The Modern Universal World of Art

I

would like to take an historical approach to the topic of our

conference. That

is, rather than consider what might constitute an artworld at a

particular

point in time, I’d like to look back across

time and discuss a major transformation – a revolutionary

transformation in

fact – that has taken place in the world of art over the past century.

The

event I want to consider has been completely ignored in modern

aesthetics, and

one will search in vain in aesthetics textbooks for any significant

discussion

of it. That, however, is not an indication of the importance of the

topic, but

rather of one of the shortcomings of modern aesthetics – an issue I

will say a

little about towards the end of my remarks.

Let me

begin with a broad question: What

is the

nature of our modern world of art? What does it encompass – speaking in

general

terms?

We can

find the answer to that simply by thinking about the collections we

encounter every

time we cross the threshold of a major art museum, or indeed, when we

browse in

the art books section of a good bookstore.

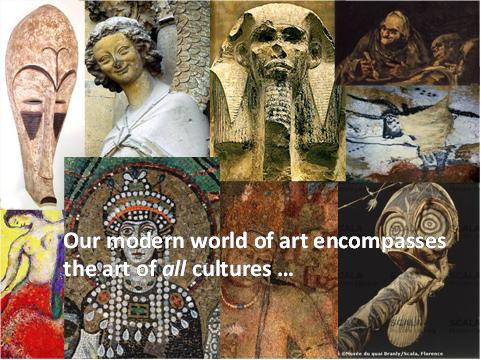

Our modern world of art encompasses the art of all cultures – or at least of those whose art is still extant. It includes the traditional field of Western art from the Renaissance to the present day, but it takes in much more besides. It includes pre-Renaissance art such as Gothic, Romanesque and Byzantine, and also, very prominently, the works of a wide variety of non-European cultures, past and present, such as ancient Egypt, Pre-Columbian Mexico, ancient China and India, Africa, the islands of the Pacific, and even Palaeolithic times. In short, the world of art we know today has no boundaries – geographical or historical: it is, in André Malraux’s apt phrase, a “universal world of art”. And most of us today accept this without so much as a second thought. We can hardly imagine things being otherwise.

But there’s the rub. Things have been otherwise. In fact they were otherwise for a much longer period of time than they have been the way they are now. But so familiar is our universal world of art that we forget just how recent it is, and how different it is from the world of art that preceded it. And we also forget how rapidly it emerged and supplanted what went before.

Let me enlarge a little on all this.

Near the beginning of his fascinating book, The Metamorphosis of the Gods, André Malraux imagines the poet Baudelaire miraculously brought back to life and taken on a guided tour of one of today’s major art museums whose collections include substantial numbers of objects from our universal world of art – the Louvre, for example. Malraux, I should explain, considers Baudelaire to be one of the nineteenth century’s most astute and sensitive art critics, but he nevertheless imagines his astonishment as he explores today’s Louvre. Baudelaire, Malraux writes, would surely conclude that large areas of the institution are now given over to objects that have nothing to do with art.

The point Malraux is dramatising by Baudelaire’s imaginary time travel experience is simply that the world of art in the nineteenth century was strikingly different from ours. For Baudelaire and his contemporaries – and for the three or four centuries before that – the world of art had clearly defined boundaries: it was European art since the Renaissance plus selected works from Greece and Rome. Those were the limits. Anything beyond them was not just bad art; it was simply not art at all.

So, for our forebears, prior to the beginning

of the twentieth century – not so long ago after all – there was no

question of

a universal world of art. Art was Raphael, Veronese, Poussin, Watteau,

David,

and Delacroix – to give some well known examples – and there was no

question of

placing these works under the same roof as, say, African masks,

Pre-Columbian

figurines or Sung landscapes – or indeed beside Gothic or Romanesque

sculpture

or Byzantine mosaics. Objects from cultures such as these only began to

enter

art museums in the early years of the twentieth century; before that

they were

simply not candidates. Just as we today accept our universal world of

art

without a second thought, so art lovers until a century ago accepted

their much

narrower world of art without a second thought. Like Malraux’s

imaginary Baudelaire,

they would have concluded that today’s art museums have been invaded by

large numbers

of objects that have nothing to do with art.

Now, I imagine someone might say: “Well, after all, is this so surprising? From the fifteenth century onwards Europeans had increasing contacts with other cultures through trade and colonisation, and there was also a growing interest in history and archaeology. So it follows naturally – doesn’t it? – that the world of art would expand as well and that we would eventually arrive at a universal world of art.”

This explanation has an obvious surface appeal but unfortunately it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. One troublesome fact is that many of the cultures whose works began to enter art museums in the early twentieth century had been known to Europeans for long periods of time, but their artefacts had always been seen simply as fetishes, idols, or curios – never as art. In the words of one writer:

Although

primitive artifacts were known to Europeans from the time of the great

explorations of the New World and the Far East from the 15th century

onwards …

there was virtually no aesthetic interest in such artifacts as works of

art

until the early years of the 20th century. Gold objects from

Pre-Colombian

Mexico and Central and South America were melted down and the valuable

raw

material shipped back to Spain; a few pieces were taken back to the

home

countries as evidence of the culturally savage and barbaric state of

the

natives; and what aesthetic response there was was largely one of

horror at the

ugliness and brutality supposedly symptomatic of these savage, heathen

works of

the devil.[1]

Or as André Malraux writes, making the same point:

We

would

have become aware earlier of the world of art that came into being with

contemporary civilization if we had not confused it with a previous

development

– if we had not seen it as the inevitable consequence of our colonial

conquests, our explorations and our archaeological expeditions. But did

the

West discover African art when it discovered bananas? It certainly did

not

discover Mexican art when it discovered chocolate. What African

explorers found

was not African art but fetishes; the conquistadors found Aztec idols

not

Mexican art.[2]

These strike me as very cogent arguments. And there is another one, no less substantial. Our modern, universal world of art encompasses not just works from other cultures but also from pre-Renaissance periods of our own, such as Romanesque, Byzantine and Gothic, and these also were excluded from the realm of art from the Renaissance onwards. But although consigned to an oblivion of indifference from then on, these works did not, after all, suddenly vanish into thin air. They remained in place dotted all over Europe in cathedrals and basilicas – in plain view, for all to see. So the introduction of these works into our modern, universal world of art clearly did not depend on colonial conquests or archaeological expeditions.

The event I’m describing – the emergence of our universal world of art – has, as I’ve said, been routinely ignored by modern aesthetics, and when one considers the significance of the event, this neglect strikes me, I must say, as little short of astonishing. I’m now going to describe that significance in a way that, at first blush, might seem a little far-fetched – but I think I can persuade you it is not.

Moving back somewhat in time, what does the Renaissance signify for us? In large part, it signifies the resuscitation of the works of Greece and Rome that Byzantine and Romanesque Europe had, for several centuries, treated with indifference or disdain – when they had not simply broken them up for building material. Now, in the same sense it seems to me perfectly sensible to say – as André Malraux argues – that the twentieth century has witnessed another Renaissance, with this difference that our modern Renaissance has been on a much vaster scale and has not just involved the resuscitation of the works of two ancient Mediterranean cultures but of cultures from the four corners of the earth, past and present. The Renaissance itself did not happen overnight and neither did our modern Renaissance. Ours occurred bit by bit over several decades – which is partly why, I think, it has escaped the notice of so many art theorists. But one only needs a perspective on art history stretching back further than a century – merely an eyeblink in the overall history of art – to appreciate the magnitude of the transformation, and to recognise that our world of art is vastly different from the one that preceded it.

Interestingly enough, if we look at the reactions of certain writers at the time the change was first beginning to make itself felt, we discover that they seem to have been far more aware of it than we are today. The art historian, Hans Tietze, for example, wrote in 1925 of the great revision of art history that had occurred since 1910, and of what he termed the “daily discoveries of new worlds, the hourly transvaluation of all values …[in which] the works of the Far East and Negro artists breathed a complete humanity that stirred the very depths of our being.”[3] Similarly, Élie Faure wrote in 1927 that

In

appearance an abyss lies between the Negro or Polynesian idol, for

instance,

and Greek sculpture at its apogee. Or between that idol and the great

European

painting [of the past].

“And yet”,

he continues

one

of

the miracles of our time is that an increasing number of minds have

become

capable not only of tasting the delicate or violent savour of these

reputedly

contradictory works and find them equally intoxicating; even more than

that,

they can grasp, in the seemingly opposed characters, the inner accords

that

lead us back to man and show him to us everywhere animated by analogous

passions …[4]

We

do not, of

course, need to agree with Faure’s explanation

of the

event but it remains

the case, nevertheless, that for these two well-informed sources in the

1920s,

the transformation taking place was nothing less than “a transvaluation

of all

values” and “one of the

miracles of our time” – a revolution in the world of art that was

suddenly

placing Oriental, African and Oceanic art, for instance, on equal

footing with

what Faure calls “the great European painting”. Strangely, however, a

kind of

historical amnesia has set in since then – most astonishingly even in

the world

of aesthetics itself. This “transvaluation of all values”,

the

birth of

this new universal world of art, has slipped by unnoticed as if nothing

had

happened, when in

reality there has been

in our time as radical a

transformation in the world of art as

there had been in the aftermath of the Renaissance.

Now, the obvious next step is to ask why this change came about and what, precisely, it signifies. That’s a fascinating path to follow and a very rewarding one, but I’m not going to attempt it today because I just don’t have time. I’ve explored those questions in my recent book on André Malraux but unfortunately it’s not something I can do in a few words. I hope I have made it clear, however, that I do not think simplistic historical explanations will suffice. That is, I don’t believe it’s good enough to say that the event is simply the result of colonial conquests, archaeological expeditions and so on. An adequate explanation, I would argue, needs to take account of profound cultural changes in European culture that finally came to a head during the nineteenth century bringing about a transformation in the very way we respond to art – the way we see it – and also in the very notion of art itself. But, as I say, all that would take time to explain and I can’t pursue it today.

I do, however, want to offer some brief closing comments on the neglect of the issue I’ve discussed in modern aesthetics – because aesthetics, it seems to me, has the responsibility of helping us make sense of the world of art in which we live, and its failure to describe and explain the nature of our modern world of art strikes me as a very serious omission.

The school of aesthetics I principally have in mind here is what is sometimes called “analytic” aesthetics which is the prevailing form of the discipline in the Anglo-American world, as you no doubt know. I would have liked to say a little about “continental” aesthetics too, but again I’m limited by time so I won’t attempt that.

Now, analytic aesthetics, as you know, is an offshoot of analytical philosophy, and like its parent discipline, it has a strongly ahistorical approach to its subject matter. Analytic aesthetics treats art effectively as a timeless category unaffected by historical change except in incidental, peripheral ways. So it’s not really surprising – is it? – that the radical transformation I’ve described – this second Renaissance – has elicited no response from aestheticians of this stamp. The event, after all, was an historical event and historical events are effectively beyond their purview. So the issue becomes a non-issue.

Personally, I think that an aesthetics that sidelines history condemns itself to irrelevance but rather than pursue that broad proposition, let me just briefly look at one of the implications of treating the event I’ve described as a non-issue.

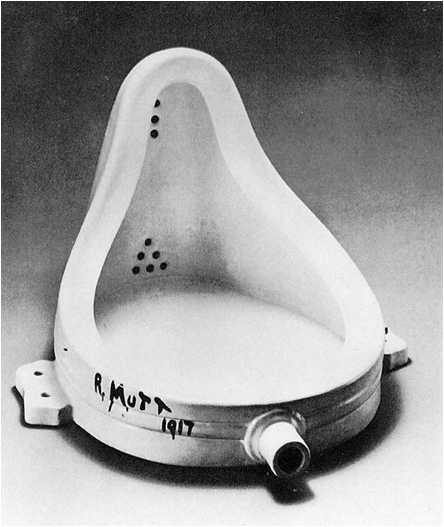

As we know, an enormous amount of ink has been spilt in aesthetics on the alleged transformation of a certain urinal and certain Brillo boxes into works of art. This is congenial territory for analytic aesthetics, of course, because the events are relatively recent and one can discuss them without seriously disrupting the basic assumption that art is a timeless category only marginally affected by history. And so, as I say, these two works have attracted an enormous amount of comment.

Yet when one places that debate alongside the question I’ve been considering, one is struck by something very odd. The change I’ve been considering has transformed large numbers of once despised idols, fetishes, images of gods, votive offerings and so on into works of art. So this transformation has not just affected a small number of objects from contemporary Western culture in which the notion of art already exists, but large numbers of objects from a wide range of other cultures, past and present, in which the notion of art was quite unknown. Putting the matter in concrete terms, it has transformed this Sumerian figure of Gudea of Lagash into art just as surely as – we are told – these Brillo boxes have become art. Yet analytic aestheticians have devoted a seemingly endless stream of comment to the transformation of the Brillo boxes while the transformation of objects such as the Gudea receives none at all. The inconsistency is, I think, self-evident.

These remarks are not intended to belittle Duchamp or Warhol. My own response to their works, I confess, is rather lukewarm but that’s not the point I am making. My concern is the extremely parochial nature of modern aesthetics – I mean of the Anglo-American “analytic” variety – parochial in the sense that it consistently turns it back on the history of art and assumes as a matter of unquestioned principle that art is a timeless category unaffected by history except in peripheral ways. This idée fixe not only removes the possibility of answering the kind of question I’ve raised in this paper; it virtually ensures that such questions will never be raised.

The truly regrettable aspect of all this, to my mind, is that it results in an aesthetics that’s incapable of discharging one of its key responsibilities – helping us make sense of the world of art in which we live. Every time we cross the threshold of a major art museum today we’re confronted with our universal world of art. Some of the objects – such as paintings by Cézanne – were, we know, created to be works of art in a culture in which that idea was familiar and made sense. But others – an African mask, for example – come from cultures in which the concept of art would have been unintelligible, and whose artefacts were not seriously considered for inclusion in art museums until the twentieth century. Yet, once in the art museum, we find ourselves admiring all these objects – the African mask and the Cézanne – as works of art. This is perplexing and, quite reasonably, we turn to aesthetics for an answer. But alas! it is an empty chapter in modern aesthetics and we are simply left to wonder. Modern aesthetics, we find to our disappointment, has nothing at all to say about one of the most astonishing developments in the whole history of art – the emergence of our modern universal world of art.

[1] H. Gene Blocker, The Aesthetics of Primitive Art (Lanham: University Press of America, 1994), 272.

[2] La Métamorphose des dieux, 24. Malraux is not of course denying the value of historical and archaeological research. His argument is that this was not the decisive factor in the context under discussion.

[3] Gombrich, “André Malraux and the Crisis of Expressionism,” 79. Gombrich cites as his source an essay by Tietze entitled “Die Krise des Expressionismus”, Lebendige Kunstwissenschaft, Vienna, 1925, 40. In this context, Gombrich is quoting Tietze as evidence of an “expressionist” theory of art which was influential at the time, and to which Gombrich mistakenly claims Malraux adheres. The important point for present purposes, however, is not Gombrich’s claim about Malraux but the “daily discoveries of new worlds, the hourly transvaluation of all values” to which Tietze refers. Gombrich himself seems to have been less than enthusiastic about the new horizons that were opening up. Cf. his remarks at the end of the essay cited here where he comments that “… we may come to see that our fathers and grandfathers were not quite wrong, after all, when they thought that we understand some styles better than others. That a Rembrandt self-portrait or a Watteau drawing ‘means more’ to us than an Aztec idol or a Negro mask”. Gombrich, “André Malraux and the Crisis of Expressionism,” 85.

[4] Élie Faure, History of Art: The Spirit of the Forms, trans. Walter Pach (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1930), ix.

This paper was delivered at a conference entitled "Artworlds" at the Australian National University, 8 October 2010. The images are from the PowerPoint show that accompanied the paper.

We can hardly imagine things being otherwise...

Baudelaire, Malraux writes, would surely conclude that large areas of the institution are now given over to objects that have nothing to do with art.

Just as we today accept our universal world of art without a second thought, so art lovers until a century ago accepted their much narrower world of art without a second thought.

... what aesthetic response there was was largely one of horror at the ugliness and brutality supposedly symptomatic of these savage, heathen works of the devil.

What African explorers found was not African art but fetishes; the conquistadors found Aztec idols not Mexican art.

The twentieth century has witnessed another Renaissance, with this difference that our modern Renaissance has been on a much vaster scale and has not just involved the resuscitation of the works of two ancient Mediterranean cultures but of cultures from the four corners of the earth, past and present.

This “transvaluation of all values”, the birth of this new universal world of art, has slipped by unnoticed as if nothing had happened.

Analytic aesthetics has a strongly ahistorical approach to its subject matter. It treats art effectively as a timeless category unaffected by historical change except in incidental, peripheral ways.

Gudea,

Prince of Lagash

(c. 2150

B.C.). Louvre

... an aesthetics that’s incapable of discharging one of its key responsibilities – helping us make sense of the world of art in which we live.

Modern aesthetics has nothing at all to say about one of the most astonishing developments in the whole history of art – the emergence of our modern universal world of art.