Art, in other words, inhabits a world untroubled

by the

passing of time – a world proof against the ephemerality characteristic

of our weak and

vulnerable human lives. Seen in this light, art vanquishes time because

it is

“timeless” – literally outside time.

This

idea was extremely

influential over

the centuries that followed. It underpinned the new discipline

of aesthetics

that emerged in the eighteenth century and still plays a large, if

seldom recognised,

role in the contemporary philosophy of art which, as we know, derives

its key

ideas from Enlightenment thought. And even today

it's not hard to detect the same

idea in our everyday thinking – for example, when

someone describes

an appealing melody as “immortal”, or the publicity blurb for

a novel

tells

us that it addresses “eternal themes”.

But

there’s the rub. Do we today honestly still

believe that art defies time because it is eternal or immortal? As I

argued a

moment ago, we can hardly deny that art does possess a unique capacity

to defy

time; but are we still convinced that it does so because it is

invulnerable to

the consequences of the passing of time – that it is timeless or

eternal? The proposition

strikes us as outdated, does it not – like a remnant from a previous

era? The

poets of the Renaissance and the thinkers of the Enlightenment seem to

have had

no difficulty in accepting the idea, but the world – and especially

the world

of art – has changed enormously since then, and if we are searching for

ideas to

explain the world as we now know

it,

can we continue to accept the claim that art is eternal or immortal?

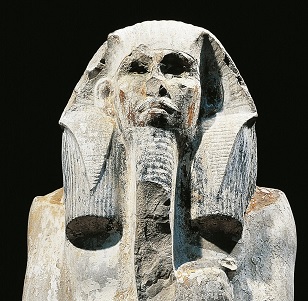

Malraux,

for his part, does not accept it at all. He willingly accepts that art

possesses

a unique power to defy time – and indeed this is a key theme

in the theory

of art expounded in The Voices of Silence and The

Metamorphosis of

the Gods – but he unambiguously rejects the traditional idea

that art transcends

time because it is eternal – that is to say,

unaffected by the passage

of time. Art defies time, Malraux

argues, through a

process of metamorphosis – a

process in

which time plays an essential role, a process in which works such as

the

sculptures on Chartres Cathedral, created at a time in history when the

idea of

art did not exist, can become "works of art" in a culture such as our

own in

which the religious beliefs of the Chartres sculptors have ceased to be

comprehensible.

I do not want, today, to offer a more detailed explanation of Malraux’s idea of metamorphosis. I’ve said almost all I want to say in my two books – especially in Art and Time. I would, however, like to finish with a brief comment on the importance of the idea.

There

are certain commentators who tend to read

Malraux

a little too quickly and claim that his idea of metamorphosis

is in

large measure borrowed from other writers and is not really original.

Nothing

could be further from the truth. The word

“metamorphosis” has, of course, been used by many other writers;

Malraux has no

monopoly on it, or on the general notion of transformation

that it usually signifies.

But in Malraux’s case the idea of metamorphosis takes on a

wholly new

dimension. One is no longer dealing simply with the notion of

transformation. One

is dealing with an entirely new explanation of the relationship between

art and

time – a recognition that the process by

which art

defies time is a process of metamorphosis. This

proposition Malraux borrows

from no one, and one will search in vain to find other authors who use

the word

or the idea in this sense.

It is

difficult to exaggerate the importance of Malraux’s proposition – or

rather his discovery. In an English academic journal I

described

it as “an

intellectual revolution” and I chose those words very deliberately.

This

revolution, I’m well aware, is far from being fully recognised and

understood because contemporary philosophers of art in Anglophone

environments,

as in France, pay very little attention to the temporal dimension of

art. To

borrow Malraux’s words, contemporary philosophers of art seem to

have

forgotten that as well as being an object, art is also an encounter

with time. But this

is to forget one of art's fundamental features, indeed, perhaps

its

most extraordinary – one might even say miraculous – features. Malraux

reminds

us of the crucial the importance of this aspect of art. Art, he

stresses, has a

unique capacity to transcend time. It is, in his words, “the presence in

life of what should belong to death”. But it overcomes time not because it is

eternal

– timeless – but through an endless process of

metamorphosis.

On m’a aimablement invité à vous

dire quelques

mots au sujet de mon livre sorti récemment et portant le titre Art and Time, littéralement

« L’Art

et le temps ». Mais

plutôt que de

parler de mon livre lui-même, j’aimerais évoquer très brièvement la

question

centrale que j’essaie d’examiner dans ces pages – la question trop

souvent

oubliée de la relation entre l’œuvre d’art et le temps.

Il y a quelques

critiques qui ont une tendance à lire Malraux un peu trop vite, et qui

concluent

que son idée de la métamorphose est largement empruntée à d’autres

penseurs et

qu’elle n’est guère originale. Erreur capitale ! Le mot métamorphose a, bien sûr, été

utilisé

assez souvent par d’autres auteurs. Malraux n’a pas de monopole du

vocable, ni de

l’idée générale de transformation qu’il signifie. Mais chez Malraux

l’idée de

la métamorphose prend une dimension tout à fait neuve :

l’enjeu n’est plus

simplement l’idée d’une transformation ; c’est bel et bien une

nouvelle

explication de la relation entre l’art et le temps – une reconnaissance

que le

processus par lequel l’art défie le temps est précisément un processus

de

métamorphose. Cela

Malraux ne l’emprunte

nulle part, et on chercherait en vain d’autres auteurs qui auraient

utilisé le

mot ou l’idée dans ce sens-là.

Il

est difficile d’exagérer l’importance de cette

proposition – ou plutôt de cette découverte. Dans un article d’une

revue

anglaise, je l’ai appelé « une révolution

intellectuelle » et

j’ai

choisi ces mots très délibérément. La révolution en question, j’en suis

très conscient,

n’a pas encore été pleinement reconnue parce que la philosophie contemporaine

de

l’art dans les pays anglo-saxons, comme en France, prête très peu

d’attention

à la

dimension temporelle de l’art. Pour reprendre les mots de Malraux, la

philosophie contemporaine

de

l’art semble avoir oublié que l’art n’est

pas

uniquement un objet mais aussi une rencontre avec le temps. Mais c’est

oublier une des caractéristiques fondamentales de l’art – voire sa

caractéristique la

plus extraordinaire, pour ne pas dire miraculeuse. Malraux souligne

l’importance capitale de cet aspect de l’art. L’art, maintient-il,

possède une capacité

unique de transcender le temps. C’est, écrit-il « la présence,

dans la

vie, de ce qui devrait appartenir à la mort ». Mais l’art ne

vainc

pas le

temps parce qu’il est éternel - « timeless » - mais par un processus, sans fin,

de

métamorphose.