PARDON ME, BUT YOUR SHURIKEN IS IN MY NECK: the phenomenon in Japan

The Samurai or Onmitsu kenshi ('spy swordsman') - to give its Japanese title - was made by Senkōsha Productions, the television-production arm of the Senkōsha Company, a big advertising agency based in Tokyo which still exists though it has long since closed its television side.

Senkōsha Productions had produced Japan's first home-grown children's TV series, Gekkō kamen ['Moonlight mask'] for KRT (later TBS) which began screening daily in 10 minute episodes. As its popularity grew, it became a weekly series with half-hour episodes. It began in February 1958 and ran until July 1959, its ratings going as high as 60% in 1959. It was about a mysterious superhero in a white mask, sunglasses and turban who rode around on a motor bike, created by Kawauchi Yasunori and originally serialised in the comic-book, Shōnen kurabu. It was also made into a feature film by Tōei, starring Omura Fumitake. Producer Nishimura Shunichi claimed to have wanted to make a jidaigeki (historical drama) but didn't have the budget so made this instead..

What makes this TV series of especial interest is that it was directed by Funatoko Sadao who also directed The Samurai and it starred Ōse Kōichi who was to play Shintarō later. Despite the fact his face was hidden by a mask and his identity kept secret to preserve the mystery, Gekkō kamen made a star of Ōse. Unfortunately, the show's popularity with children backfired a bit because there were numerous incidents of children jumping off roofs and trees in emulation of their hero and injuring themselves. This became a real problem as did cases of children suffocating through wearing the toy mask that was part of the merchandising. This sort of thing may have led to its cancellation. "Gekkō kamen" seems to have been one of those nauseatingly good guys only 50s TV could produce with his injunction: "Do not hate. Do not kill. Let's be forgiving."

Ōse got the part of "Gekkō kamen" when Nishimura Shunichi went to the Tōei movie lot and picked him from some photographs, then interviewed him on the spot. At the time there were three candidates for the part. However, the actor needed to have clear cut features which would be easy to draw so Ōse was chosen. He took one character from Kawauchi Yasunori's given name and incorporated it in his stage name in recognition of the boost to his career this role gave him.

Nishimura, born in 1928, had transferred to Senkōsha from another company at the request of the head, Kobayashi Toshio, in 1957. He not only produced Gekkō kamen but Jagā no me, Kaiketsu Harimao, Kyōfu no miira, The Samurai, and Yūsei no ōji ['Prince Planet'].

Senkōsha Productions followed this up with another children's TV series, also directed by Funatoko and starring Ōse, entitled, Jagā no me ['Eye of the jaguar'], set in Hong Kong and Kowloon. It was based on a pre-war adventure novel serialised in Shōnen kurabu. It was shown at 7pm Sundays (the timeslot later occupied by The Samurai and previously occupied by Gekkō kamen). It finished in March 1960.

Kaiketsu no Harimao ['Wonderman Harimao'] is also of interest because, again, it was directed by Funatoko and it starred Katsuki Toshiyuki who was to play two major villains in The Samurai, Kiba Jinjūrō and Momochi Genkurō. Maki Fuyukichi who was to play Tonbei had a role as a gangster boss, Captain KK. This series was on an even bigger scale than Jagā no me as it was set in Indonesia, the Arafura Sea and other parts of Southeast Asia and it used overseas locations. "Harimao" (Malay for 'Tiger'), the hero played by Katsuki, was dressed in sunglasses, turban and a sort of Sinbad-style costume with a studded leather belt with a tiger's head buckle. This character, a former Japanese naval officer named Otomo Michio, helped people oppressed by their governments and fought secret societies and drug dealers. The series began broadcasting weekly on NTV in April 1960.

The Samurai was Senkōsha Productions first period piece. Nishimura had been raised on the magazine, Kōdan kurabu and loved period pieces. After Jagā no me he felt the time was ripe. He wanted to do Kurama Tengū with Ōse but nothing came of it. ('Kurama Tengū' a black-garbed, pistol-packing swordsman on a white horse, hero of a string of novels by Osaragi Jirō set in the late Tokugawa perod, i.e.,mid-19th century, is a perennial subject for films and TV series, going back to the silent era. Some of Japan's greatest swordplay stars such as Arashi Kanjūrō have played the part). Ōse eventually did Kurama Tengū for Mainichi TV from February to July 1967.

At the time Nishimura was given the OK to do The Samurai, he was given a budget of Y1,000,000. Even then the cost of a 30 minute TV series was ten times that. Nishimura was also extremely short staffed. He not only was the producer but carried the camera equipment to the locations. He even handled the scripts as he lived with planning chief Igami Masaru who did the scripts as a 'domestic industry' and he also worked under Igami as a planner. He and his cohorts regarded themselves as amateurs and The Samurai as simply a children's period piece and were not too worried about historical accuracy. They shamelessly took their ideas from whatever ninja or swordsman novels they could lay their hands on. They took their books even on location and if someone found a good idea even there, it would straightaway be incorporated in the script.

Originally it was planned to do The Samurai in four series with a different hero in each. The name of the hero of each story would be drawn from a combination of the names of the four seasons plus the words 'mountain', 'river',' grass' and 'tree'. Because the series would start in autumn, the hero's name would be Akikusa Shintarō [literally 'Autumn-grass Shintarō']. In spring the hero would be called Haruyama ['Spring-mountain'l, in summer Natsuki ['Summer-tree'] and in winter, presumably, Fuyukawa ['Winter-river']. But because the name and character of Akikusa became so well known and popular, it stuck and the hero remained the same for the whole 128 episodes that were eventually made.

One film series which seems to me to have influenced The Samurai, at least superficially, is the 'Shingo' series, starring Ōkawa Hashizō. This was about a young samurai, who, like Shintarō, was an illegitimate son of a shogun and went round righting wrongs in the guise of a rōnin. These films were made by Tōei between 1959 and 1964,of which 6 predate The Samurai by a couple of years. Moreover, not only are the heroes' origins similar but their names (Aoi Shingo and Akikusa Shintarō) and also their hairstyles (ponytails) and cast of features (though Ōkawa is even better looking).

The Samurai was broadcast in Japan on TBS on Sundays from 7pm to 7.30pm. Curiously, it was followed by Popeye (7.30-8pm). It was billed as a 'television movie' though it was actually a children's TV series. Like most Japanese programs made at that time it was in black and white. It started on 7th October 1962 and ran every Sunday, with only two exceptions during 1964 when it was pre-empted for the Olympic Games, until 28th March 1965. It was replaced by The New Samurai (Shin onmitsu kenshi) in the same timeslot on 4th April 1965 until 26th December 1965.

Each story in the programme was told in 13 half-hour episodes (with the exception of Puppet Ninja which was cut short because of the Olympics). Each block of episodes making up a story had its own distinctive title.

The first story, Spy Swordsman, was written by Katō Yasushi, who had been Funatoko's mentor in the film industry. It introduced us to Akikusa Shintarō as the older half-brother of shogun Ienari, wearing formal dress of hakama and kataginu, his hair not in its usual ponytail but in a topknot and his head half-shaven. The year is 1792 and the shogunate wants Ezo (Hokkaido) investigated as to its resources. There have been problems with Russia casting its eye on it. (Adam Laxman had just returned some castaway Japanese fishermen from Russia). Not only that, there are reports of corruption and piracy up north as well. Matsudaira Sadanobu, the chief councillor, embarking on his fiscal reforms, is considering transferring the lord of that fief (Matsumae) elsewhere. So he despatches Shintaro north to look into things as Shintaro has decided to renounce any claim to power and a life of ease and devote himself, in the guise of a rōnin living among the ordinary people, to ferreting out plots against Ienari and generally protecting his interests. Sadanobu also has Ienari's interests at heart. Thus when we next see Shintarō, he is in the dress of a rōnin - simple kimono and hakama (though costly white-hilted swords) and a full head of hair in a ponytail.

Neither Tonbei nor Shūsaku appear in this. There are no ninja at all. Shintarō's chief adversary is the ambitious and rather overzealous retainer of the Lord of Matsumae, Kiba Jinjūrō, who resents Shintarō's presence as a spy from Edo, seeing it as a threat to his lord. Here the series captures well the resentment toward shogunate spies (who proliferated under Sadanobu).. Nonetheless, Ōmori Shunsuke (who played Shūsaku) had a small role as a child (coincidentally also called Shūsaku) while three future ninja also had parts - Kiba was played by Katsuki Toshiyuki ("Genkurō"); an Ainu rebel leader was played by Maki Fuyukichi ("Tonbei") and there was a blind master swordsman now a rōnin in one episode and a gangster's master swordsman bodyguard in another played by Amatsu Bin ("Fūma Kotarō, Kongō of Kōga, Gensai the Wolf,"et al.).

This story is rather an oddball affair as it seems the producers went rather overboard on the 'frontier' look of 18th century Hokkaido with the Ainu playing Indians and the Japanese playing white settlers. There were lots of riding around on horseback and firing of muskets and in many episodes Shintaro even brandishes an anachronistic six-gun! (Probably Nishimura's attempt at a Clayton's Kurama Tengū). However, it is an interesting attempt to depict the tensions between Japanese and the Ainu who are being displaced, the difficulties of colonists living so far from home, the poverty of many Japanese villagers and so on. Not all Ainu are good and noble - one is a notorious smuggler and bandit. Not all the Japanese are oppressive and racist. Many have Ainu friends and help them. Kiba, an official, is just and fair, even kind in his dealings with both Ainu and Japanese, even though he is the ostensible villain, being after Shintarō. There was a rather poignant scene where Shintarō encounters Ichi, a former geisha he knew in Edo, at an inn and they exchange reminiscences and wonder what each is doing in such a place. Shintarō wasn't always right in his actions. In one episode he rather irresponsibly left a bandit with a village ill-equipped to hold such a person and people died because of it. Another difference in him was he was not yet in the habit of going round lecturing people, he did not tell a brother and sister to give up ideas of taking revenge and go home and raise families. Instead he gave them advice on how to accomplish it and abetted them by stealing a sword. The story was unlike those that followed, being a series of loosely connected episodes with no strong over-arching plot other than Shintarō's mission to collection data on Ezo. Even the theme song was different from the later series being a jolly song sung by a children's choir. The song used as the main theme in later stories occurs only in the middle of some of the episodes.

Children's TV jidaigeki were not very popular at that time as foreign 60 minute series like The Untouchables, Ben Casey, Laramie et al. and foreign cartoon movies were what attracted Japanese children. The Samurai looked like being just another children's series despite the casting of the popular Ōse as the hero and, opposite him, as his chief rival, the popular star of Kaiketsu Harimao, Katsuki Toshiyuki. It was Ōse's first jidaigeki and at first he didn't handle the sword well. He raised blood blisters on his hands but declared he would continue to do so until he became a high-grade sword-wielder. It was not particularly well received. Indeed, this story was not bought by Australian TV until much later, after all the other stories in the series had been repeated three times.

However, the second story, Koga Ninjas, introduced the missing and magic ingredient lacking in the first story - ninja. Just as in Dr.Who where the Daleks' introduction sealed its popularity and the direction it would take, so it was with The Samurai with the ninja. The ratings took off like the proverbial rocket and its popularity soared. Thereafter, The Samurai became the ninja TV series par excellence.

The reason for this was simple. Japan was in the grip of the ninja 'boom'. "Ninja" had been popular figures on or off for most of the century but in the post-war period this particular boom began in the publishing world in 1958 with Yamada Fūtarō's novel Kōga ninpōchō. (This was finally turned into a film in 2002 with Shinobi. Yamada went on to make quite a name for himself with a whole library of ninja novels throughout the 60s and 70s which got progressively sexier. A number of films were based on them). The following year Shibata Renzaburō's novel, Akai kageboshi and Shiba Ryōtarō's Fukuro no shiro ['Owl castle'] appeared. Both were later made into films. Around the same time Shirato Sanpei's 17 volume comic-strip series, Ninja bugeichō, was published by Sanyōsha and took three years to complete. It depicted a peasant revolt led by a group of ninja against a feudal lord. As this was the time of the student and left-wing protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty (Anpo),the work was well received.

In the children's magazine, Shōnen Sunday, a ninja comic series by Yokoyama Mitsuteru, Iga no Kagemaru was serialised from April 1961. This story was followed by university students and this boosted the genre's popularity in the mass media.

Then a novel by Maruyama Kazuyoshi, Shinobi no mono, which had been serialised in the Sunday edition of the left-wing newspaper, Akahata (circulation 700,000),was published as a monograph and went through many printings. It depicted Ishikawa Goemon (a famous brigand who was boiled alive at the end of the 16th century by order of Hideyoshi) as a ninja (which he may or may not have been) who fought against warlords of the civil war period, together with the farmers.

Daiei made a film based on it starring Ichikawa Raizō which was a tremendous hit as, for the first time, ninja were presented realistically and in detail. Prior to that film ninja tended to be quasi-supernatural creatures given to turning into toads or hurling thunderbolts at opponents. The film spawned a number of sequels and a TV series and is generally credited with starting the ninja-boom in films and television. It was released on 1st December 1962, five weeks before the first episode of The Samurai's Koga Ninjas was broadcast. The film's sequel, Zoku Shinobi no mono, was released 10th August 1963, a third film, Shin Shinobi no mono on 28th Dec. 1963; Kirigakure Saizō on 11th July 1964; a 5th Zoku Kirigakure Saizō on 30th December 1964; the 6th Iga yashiki on 12th June 1965; the 7th Shin Kirigakure Saizō on 12th February 1966 and the 8th Shinsho Shinobi no mono on 10th December 1966. All of them were in black and white, all set in the civil war period, all starred Ichikawa Raizō in various ninja roles and all were big money-makers for Daiei.

Their tone was rather sombre dealing with betrayal, assassination and dark doings yet they depicted and brought out the underlying humanity of these cold-blooded killers. Too, the ninja were often seen in opposition to the powers of the day and the cruelty of the ruling classes to the peasantry. So there was a certain left-wing element in them which appealed to students in their own struggles. This was, after all, the time of the Vietnam War and, although Japan wasn't involved in it as Australia was, the papers still carried the sort of headlines all too familiar to Australians of the same generation. So the guerrilla tactics of the ninja also struck a chord. Of course, their special skill and acrobatic ability appealed, too. The ninja characters of these Shinobi no mono films were often drawn from the Tachikawa Bunko novels published in Osaka at the beginning of the century whose characters had passed into popular consciousness so that they seemed like real historical figures even when they were not - characters such as Sarutobi Sasuke, Kirigakure Saizō and so on.

Tōei also started a series of ninja films, in March 1963 which ran until January 1968. Unlike Daiei's these did not have a regular cast of actors. Most of them were based on the works of Yamada Fūtarō. Some were animations based on Shirato Sanpei's works, of which the best known is the 1966 film, Watari, scripted and directed by the team from The Samurai. It was a live action film with lots of special effects and included Maki "Tonbei" Fuyukichi in its cast.

Some of Daiei's and Tōei's ninja films spawned TV series. There was the animation series, Shōnen ninja Kaze no Fujimaru, which began in 1963 and Shinobi no mono which began in mid-1964 (oddly made by Tōei and not Daiei for NET). In addition, there was Fuun Sanada-jō (TBS, 1964), Rokunin no onmitsu (NET, 1964), Iga no Kagemaru (TBS, 1964), Yagyū Bugeichō (NET, 1965), Kamen no ninja Akakage (Fuji,1967, which had Maki and Amatsu in it), O-niwa-ban (NTV, 1968) and the best known out here apart from The Samurai, Ninja Butai Gekkō (Phantom Agents) (Fuji TV, 1964-1966). If one was to go by the newspapers alone, the ninja craze really peaked in 1964. There seemed to be endless references to TV programs, films and books about them, not all of them fiction. A few TV documentaries featured living practitioners of the art like Hatsumi Masaaki, 34th Grandmaster of the Togukure-ryū, who'd been strutting his stuff in the mass media since the early 60s. Ironically, The Samurai featured at least two Togakure ninja long before it became megatrendy.

However, it is The Samurai that is remembered today in Japan. It always scored high in the Japanese TV ratings and even today books and articles discussing Japanese TV programs or TV samurai and/or ninja programs, or even articles about ninja, single it out for special mention as a kind of milestone in TV programs or as a type or byword of its kind. It was probably the first children's TV series to use ninja on a regular basis and this became its trademark. It was also one of the major popularisers of ninja in the mass consciousness. Children (and others) were attracted to it by its fast pace, its special visual and sound effects and camera tricks to duplicate ninja skills. The ninja equipment also fascinated. Adults enjoyed it, too, which increased its popularity.

Another of its trademarks was the dynamic and unusual photographic angles, particularly the dramatic use of close-ups. This, too, was remarked on in Japanese books as well as out here. A typical example is one sequence involving a master ninja where he is standing alone in a room near a hanging scroll with calligraphy on it, having made a momentous decision and is now left with his thoughts. The camera zooms in on his face so it fills the screen, there is a cut, then it zooms in again to his right profile, then his left, then the back of his head - in short he is shown from all angles in sudden close-up to underscore the moment.

So popular was the series, it was exported in an English version to Hong Kong, Southeast Asia and Australia where it enjoyed the same incredible popularity. The English version was dubbed by various small dubbing companies such as George S. Reid. William Ross who dubbed Shintarō and later Shinnosuke worked for many of these, eventually forming his own, Frontier Enterprises, in 1964. Ross was born in Cincinnati in 1923 and went to Japan to learn Japanese in the early 1950s with the intention of joining the U.S. State Department. However, he became involved with the Japanese film industry and appeared in over 80 films and had regular roles in several TV series. He got into the dubbing side of things in 1959 where he proved to have such a real flair for working with the other dubbing actors, he soon became a director. He has worked for all the major Japanese films studios, dubbing over 400 live action and animated feature films and many, many Japanese TV series not only dubbing but as dialogue writer, dubbing director and voice actor. He was an associate producer on Tōei's Terror Beneath the Sea and The Green Slime (but we won't hold that against him). He continued to act and appeared as the pilot in Message from Space (and also in Bushido Blade which also had Amatsus Bin in it). For the dubbing of Japanese films and TV series, he was forced to use whatever English-speakers he could find rather than trained actors - businessmen students, musicians, etc. with little or nor acting experience. He did hold auditions and tried to get the best he could and train them thoroughly.

The landmark second story not only introduced ninja in the form of 13 Koga ninja after a secret treasure of Takeda Shingen's, it also introduced Baba Shūsaku, Shintarō's young companion. As mentioned earlier, Shūsaku, then about 8 years old, was looking for his father who had been kidnapped by the Kōga, and Shintarō decided to help him He had a pet monkey with whom he was briefly reunited when they reached his home in the mountains. Shintarō was joined for a short time by a renegade Kōga ninja who was supposed to spy on him and kill him but deserted because of Shintarō's kindness to him. Shūsaku was returned to his father when Shintarō freed him and others from the Kōga's clutches.

The third story, Iga Ninjas, featured 10 Iga ninja, led by Momochi Genkurō, a descendant of that most famous Iga ninja, Momochi Sandayū. They were involved in a plot of the Lord of Owari to kill Matsudaira Sadanobu. This was the story that introduced Tonbei. He was sent from Edo with a group of the shogun's Iga ninja to help Shintarō. Until his appearance in The Samurai, Maki Fuyukichi had only played villains. He had been a gymnastics champion at school and thought he could use this to play a ninja. He was said to have fumbled the swordplay scenes but somehow concealed it. Nishimura claims that these days everyone does the ninja's downward cut but they were the first to invent it. They didn't have a stuntman. Once an arrow cut Maki's face and wounded him badly but he spent the evening resting quietly. He was young and tough and truly seemed like a ninja, or so says Nishimura. This one did not feature Shūsaku.

The fourth story, Black Ninjas, featured Genkurō's former second in command, Gensai the Wolf, now working with a group of Kōga Ninja calling themselves Black Ninja who were employed by the Retired Lord of Owari to collect the signatures of the various domain lords on an agreement to bring down the current shogun and install the lord in his place . The fifth, Fuma Ninja and sixth, Fuma Ninja Continued, featured the Fūma ninja under Fūma Kotarō Kaneyoshi and his sister, Oboro, after a treasure buried by the Hōjō family. The seventh, Ninja Terror, featured Kishū and Negoro (inexplicably called 'Negishi' in the English version) ninja in conflict with each other at the time of the succession of the new young lord to Kii fief. The eighth, Phantom Ninja, had a group of seven Maboroshi or Phantom Ninja, under Kongō of Kōga, employed by the Lord Rokkaku to bring about the downfall of Matsudaira Sadanobu. The ninth, Puppet Ninja, featured Puppet Ninja and smuggling and another attempt to bring down the shogunate. The tenth, Contest of Death, was a virtual ninja all-star with ninja of various schools being featured in each episode trying to kill Shintarō as part of Kongō's plan to keep the ninja from becoming extinct by setting up a contest (the aim of which was to kill Shintarō) the winner(s) to be employed by feudal lords who would then be manipulated into starting a civil war. In many of the stories the individual episodes focused on a particular ninja and a particular skill so the program was a real showcase for ninja talent.

Of the stories, the ones which seemed to have left the most lasting impression are the two about the Fūma ninja. This was because the scriptwriters really hit their stride and threw in a lot of unusual ninja devices, particularly explosives, underwater "dragon ships", an elaborate plot that took two 13 part stories to tell, involving maps, mirrors, secret locations, mystery, a wide range of locations, both coastal and inland, mountain, forest, volcanic and urban. A big strength was the chief villain, Fūma Kotarō, as played by Amatsu Bin, a tall, hawk-faced actor with large glittering dark eyes, a deep, sepulchral voice, and a tremendously menacing presence. This role propelled him into a career in films and TV playing villains, first in ninja films, then yakuza films, mainly for Tōei. One writer said that his voice 'resounded with images of the dark ninja lifestyle'. He was a good match and a foil for the noble Shintarō. The Fūma ninja were looked on as the most terrifying of Shintarō's opponents. Kotarō was certainly the most witch-like.

Another story which has been singled out for mention is Phantom Ninja. This time the chief villain was a "super-ninja" with the title Kongō of Kōga, but still played by Amatsu Bin. Each ninja in the group had some special skill such as Chidori's 'Blinding Snow' trick in which she disappears by throwing blossoms in the faces of her enemies or Kongō's almost teleport-like trick of nearly being in two places at once and his skill at impersonation.

Of course, the TV series (as well as the ninja films) had the usual effect on the gullible. On the night of 21st August 1963, a 16 year old boy dressed himself in a home-made ninja outfit, equipped himself with the traditional seven weapons and tools ninja carried and attempted to break into the Imperial Palace in Kyoto to test his technique against the heavy police guard. Needless to say he was arrested.

The scripts were written by Igami Masaru or Katō Yasushi. The episodes were directed by Funatoko Sadao or Toyama Tōru and the music was chiefly by Ogawa Hirooki. The fight arranger was Matsumiya Takehisa. Quite a little stock company of players was built up, apart from the three regulars. Amatsu Bin not only played Fūma Kotarō in both parts of Fuma Ninja, and Kongō of Kōga in Phantom Ninja, Puppet Ninja and Contest of Death but also Genzō the Spider in Koga Ninjas, Gensai the Wolf in Iga Ninjas and Black Ninjas. He also had two different roles in Spy Swordsman, a sympathetic blind rōnin and a villainous master swordsman, so appeared in all but one. Katsuki Toshiyuki appeared twice but was not used again after his appearance as Genkurō. One can only speculate why not. Perhaps he didn't fit the type needed for the show as well as Amatsu. Stalwart of many samurai films, Yoshida Yoshio played Garyūdōshi, head of the Negoro ninja while singer Saga Naoko played Oboro, Fūma Kotarō's sister.

Of the main people associated with the series, Ōse quit acting in 1969, in the belief that an actor should always retire at his peak. He set up a successful company dealing in entertainment promotion and property in 1971(it has a multi-million dollar building in western Tokyo, runs several commercial buildings, a golf course and a chain of noodle shops, the last being established in 1980). Ōmori Shunsuke ("Shūsaku") also left acting, soon after the show finished. He is now working for a construction company in Tokyo Director Funatoko and villains Amatsu Bin and Yoshida Yoshio are also dead, Funatoko in 1972, Amatsu in 1979 and Yoshida in 1986. Maki continued in films until relatively recently. He died in 1998.

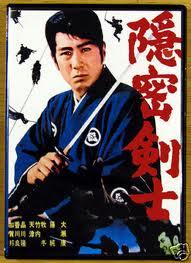

In March 1964 a feature film made by Tōei based on the TV series was released. Like the series, it was called simply, Onmitsu kenshi. The director was Funatoko, the script by Igami, the music by Ogawa and it had most of the original cast of the TV series with one notable exception. Shūsaku was played by Takeuchi Mitsuru not

Ōmori Shunsuke. Amatsu Bin played the chief villain, Kōga Ryūshirō, and a young Fuji Junko played his sister. It concerned a group of feudal lords who had signed a compact to overthrow the shogun, lead by the Lord of Owari.

It was loosely based on the fourth story with bits of business from the

third story and the villain's name taken from the second story and the fact he

had a sister echoing the Fuma Ninja stories..

In March 1964 a feature film made by Tōei based on the TV series was released. Like the series, it was called simply, Onmitsu kenshi. The director was Funatoko, the script by Igami, the music by Ogawa and it had most of the original cast of the TV series with one notable exception. Shūsaku was played by Takeuchi Mitsuru not

Ōmori Shunsuke. Amatsu Bin played the chief villain, Kōga Ryūshirō, and a young Fuji Junko played his sister. It concerned a group of feudal lords who had signed a compact to overthrow the shogun, lead by the Lord of Owari.

It was loosely based on the fourth story with bits of business from the

third story and the villain's name taken from the second story and the fact he

had a sister echoing the Fuma Ninja stories..

In August 1964 a second feature film was released by Tōei, this one called Zoku Onmitsu kenshi, also directed by Funatoko and scripted by Igami. This one did have all the original cast including Ōmori. It seems to have been loosely based on the Fūma stories. Saga Naoko and Amatsu Bin were also in it. It was about the search for a buried treasure in seven gold-mines in Izu, the location of which was recorded on three mirrors (Water-god, Wind-god and Fire-god were the names of the mirrors). It involved the Fūma ninja, the Tokugawa family and the Iga group.

A stage version of The Samurai was produced at the Shōchiku Kokusai Gekijō (a well-known theatre in the Asakusa district of Tokyo which closed in the early 1970s), though I haven't been able to discover which year. Ose had his own stage show with a popular singer, Hatakeyama Midori, in early May 1964 at the same theatre.

By the time the series finished at the end of March 1965, it had become a bit stereotyped and had lost some of its popularity. To overcome this, a new series starring Hayashi Shinichirō as a samurai/ninja (best of both worlds?) named Kage Shinnosuke, the head of the Kage ['Shadow'] ninja, with a regular female character, Kanae, played by former child star, Shiratori Mizue, was devised. This was The New Samurai (Shin Onmitsu kenshi). Maki Fuyukichi continued as Tonbei and a new boy character, Daisaku, played by Ninomiya Hideki, was also introduced. This series was originally set on the southern island of Kyushu unlike the original series which, with the exception of the first story, had been set on the main island of Honshū and central Honshū at that. This was appropriate as the Satsuma fief, in the south of Kyūshū where most of the first story of the new series was set, was a turbulent place, known for its network of spies and its hostility to the shogunate. The fictitious Kage ninja were based on Kyūshū's Kikuchi ninja who were sent to investigate the land and industries of the area. Like the original series, use was made of location shooting as well as studio work. For this the makers, in consultation with the actors, came up with new forms of ninjutsu and ninja weaponry to appeal to the viewers. The new series continued in the same timeslot as the original series, Sunday 7-7.30pm on TBS and was also sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Amatsu Bin also appeared as a villain in this.

However, by this time the ninja boom had peaked and the series was cancelled in December 1965 after only 39 episodes (the original series had 128). It was remarked that Maki Fuyukichi was more popular than the star, Hayashi Shinichirō, who hasn't been heard of since. The series was succeeded on TBS in that timeslot in January 1966 by a ghost cartoon, Ultra Q, as the ghost and monster boom had begun. Also the American spy craze and The Man From Uncle were all the rage.

In the meantime, Senkōsha Productions had set out to capture an adult audience. In October 1965 their production of Tange Sazen, starring Nakamura Takeya, appeared on Wednesday nights at 9pm. The team from The Samurai were on the job again - the script was by Igami Masaru, the director was Funatoko Sadao and the producer was Nishimura Shunichi. ("Tange Sazen" was another Japanese perennial, a nihilistic one-eyed swordsman who has been the subject of countless films and TV series, though he originated in literature). However, the expected high ratings did not eventuate and it was cancelled after two stories in March 1966. Shortly afterwards, Senkōsha Productions disbanded (this was probably where the reports in Australia originated that Senkōsha had gone bankrupt). The staff transferred to other TV production companies.

Ninja TV series never quite disappeared entirely from Japanese TV. There was usually at least one series with ninja or Tokugawa spies and anything about the Yagyū family would be sure to feature them. Of the later ninja series, one interesting one was Yaji Kita onmitsu dōchū (NTV, 1971) which postulated that the two roguish vagabond heroes of the early 19th century novel, Dōchū hizakurige, Yaji and Kita, were actually government spies. It was directed by Funatoko Sadao. In 1972 there were several ninja shows: Nekketsu Sarutobi Sasuke, starring Sakuraki Kenichi, a half hour series on TBS each story complete in one episode; Ninpō kagerō-giri, an hourly series on Kansai TV, starring Watase Tetsuya and Watase Tsunehiko and based on a work by Saotome Mitsugu. In 1980 there was Kage no gundan which led to a feature film the same year, Kage no gundan: Hattori Hanzō (there was another ninja film that year from Tōei, Ninja bugeichō: Momochi Sandayū, starring Sanada Hiroyuki and Chiba Shinichi).

In October 1973, The Samurai was revived as a new series starring Ogishima Shinichi as Matsudaira Shintarō Nobukatsu. By this time Funatoko Sadao had died (in February 1972) so the former assistant director of the old series, Kikuchi Akira, directed it. It was made in conjunction with Tōei and Takeda Pharmaceuticals were again the sponsor. Maki Fuyukichi was also in it as was Amatsu Bin but otherwise the cast was new.

It began in The Samurai's old timeslot of Sunday 7-7.30pm on TBS on 7th October 1973 under the title Onmitsu kenshi. It featured the usual regular female and boy companions while Amatsu Bin played the chief ninja villain in the first story. In all ways it seemed to have tried to follow the original, even down to the style of naming the episodes. Ogishima wore the same ponytail hairstyle as Ōse. However, the ratings were not impressive, so for the second story the producers seem to have gone a bit bonkers, throwing in everything but the Starship Enterprise so that what emerged must have been more like a parody or travesty of the original Samurai to judge from the episode titles. It was renamed Onmitsu kenshi: tsuppashire! ("Run swiftly. spy swordsman!") and pitted the hero against dragons, evil gods, ghosts, human bombs, airships, fire demons and so forth. In each episode, too, popular singers appeared as guests in an attempt to boost ratings. Not surprisingly it was cancelled after 26 episodes, the last being shown on 31st March 1974. This was during the height of the animation craze - Mazinga, Gatchaman (Battle of the Planets), etc. One writer commented that probably the day of The Samurai had passed.

However, it was never completely forgotten. In 1979 King Records released a

soundtrack LP of the original series, simply entitled Onmitsu Kenshi, no.

3 in their Natsukashii shōnen eiga meisaku

gekijō series.

This

consisted of the various songs, the opening theme of the 10th story, sound

effects of shuriken and smoke bombs, and extracts from some of the episodes on

one side and on the other a condensed version of the 2nd Fuma ninja story,

narrated by Ōse. Within there is a full

listing of all the episodes plus cast and crew, an interview with producer

Nishimura Shunichi and lots of photographs.

During the 1980s a number of books about TV series of yesteryear or the history of television or crazes included chapters on it. Also there was a cinema in Tokyo in the early 80s which screened all 128 episodes back to back in an all-night marathon. Around 2000, a video was released with the first episode ("Man From Edo") and the last episode, ("The Duel") bracketing an episode from the middle ("The Stolen Case" ). These were, of course, in Japanese. More recently the whole series has been released to DVD in a boxed set. Of course these are in Japanese and not dubbed.

For the show's 50th anniversary in 2012, Potto Shuppan published a book,

Onmitsu kenshi ima koko ni yomigaeru! by Tokunaga Fumikazu (ISBN

9784780801859 - the title means something like The Samurai lives again

here).

It

is divided into three major sections. The first discusses Koga Ninja, the

second, Iga Ninja and the third Fuma Ninja. Each section is

prefaced with photos from the story, including some behind-the-scenes shots. The

discussion includes historical background, background to the making of the

story, plot synopsis, ninja weaponry (Banshenshūkai

is cited in the bibliography). where it was shot, and so on.

Also as part of the 50th anniversary, all 128 episodes were re-released in three box-sets the same year.

[The Phenomenon in Australia] [Gone But Not Forgotten: 1980s to present] [Cast & Characters] [New Samurai] [1973 Revival] [Historical Characters Mentioned in the Samurai] [Australian Press Articles] [Phantom Agents] [Episode guide - Man From Edo] [Episode guide - Koga Ninja] [Episode guide - Iga Ninja] [Episode guide - Black Ninja] [Episode guide - Fuma Ninja] [Episode guide - Fuma Ninja Continued] [Episode guide - Ninja Terror] [Episode guide - Phantom Ninja] [Episode guide - Puppet Ninja] [Episode guide - Contest of Death] [Introduction] [Historical background] [Ruth Manley] [Home]