Myths about Malraux's Theory of Art

most seriously misunderstood.' André Malraux, 1973.*

Malraux's books on art, as one commentator writes, have been 'skimmed a lot but very little read'. As a result, his theory of art is surrounded by a cluster of simplistic and misleading myths which seem to be the result of superficial readings or simply relying on someone else's opinion. I have discussed most of these myths - often propagated by quite eminent figures in the history of art or aesthetics - in my books on Malraux's theory of art. Here are some of the common ones:

Myth 1. Malraux was an art historian.

This is said repeatedly. Malraux was an art theorist. The nature of his theory of art required frequent references to art history (a welcome change, one might say, from so many modern philosophies of art that shy away from providing specific examples) but he was not, and never sought to be, an art historian. Although always careful to ensure that his facts were as accurate as possible, Malraux’s aims were quite different from those of an art historian and he said so quite explicitly on a number of occasions. Much of the pointless hostility of art historians towards him (see below) seems due to their erroneous belief that he was somehow doing what they do.

Myth 2. Malraux wanted to isolate art from its historical and cultural context.

One encounters this myth (oddly out of

keeping with Myth 1) quite frequently. In

reality, there are very few, if any, art theorists who place as

much emphasis on the historical and cultural context of works

of art, and one only has to glance through a work such as The

Voices of Silence to realize this. (Try comparing

it with a textbook in analytic aesthetics, for example.)

Malraux certainly

didn't regard art as completely explicable in terms

of historical context - which is perhaps what some art

historians

struggled with - but the importance he places on it is,

nonetheless,

quite obvious. This myth has been repeated over and over

again, often

by prominent art historians (e.g. Gombrich, Hans Belting).

A variant of this idea is that Malraux believed that, as one writer puts is, 'the very placement of the object within the museum creates its importance and validity'. Malraux certainly believed - and said so clearly in Les Voix du Silence - that the placement of an object such as a Romanesque crucifix in an art museum fosters a change in its significance; but he never suggests that placing such objects in museums creates 'their importance and validity'. The latter claim would place Malraux in the camp of 'institutionalist' art theorists (Danto, Dickie et al) with whom he has nothing in common.

Myth 3. Malraux was not a systematic thinker and only gives us an "emotional response" to art.

This is

a huge

underestimation of the nature and value of Malraux's

theory of art. Malraux certainly does not write in the dry, clinical

mode of most textbooks on aesthetics – he often writes quite

evocatively – but it is an elementary error to conclude from

this

that

he doesn’t think clearly and profoundly. In reality, Malraux gives us a

carefully thought out, thoroughly coherent theory of art – and a

revolutionary one to boot, which escapes from the narrow, eighteenth

century view that art exists simply to provide so-called 'aesthetic

pleasure'.

Myth 4. Malraux simply borrowed the ideas of other thinkers.

Various sources are cited - Focillon, Elie Faure, Spengler, Benjamin, and so on. The claims don't stand up to even mild scrutiny. In fact Malraux was a highly original thinker. Even a daring one. That is perhaps partly why he has met with so much resistance...

Myth 5. When it comes to matters of art history, Malraux either gets his facts wrong or resorts to outright falsification. He is not a "responsible scholar". (Gombrich)

I

have examined this allegation in this

article which is extracted from a chapter of my first book.

In

fact, as I show, the boot is very much on the other foot: those who make these

claims have manifestly not bothered to read Malraux carefully. Their credibility

as 'responsible scholars' turns out to be in question. (Gombrich, for

example, doesn't even produce evidence; he simply makes his

accusations.) In fact, Malraux was very careful about these matters. No

one can claim infallibility where historical facts are concerned, and

Malraux didn't; but he was extremely well read in art history and

always strove to be as accurate as possible. There is ample evidence

for this.

Myth 6. Malraux despised art history and art historians.

Gombrich

seems largely responsible for this furphy. (One wonders if he

perhaps felt

somewhat threatened by Malraux.) In fact Malraux read extensively in

art history, had a large personal library, and at times collaborated

with art historians (see for example his 'Universe of Forms' series).

He himself was doing something fundamentally different from art history

as he made clear more than once (see Myth 1 above), and art historians

who understood this often admired his work.

There

is a sad irony in all this. The basic aim of his writings on art,

Malraux explained on several occasions, was to increase people's love

of art - not just their knowledge, their love. One might have hoped

that art historians would have welcomed this. Instead, many have simply

heaped invective on him.

Myth 7. Malraux was a "late Romantic".

This

silly myth also seems to owe its origin to Gombrich. Not surprisingly,

it is never supported by relevant evidence. Malraux has some very

interesting things to say about Romanticism, but to confuse his own

thinking with Romanticism is an elementary mistake.

The myth dies hard, however. In

his book The Adventure of French

Philosophy,

Alain Badiou describes Malraux’s

stance as 'romantic individualism'. Malraux was neither a romantic nor

an individualist. To describe as an individualist someone whose early

novels placed such a strong emphasis on fraternity, (cf. La Condition Humaine)

and whose later works focused so strongly on an evocation of the

human

(i.e. not simply the individual), is

plainly inaccurate and suggests that, once again, Malraux has been skim

read. An important aspect of Malraux's thought, as a number of

scholars have recognised, is precisely

his reaction against

individualism.

This misinterpretation appears to result, once again, from skim-reading. Nothing in Malraux's theory of art supports the claim, and he rejects it explicitly on numerous occasions. Malraux certainly believes that art responds to the same fundamental dimension of human experience that religion addresses. (So art is not, for example, merely a source of 'aesthetic' delectation.) But art, he argues, responds in a quite different way. Claims that he equates art and religion only serve to mislead.

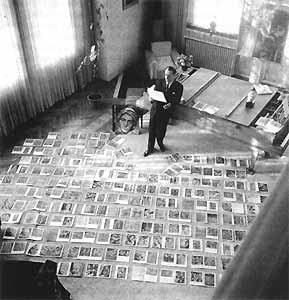

Myth 9. The musée

imaginaire is simply a vast collection

of photographic reproductions of works of art.

This misundertanding is widespread. The concept of the musée imaginaire is the aspect of Malraux's thinking with which his name is most frequently linked but, unfortunately, critics who discuss it rarely seem to have read him carefully, leaping to the facile conclusion that he is simply talking about photographic reproduction. Typical comments are:

- The “rich display of reproduced images,

open to us on page and screen, [is what] Malraux called ‘the imaginary

museum’” (Alberto Manguel, 2000)

- 'In a way we are already within Malraux’s

imaginary museum. There is no end of beautifully produced art works in

monographs on particular artists, movements or epochs'. (Matthew

Kieran, 2005.)

Comments such as

these trivialize Malraux's thinking. The concept of the musée

imaginaire is much more substantial and far more

interesting.

Myth 10. Malraux wanted to eliminate art museums and replace them with reproductions.

Anyone remotely familiar with Malraux's work as France's Minister for Cultural Affairs, where he showed such strong interest in the conservation of art, and of art sites, would know that this proposition is quite absurd. Malraux believed photographic reproductions play an important role in familiarizing us with visual art, but nowhere does he suggest that they could or should replace the original. The suggestion that he wanted to eliminate art museums is simply bizarre. (However, he did not subscribe to Benjamin's notion about the 'aura' of the original. I suspect he would have regarded the idea as somewhat superstitious.)

This myth

is formulated in a variety of ways. Witness this comment in a

2011 issue of the New

York Observer: 'André Malraux’s adage that an art book is a

"museum

without walls" displeased those who believed art must be seen in

person.'

First, Malraux never simply equated the musée imaginaire

with images in

art books (see Myth 9 above) but more importantly here, he

never suggested that it is no longer necesssary to

see the originals. Many of his initiatives as

Minister for Cultural Affairs were directed precisely at

increasing people's opportunities to

see works of

art.

Myth 11. Malraux was a "formalist" or (alternatively) a "subjectivist".

These notoriously vague terms are often thrown around. Merleau-Ponty, for

example called Malraux a 'subjectivist'. He was neither that nor a

'formalist'. I examine these misleading claims in my books.

Myth 12. Malraux is a "modernist".

The

term 'modernist' has about twenty different definitions at a

conservative estimate so it's not always clear what this

myth is about.

One intended implication seems to be that Malraux is somehow passé

- a very odd proposition since in all kinds of ways his thinking

is well ahead of

many contemporary thinkers. He is the only one, for example, who

addresses the pressing question of the relationship between art and

time (i.e. the capacity of art to 'live on'). He is the only one who

establishes a

substantive link between the theory (philosophy) of art

and art history. (Compare 'analytic' aesthetics, for example.) He is

the only one who deals squarely and convincingly with the fact that

past cultures had no concept of art. And, above all, he is the only one

who offers a persuasive alternative to the tired, eighteenth century

notion that art equals beauty and exists simply to provide 'aesthetic

pleasure' (an idea which, ironically enough, still crops up in

'post-modernist' accounts of art.).

Myth 13. Malraux believed in the

idea of "art for art's sake".

This claim is advanced in a recent textbook on aesthetics (Stephen Davies et al., eds., A Companion to Aesthetics, (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 129.) There is not the slightest evidence for it and the proposition runs counter to the very foundations of Malraux's thinking, which ascribes a clear purpose to art. Art, in his well-known statement in The Voices of Silence (which I explain in some detail in my first book) is an 'anti-destiny'.

Davies' book tries to shore up its claim by suggesting that Malraux has a 'contextless approach to art'.This proposition, which recycles the claim in Myth 2 above, is also groundless. As even a cursory reading of The Voices of Silence or The Metamophois of the Gods reveals, context figures very prominently in Malraux’s writings on art – much more prominently, one might add, than in the school of 'analytic' aesthetics to which Davies’ volume belongs, in which, ironically enough, discussion of art is very often - and even as a matter of principle - historically 'contextless'.[2]

Both these claims, once again, suggest a superficial reading of Malraux's books on art. It is a great pity that comments like this find their way into books apparently intended to provide students with reliable accounts of theories of art.

Myth 14. Malraux's books on art are "unreadable".

This myth is bandied about from time to time. Malraux's books on art can certainly be challenging, especially if one has only a limited knowledge of art and its history, because he frequently refers to particular works and doesn't limit himself to the European tradition. He assists his readers by providing lots of reproductions but he obviously can't do so for all the works he mentions so one sometimes finds it necessary to fill in the gaps (not difficult these days with the Internet) and if one is unwilling to do that, things can occasionally become a little difficult. (Malraux always chooses important and interesting works so looking them up is never wasted effort.)

This focus on the concrete facts of art history (even though, as I've said, he is not writing art history per se), means that Malraux's books on art differ markedly from most modern textbooks on aesthetics which rarely demand anything more than a superficial knowledge of the world of art (and, of course, leave their readers in much the same condition at the end). He is extremely knowledgeable about art and writes with great care, so his books repay in spades the extra effort sometimes required. I suspect that those who find him 'unreadable' may simply have been unwilling to make the effort. Malraux is certainly being read and studied more and more in France. (See the long list of articles and books by academic commentators on the website at http://www.malraux.org/).

Myth 15. André Malraux’s theory

of art is a “grand narrative”.

Myths about Malraux's life.

While on the subject of myths,

it is perhaps worth mentioning the mythology that has grown up around

Malraux's

life. I have discussed this matter briefly in my Letter to Quadrant on this

site. The extracts below from my book (which, however, is principally

about Malraux's thought,

not his life) are also relevant. In general, the fascination

with Malraux's life, understandable though it perhaps is, has

had

the unfortunate effect of distracting attention from his thought, which

is far more important.

Extracts from Art and the

Human Adventure: André Malraux’s Theory of Art:

… Although he seems to have seen himself first and foremost as a writer, Malraux’s biography bears little resemblance to the stereotype of the French intellectual whose life is confined mainly to his or her study, or to a Left Bank café. His remarkably eventful life included an ill-starred expedition to Indochina in his early twenties in search of bas-reliefs from lost Khmer temples, active involvement in the anti-Fascist Popular Front in the 1930s and then in the Spanish Civil War, service in the French army at the outbreak of World War II, participation in the French Resistance ending in arrest by the Gestapo, action in a French armoured brigade in the latter stages of the war, and ministerial posts in de Gaulle’s governments, most importantly as a very active Minister for Cultural Affairs.

As one might expect, this varied and colourful career has attracted the attention of some writers whose interest in Malraux lies more in what he did than in what he wrote, and biographies have become something of a minor industry... [Moreover] involved as he was in some of the major historical events of his times, Malraux acquired both strong supporters and determined adversaries, and the resultant polarisation of opinion has inevitably coloured much of what has been written about his political commitments and his life generally. As one writer pithily puts it, Malraux can appear, depending on what one reads, as “a Communist, an Existentialist, a neo-Fascist at heart, an aesthete who has turned his back on reality, [or] an unofficial Catholic”[1] – and this list by no means exhausts the descriptions that have been applied to him. Predictably enough, it has now become quite difficult in many instances to separate fact from speculation – and sometimes from sheer invention – and much of what purports to be accurate biographical information about Malraux is of very doubtful reliability. The principal events of his life, such as those mentioned above, are not in doubt, but there is much that is uncertain, and possibly likely to remain so...

(PS: A good summary - in French - of key events in Malraux's life can be found here.)

A common myth about Malraux's

life is that "after

the war, he gave up a life of action and devoted himself

to writing books about art".

[1] Robert Hollander, Introduction to André

Malraux, The Temptation of the West, trans. Robert

Hollander (New York: Jubilee Books, 1974), vi. Assessments sometimes

vary within one book. In the space of three pages, Herman Lebovics

describes Malraux as a “posturing, often flamboyant artist” with

“suspect personal qualities”, and an “amazing man” who as “a leader of

comrades” inspired “deep admiration and loyalty”. Herman Lebovics, Mona

Lisa’s Escort: André Malraux and the Reinvention of French Culture

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 105–107. In any case, all

this, as I say, is simply a needless distraction from the much more

important topic of Malraux's achievement as thinker

and

writer.

[2]

Cf. for instance, the comment by

Peter Lamarque (a representative of the analytic school) that, “Other

approaches [apart from analytic aesthetics] exist, of course, notably

that

associated with Continental philosophy, which is more historically

oriented.

The analytic approach is rooted in the analysis of concepts (albeit

increasingly informed by work in the empirical sciences) and tends to

examine

issues about the nature of art and the aesthetic qualities of objects

in an

ahistorical manner, even if noting and evaluating ideas

from earlier periods”. Peter Lamarque, Analytic

Approaches to Aesthetics: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Introduction. (Emphasis added.)

* Malraux made this remark in a personal letter to a friend. He never engaged in polemics about his work even when, as with critics such as Georges Duthuit and E. H. Gombrich, the attacks were highly inaccurate and offensive (e.g. Duthuit's intemperate book doesn't shrink from calling Malraux a 'fraud'; Gombrich is only slightly less abusive.) I discuss Gombrich's and Duthuit's comments in my book.