Why

art is never representation (even

when it

represents)

This

is a slightly edited version of a paper I

delivered a conference at the Australian National University in

December 2017.

The images are from the PowerPoint presentation that accompanied the

paper.

The

question of whether or not art is essentially a representation of

reality has

long been a bone of contention among philosophers of art – especially

in the

major branch of that discipline called the analytic philosophy of art,

or

analytic aesthetics. Some philosophers are convinced that art is essentially representation, although

as you can imagine, they’re forced to resort to some rather tortuous

reasoning

when it comes to music or non-figurative visual art, both of which on

the face

of it don’t usually seem to represent anything in any normal sense of

the word.

Other philosophers of art, apparently struggling for a compromise

solution, argue

that while literature and visual art are essentially representative

arts, music

is not – a move that, unhappily, simply begs a basic question: if, as

the

proposition suggests, there are both “representative arts” and

“non-representative” arts, what do they have in common, fundamentally,

that

authorises us to call them both “art”? So, we are back to square one:

What is

the nature of art? Is it essentially representation? Or

something else?

I don’t

want to lead you down the highways and byways of these debates. They’ve

been

going on, more or less fruitlessly, for decades now and are, in my

view, among

the more tedious and arid areas of analytic aesthetics which, at the

best of

times, tends, regrettably, to be a rather tedious and arid affair

anyway. Yet I

suppose we do have to admit one thing. There is a tendency for many of

us to

assume, more or less unthinkingly, that art – especially visual art and

literature – does somehow, in some ill-defined way, “represent the

world”. We

struggle to apply the proposition to art forms such as music of course

– with

the doubtful exception of so-called program music – but it’s

nonetheless hard

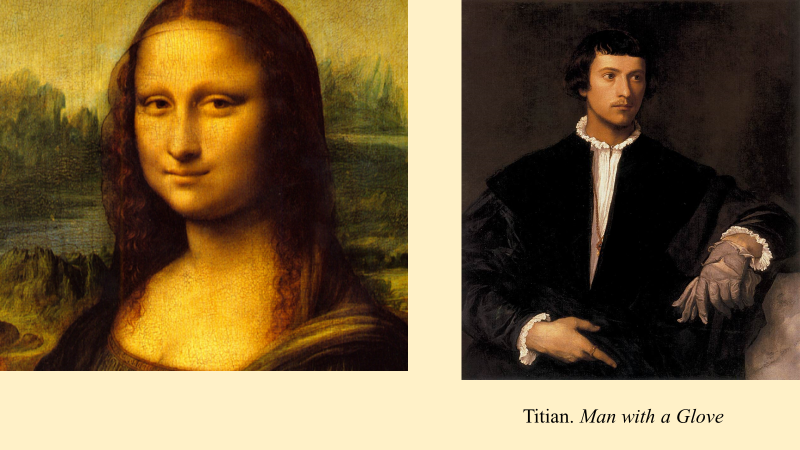

to rid ourselves entirely of the belief that paintings like the Mona Lisa, or Titian’s Man

with a Glove, for example,

“represent” certain people, or that novels like War

and Peace or Balzac’s Père

Goriot – “represent”

life in a certain

place at a certain period of history. And from there, it seems just a

short

step to assume that representation is what art is really about.

Nevertheless,

it is this belief – that art is essentially representation – that I

want to question

today, building my case on an excellent analysis by André Malraux in one

of his major works on

the theory of art – Les Voix du silence –

a work, incidentally, that writers in aesthetics, both here in

Australia and

overseas, almost never read, and whose very existence they often seem

quite unaware

of. Malraux does not, of course, argue that art – visual art for

example –

never represents anything. Such a claim would obviously not be

sustainable. But

he does argue – and argue quite passionately – that the essential

purpose of art is not to represent the world, whether or

not, as in the case of the two paintings I have just mentioned, something is obviously represented.

Malraux’s

analysis here, as this implies, is not about individual works, but

about the fundamental nature and purpose of

art –

the general function it performs in human life – whether we’re speaking

of

visual art, literature or music. I

won’t

have time to explain his position in full, but I do want to comment on

certain aspects

of his argument that are relevant to our conference’s topic.

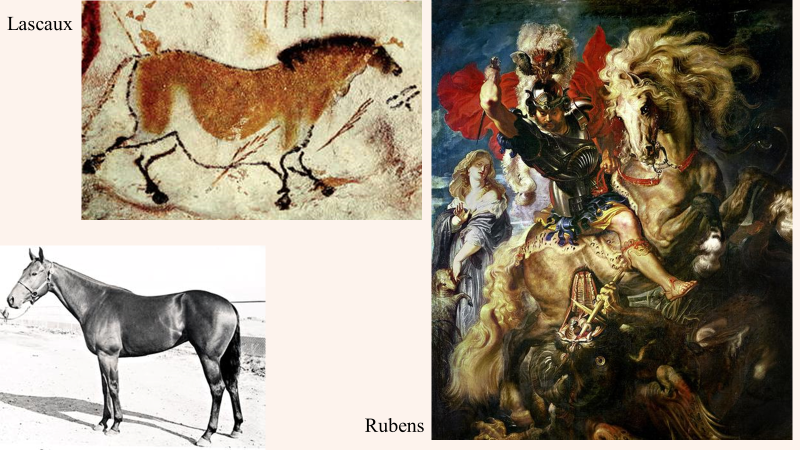

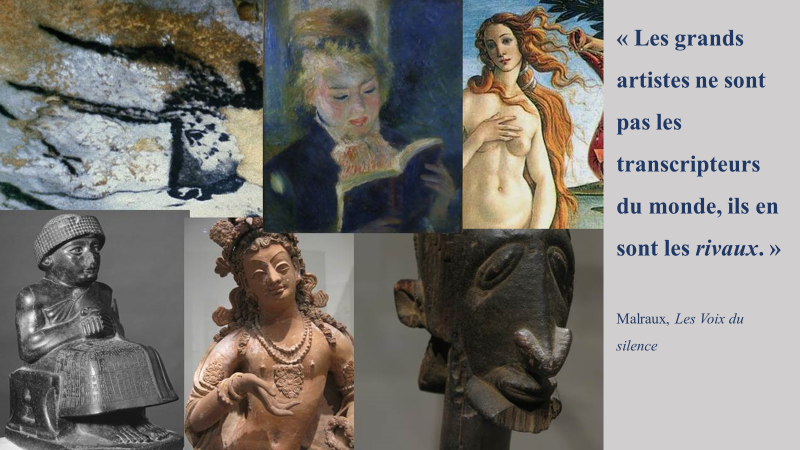

Let me

begin in a quite practical way by showing three images – in this

instance of

horses. The one at top left, as you no doubt know, comes from the caves

of

Lascaux and was painted some 19,000 years ago; the one on the right is

a

spectacular baroque fantasy of St George

and the Dragon by Rubens, painted in the seventeenth century;

and the other

is a fairly unremarkable photograph of a horse that I happened to find

on the

internet.

Now, at

one level, it seems perfectly reasonable to say that these three images

are all

representations of horses, in each case in a different style – the

style of an

unknown Palaeolithic cave painter, the style of Rubens, and the style

of a

photograph. And if that seems a reasonable thing to say, one inference

we might

feel inclined to draw is that each image is a different stylistic

rendering of an

underlying, stylistically neutral

representation of a horse – that is, an underlying representation that

is free

not of only of these three styles,

but of any specific style – a

basic,

style-less image, so to speak. Seen in this light, the notion of style

would, as

André

Malraux points out, be understood as “successive varieties of ornament

added to

an immutable substratum”[1]

–

that is, a kind of “added layer” which, in theory at least, could be

jettisoned

altogether if the artist so desired. This tempting idea is what Malraux

calls

“the fallacy of a neutral style”. In visual art, he writes, “it has

been

assumed for centuries that there exists a styleless, ‘photographic’

kind of

drawing (though we know now that every photograph has its share of

style) which

would serve as the foundation of a work, style being something added.

This is

the fallacy of a neutral style.”

Now, I

must in all honesty confess that before I started to think seriously

about

these issues, I myself probably subscribed to a view something like the

one

Malraux describes, and perhaps I am not only one who has done so? After

all,

the proposition seems plausible enough on the surface, does it not?

Don’t we

often tend to assume that the specific style in which an object is

portrayed is

something “added” as Malraux writes – so that Rubens, for example, adds

a

rather more flamboyant style to his horse than the Lascaux painter and

the

camera? And don’t we often tend to assume, even if in a vague sort of

way, that

if we were to somehow to remove this something “added”, we would be

left with a

basic, style-free image of the object – an “immutable substratum” to

borrow

Malraux’s phrase? I

suspect I had a

definite tendency to think that way – and if I am ruthlessly honest, I

suspect

I thought about literature in a similar way, assuming that each

novelist, for

example, adds his or her particular style to a kind of underlying

neutral style

which, as Malraux says, served as the foundation for the various final

products.

As he so

often does, however, Malraux encourages us to examine our assumptions

more

carefully. The basis of the idea of the neutral style, he writes, is

the idea

that a living model can be copied “without any interpretation or

expression”.

But, in reality, he points out,

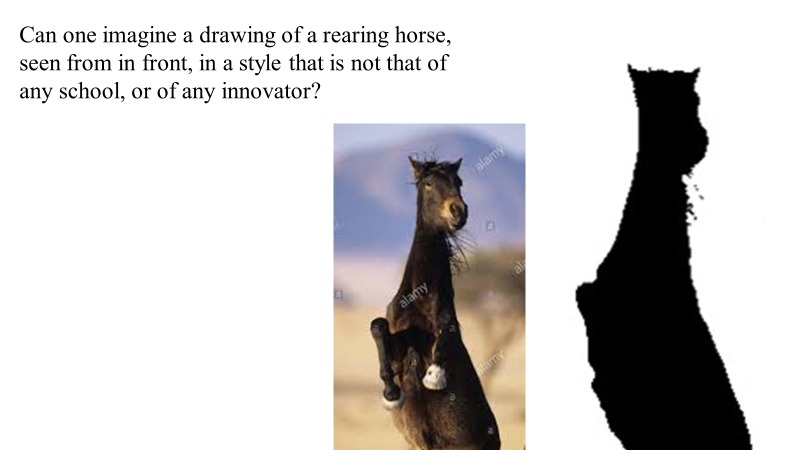

No such copy has

ever been made. In drawing, this

notion can be applied only to a small range of subjects [such as] a

standing

horse seen in profile…Can one imagine a drawing of a rearing horse,

seen from

in front, in a style that is not that of any school, or of any

innovator?

The notion of a

style-less drawing, he writes,

springs in large

measure from the idea of the

silhouette: the basic neutral style in drawing would be the bare

outline. But

any such method, if strictly followed, would not lead to any form of

art, but

would stand in the same relation to drawing as an art as the

bureaucratic style

stands to literature.

The

argument is intriguing, but is it correct?

Well, one can test it fairly easily. My

photoshopping abilities are

unfortunately rather limited but I’ve managed to reduce the photograph

of

certain object to its silhouette. (I would have included a bare outline

as well

but that proved to be beyond my capacities.) Here is that object. What

exactly

is it, I wonder?

Well, with

a little imagination we can probably manage to make out what it is. I

took my

cue from Malraux’s statement and chose a photograph of a rearing horse,

seen

from in front – though I wasn’t able to find one taken from exactly in

front.

The

silhouette makes perfect sense once we see the photograph, but without

it, we

struggle a little, do we not? – and we’d struggle even more, I suspect,

with a

silhouette or outline from directly in front. The silhouette or the bare

outline shows us an image “without any interpretation or expression”,

to borrow

Malraux’s words; and in this case, we don’t even have the

interpretation or

expression afforded by a photograph. But the result is not the readily

recognisable image of a horse executed in a “neutral style”: it is not

a

“style-less” image of a horse – an immutable substratum; it is merely

an image

that, in a case such as this, borders on the unintelligible – something

not

terribly far from a meaningless blob.

Now,

already we can perhaps see that Malraux’s analysis poses a major threat

to the

proposition that art is essentially a form of representation.

Philosophers of

art define the idea of representation in various ways, not all of which

are

very helpful, but at their core, most definitions imply a close and

direct

relationship between the work of art and what one might loosely call

“the

outside world” or “reality”. If art is essentially representation, the

arguments imply, its function relies heavily on a presumed capacity to

reflect

that world – to hold a mirror up to nature in Hamlet’s words.

Seen in this

light, the essential task of the artist is to effect a kind of

transposition or

transcription of the outside world, or “reality”, onto the surface of a

canvas

or into the pages of a novel. And not surprisingly, this thinking often

goes

hand in hand with the familiar claim – quite understandable in this

context –

that a prime virtue of the true artist is “faithfulness to reality”.

And going

on from there, taking what seems to be the next logical step, one might

even

argue that a neutral style, that

would transcribe reality with maximum faithfulness to nature and

minimum

“interference” by the artist’s style, or even none at all, might be a

real

possibility.

Malraux’s

analysis suggests that thinking of this kind rests on a basic

misunderstanding.

To the extent that it is even conceivable, a neutral style would not be

pure,

unalloyed realism but a form of depiction that had in fact abandoned

all but

the last vestiges of the procedures available to art. In visual art, it

would,

as we have seen, be at best the bare outline or the silhouette. In

literature,

it would, as Malraux suggests, lead merely to the commercial or

bureaucratic

style where, in a similar way, language tends towards a limited range

of

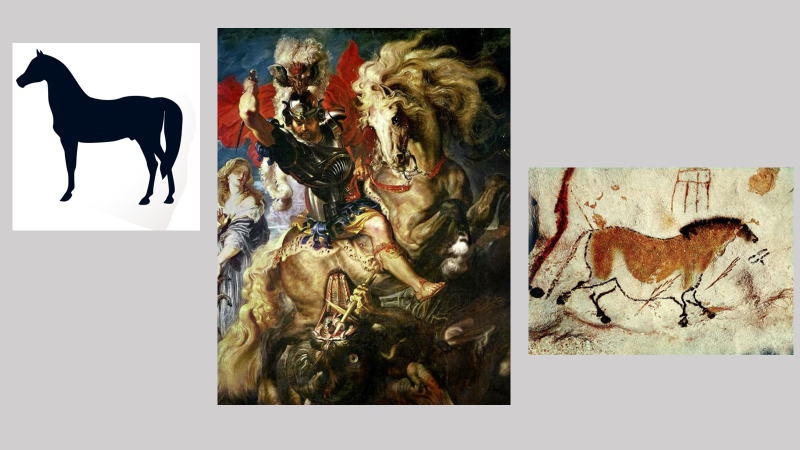

standard, “lifeless” forms. To the extent it is conceivable, in other

words, a

neutral style would result at best in the

sign – that is, to those limited uses of visual forms or

language that

merely suggest, or “point to”, living forms – as a silhouette of a

standing

horse might be used to indicate the presence of horses – but it would

stop well

short of portraying any such form,

as

Rubens and our Palaeolithic painter do. Which is why, incidentally,

Malraux

gives scant support to semiotic theories of art. He is happy to agree

that art

sometimes makes use of signs, but

in

itself, he argues, the sign is at best only an embryonic form of art.[2]

`

But if art

is not essentially representation,

what is it? To explore Malraux’s answer, I’d like to approach our topic

from a

slightly different angle. In the same section of Les

Voix du silence I’ve been discussing, Malraux reminds us of

an

obvious point that we – or at least I – often tend to forget. He points

out

that painting (like the photograph) always involves a process of reduction – that is, a process by which

the painter reduces a world of three dimensions to one of two

dimensions. This

being so, the painter’s task inevitably requires a process of

selection,

exclusion, and re-ordering – in short, a process of transformation

– a process in which, even if the aim is to create

an illusion of a three-dimensional reality (as in Renaissance art for

example),

the painter is not transcribing or transposing the outside world, but transforming it, that is, quite

literally creating another world, a

world different in kind from the

world in which we live and move.

One might

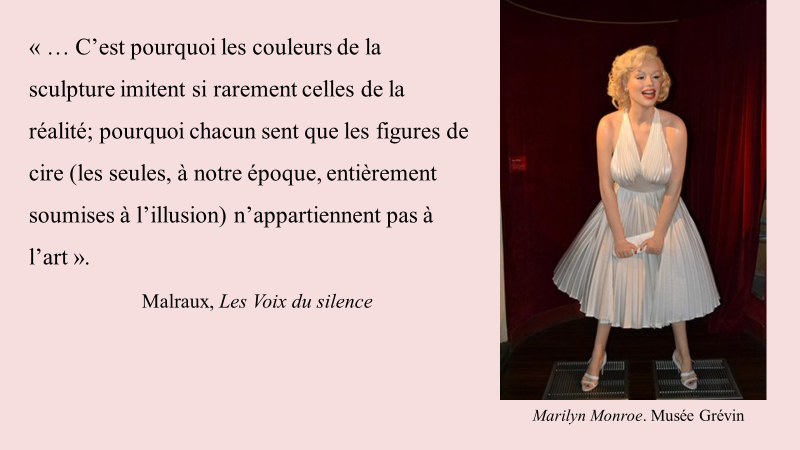

perhaps object that this argument does not hold good for sculpture

since, in

that case, the artist is not obliged to reduce three dimensions to two,

and

exact replicas of real objects are quite possible. But Malraux’s

rejoinder is

that sculpture too involves a process of reduction – a reduction of

“movement,

implicit or portrayed, to immobility”. And although, he writes, “we can

imagine

a still life carved and painted to look exactly like its model, we

cannot

conceive of its being a work of art. Imitation apples in an imitation

bowl are

not a true work of sculpture”. Which is why, he adds interestingly,

“colours applied

to sculpture so rarely imitate those of the real world; and why

everyone feels

that wax figures (the only forms in our time that are completely

illusionist)

have nothing to do with art”.[3]

Some

critics, including several art historians, have misread all this and

claimed

that Malraux’s argument is in fact intended as an attack

on representational art and that he has a bias against it– a

claim which, incidentally, reveals that the critics in question cannot

have

read Malraux with any care, given his enormous admiration for works

ranging

from medieval and Buddhist sculpture, to Titian and Rembrandt, to

modern

painters such as Van Gogh and Renoir, and many more. But in any case,

the

issue, as I have said, is not about individual works, or whether art

that

represents might somehow be better or worse than art that doesn’t –

questions

that Malraux would have doubtless regarded as absurd; our concern is

the quite

different matter of the fundamental nature and purpose of art. And in

that

context, Malraux’s argument is that representation, in the simple sense

of

including in a picture forms resembling real objects, is simply one of

the tools or techniques available

to art –

like the varied uses of line or colour. As a form of endeavour – as a

certain

kind of human achievement – he is contending, art is never essentially

representation. (“It is for the non-artist, not the artist,” he writes,

“that

painting is only a form of representation”.[4])

Art always involves the creation of another world – a rival

world, as he often says, a world that depends for its very

existence on a process of transformation of bare “reality” or “the

outside

world”.

A theory

of this kind, it is worth noting, offers a much clearer and more

coherent

explanation of the notion of style than the theory that art is

essentially

representation. If the goal of art is simply to represent – to

transcribe the

outside world into a novel or onto a canvas as faithfully as possible –

what

after all, is the function of style? Style in that case begins, as we

have

seen, to look suspiciously like a potential source of interference

– perhaps of distortion – and it’s no accident, I

think, that writers in aesthetics who claim that art is essentially

representation typically skirt around the question of style, or fall

back on

variants of the idea that it is, to borrow Malraux’s words again,

something

“added” or “successive varieties of ornament”. The proposition that art

exists

to create another world, however, gives a clear and decisive meaning to

the

idea of style. Styles are the very fabric of art; they are the

different ways

in which the artist accomplishes the transformation that creates a

rival world.

In some cases, those means might include the representation of real

objects; in

others, they may not. But in all cases, style is never simply something

“added”; it is the essential, indispensable means through which the

artist creates another world, “no

less necessary”,

Malraux writes, “when the artist is aiming at unlikeness than when he

aims at

life-likeness”.[5]

The role of representation

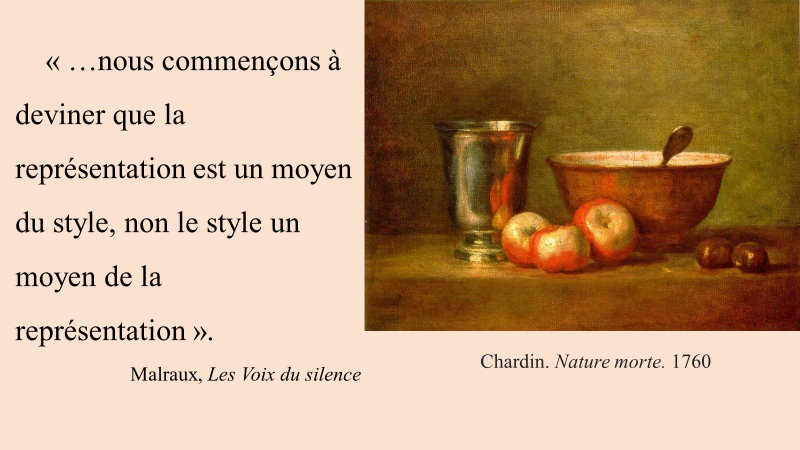

itself then becomes quite clear. “We are beginning to understand,” he

writes,

“that representation

is one of the devices of

style, instead of thinking that style is a means of representation”.[6]

There is

much more to say about Malraux’s theory of art. If art is the creation

of a

rival world, what is the purpose of that world? What function does it

perform

in human life? These questions go to the heart of Malraux’s theory of

art and explain

many of its fascinating features – including his revolutionary claim,

whose

importance is still widely unrecognised, that art does not endure

timelessly as

the West has believed for so many centuries, but through an endless

process of

metamorphosis. But those are questions for another day because my time

has now

expired.

[1]

Les Voix du silence, 540.

[2]

See

Les Voix du silence, 534, 543,

544.

[3]

Ibid. This would not of course preclude certain real objects – “objets

trouvés”

– being regarded as art, either as parts of a sculpture or as the

“sculpture”

itself. A piece of driftwood displayed as art is not viewed as a

representation

of a piece of driftwood (as a wax model is of a particular person).

[4]

Les Voix du silence, 538.

[5]

Les Voix du silence, 491.

[6]

Ibid., 553.

[7]

Ibid., 698. Emphasis in original. Malraux uses this same statement as

the

epigraph for his final volume on art, L’Intemporel.

Cf. also: “Like the painter, the writer is not the transcriber of the

world; he

is its rival.” L’Homme précaire et la

littérature, 152.