Fiction

and

Reality:

A Way

The

topic I wish to address today – the general relationship between

fiction and

reality – is one that is no doubt familiar to you all.

But

I’d

like

to

address

it

in a way that is rather

different from the ways it has been addressed up till now.

My

own

impression

is

that

debate

around this

topic

has become rather bogged down in recent years, and it seems to me it’s

time now

to pause and ask some fundamental questions about the issues at stake.

So that’s what I’d like to do – in the hope

that a new approach along the lines I will suggest might offer a way

out of

what is beginning to look suspiciously like an impasse.

The

question, then, is how we are to understand – to conceptualise – the

relationship between fiction and the so-called ‘real world’ or

‘reality’, and

in particular whether, and in what sense, fiction can be said to be a

source of

truth or knowledge about the real world. Most

of what I will say will relate to the

treatment of this issue by what is broadly termed analytic aesthetics,

but my arguments

also have implications for continental aestheticians, and towards the

end I

will add a brief comment under that heading as well.

***

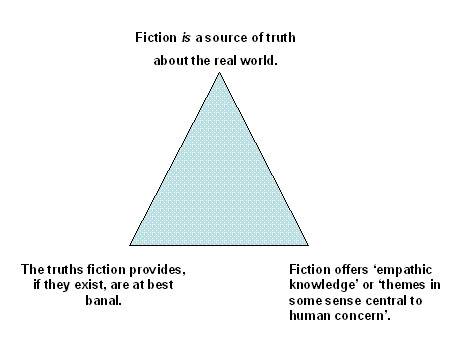

Within

the analytic school, there seem to me to be three principal answers to

the

question I’m addressing.

First,

there are those bold enough to suggest that fiction is often

a source of truth about the real world and that, to quote one

writer of this persuasion, ‘some fictional works contain or imply

general

thematic statements about the world that the reader, as part of an

appreciation

of the work, has to assess as true or false.’[1]

Then, at the opposite pole, are those who

deny that fictional literature can tell us anything true about the real

world –

or who believe that if it does, the best we can expect are, in

Stolnitz’s

words, mere ‘garden variety’ truths which are, in his words,

‘distinctly

banal.’[2]

And finally, there is a third approach which tries to steer a middle

course between

these positions and claims, in language that characteristically tends

to be somewhat

nebulous, that fiction certainly furnishes truths about the real world

but they

are not ‘fact-stating’, ‘propositional truths’, like those of science,

but

truths of a different kind. Fiction,

as

one advocate of this view puts it, allows the reader to acquire

nonpropositional, ‘empathic beliefs and knowledge’ which then become

available

to apply in real life situations.[3]

Or in the words of Lamarque and Olsen, who

adopt a similar stance, what matters in fiction is not the truth or

falsity

of statements about human life but ‘[themes] which [are] in some sense

central

to human concern and which can therefore be recognised as of more or

less human

interest.’[4]

Thus,

there seems to be a triad of basic positions – the view that fiction is

a source of truth about the real

world; the view that, if it is, those truths are at best banal; and

then the

somewhat elusive claim that literature is about a special kind of truth

called ‘empathic

knowledge’ or ‘themes central to human concern’. As

I read the literature on this topic, all

participants tend to take up positions somewhere within the boundary

marked out

by this triad, but there is little sign of an emerging consensus about

which

position, precisely, is to be preferred. The

debate has being going on for quite some time now and

there’s more

than a hint that it has begun to stall – as if all positions

have been

thoroughly explored, and the best one can hope for is a kind of entente

cordiale based on a deftly worded compromise.

***

I

would like, today, to suggest a more radical course of action.

I think it’s often a useful step when a

debate reaches an impasse as this one seems to have done, to go back to

the

starting point, re-examine the question

one is asking, and see if there’s not something in the nature of the

question

itself that’s blocking progress. And

I

want to suggest that this in fact the case. I

want to suggest that there is an unexamined difficulty

lurking right

at the heart of the question which is hindering clarity of thought and

which,

if left unexamined, will simply go on fostering confusion and

disagreement. Let me explain.

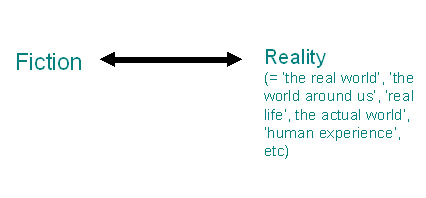

The

debate, as we’ve said, is about the relationship between fiction and

reality. So there are two

terms in our equation: on the one hand there are works of

fiction – such as Hamlet or Crime and

Punishment and many others –

and, on the other, there is something called ‘reality’ or perhaps ‘the

real

world’, or in alternative formulations sometimes employed, ‘the world

around

us’, or ‘real life’ or perhaps ‘human experience’.

At

first

sight,

this

seems

very

simple and

straightforward and we feel we’re ready to move straight on to whatever

the

next step might be. But in fact I

think

we need to pause right there because what we’ve said is not simple and

straightforward at all and we have already, perhaps without realising

it,

raised a very thorny question which we cannot afford to ignore.

Personally,

when I encounter the term ‘reality’ or an equivalent term of the kind

I’ve just

mentioned, in a philosophical analysis I usually begin to get uneasy.

What exactly do we understand by the

term? I

don’t mean:

does reality exist? I’m not asking the venerable philosophical question

about the

existence of the so-called external world. But

I am, nonetheless, acutely aware that ‘reality’ is one

of those chameleon-like

terms whose

meaning shifts in subtle but very important ways depending on the

context in

which it is used. So I need to know which

meaning, precisely, it is assuming in the present context – that is,

when we’re

speaking of the reality to which fictional literature is addressed.

I need

to

scrutinise

the idea and ensure that the meaning I’m ascribing to it is clear and

unambiguous,

and relevant to the context to which I’m applying it.

Because

if

I

don’t

do

that,

I’m simply embarking

on a philosophical analysis in which one of the key terms has been left

in a

conceptual limbo; and an analysis that begins in that way is obviously

destined

to achieve very little.

***

How

might

we clarify the idea? An

important first step in discovering what

we mean by the concept of ‘reality’ in the context of fictional

literature is to be clear as possible about what we do not

mean. And one way of

doing that is to compare literature

with other areas of intellectual endeavour – with history and politics,

for

example – and ask if the same understanding of the concept seems to

apply in those

cases, and, if not, what the differences might be.

Fortunately,

certain

writers

have

already

given

some

thought to this problem, and I’d like to spend a few moments

examining one analysis which strikes me as particularly insightful and

enlightening.

Early

in Stendhal’s novel La Chartreuse de

Parme, there is a celebrated scene set on the battlefield of

The

scene, as one astute critic points out, is a masterly depiction of the elusiveness,

from

the

point

of

view

of

the individual, of what one might conventionally call an ‘historical

event’. ‘When [he] describes

Fabrizio

searching for

the battle of

Stendhal

was

expressing, in his own nimble way, one of the great insights

of nineteenth century sensibility. It

was a flash of pure wonder at the utterly paradoxical relation between

an

individual destiny and whatever general significance might be attached

to an

‘historical event’. In fact, it was

the

splendid illustration of a myth which no historical venture, and no

amount of

sophistry, has thereafter been able to obliterate from our

consciousness…. The myth is about

man and

history: the more

naively, and genuinely, man experiences an historical event, the more

the event

disappears and something else takes its place: the starry sky, the

other man,

or the utterly ironical detail….[6]

The

key point is in those last lines: ‘the more naively, and genuinely, man

experiences an historical event, the more the event disappears...’

Recast to fit the terminology of our present

discussion,

the point might be formulated in the following way:

In

a

loose,

and

not

very

informative sense, literature and history can both

be said to be concerned with ‘reality’ or ‘the real world’.

But history’s focus is a collective

reality – the collective experience of men and

women. Like kindred

areas such as political or social thought, history’s concern is not an

individual’s thoughts and feelings in themselves

but only as

they are understood as part of a world in which people act upon, and

react to, one another. As a

conceptual possibility,

that is, history cannot be confined within the perspectives of an

individual life. It rests on an

intellectual schema

which cannot even begin to be drawn up without the initial resolve to transcend

the individual and his or her ‘private’ world of joys and sorrows, in

order to posit the existence of a collective world

which is

presumed to exist ‘among’ men and women when they act upon one another.

To state the matter in a paradoxical but

nevertheless

quite precise form, history concerns everyone, and for that

very

reason, concerns no one. This

is not of course

to imply that the events history records affect no

one. That claim would merely be

contrary to common sense. The point

is simply that the categories of historical

explanation – the concepts that claim to impose intelligibility and

meaning on the otherwise formless multiplicity of a collective event –

are, by their very nature, designed to illuminate something quite

different from the world as perceived and understood by the single

individual. Thus, to return to

Stendhal, Fabrizio

is unable to find the event called ‘the Battle of Waterloo’ which is in

fact raging all around him, and his attention constantly focuses on

seeming irrelevancies while a page of what we might quite reasonably

call ‘history’ is being written before his very eyes.

There

is

an

apparently

unbridgeable

gulf

– an ‘irretrievable disproportion’

as the critic I have been quoting calls it[7]

– between the forms of thought that confer meaning on a collective

event and the categories that shape the individual’s own experience.

Now,

this

analysis falls well short of a comprehensive account of the differences

between history and fictional literature. But

it

does, nevertheless, point to a crucial dividing line between their

fields of operation, and gives some initial shape and form to the

concept of ‘reality’ that applies in each case. The

‘reality’–, the ‘real world’, the ‘human experience’– with which

literature is concerned, the analysis suggests, is that of the living

human individual – the reality of the individual’s hopes, fears, joys

and sorrows. The reality of

history, by contrast,

is constituted on a plane that transcends the individual.[8]

There is, in other words, a fundamental difference

between

the reality with which fictional literature is concerned, and the

realities constructed by historical, social and political thought.

This conclusion, I should add, is in no way

inconsistent

with the obvious fact that certain works of fictional literature –

so-called ‘historical novels’ for example –sometimes incorporate

episodes from history, and occasionally even historical figures

(Napoleon being an obvious example). But

such works

characteristically make use of historical events as part of their plot

or setting , and there is a major difference between that and the quite

different proposition of attempting to close the gap between the

perspectives of individual experience and the categories of historical

explanation. So the mere fact that

history makes

periodic appearances in works of fiction is not an objection to the

claim I am advancing. It remains

the case, as I

have argued, that the ‘realities’ – the ‘real worlds’ – addressed by

literature and by history are of quite different kinds,

and to

confuse the two, or assume that they do not need to be distinguished –

as many theorists do – would be to ignore a crucial feature of the

concept of reality relevant to fictional literature.

It

would

in

effect

be

to

send the concept back to the definitional limbo

of which I spoke earlier.

***

Now,

I see

this analysis as an important first step in clarifying the notion of

reality in the context of fictional literature and I want to return to

these ideas in a moment. But before

doing so, I

would like, very briefly, to take the analysis a step further by

drawing another comparison – this time not between literature and

history, but between literature and science.

Debates

about

the relative importance of literature and science are not new.

One well-known episode is the ‘Two Cultures’

controversy

of the 1960s; another was the so-called ‘science wars’ debate of the

1990s which, while concerned principally with science itself, also had

implications for literature and for the humanities more generally.

One familiar line of argument in these debates goes

something like this: “Science aims

to give us an

account of reality based on objective evidence – evidence whose

validity is verifiable through public processes of experimentation and

demonstration. The reality of which

fictional

literature speaks, on the other hand, is much more questionable.

Literature has no equivalent to science’s public

tribunal

of experimental verification, and the knowledge it provides – if one

can call it knowledge – cannot be described as objective.”

Advocates

of

this

line

of

argument

might perhaps concede that, at their best,

works of literature give us an author’s sincere and carefully observed

view of the world, and this may intrigue or entertain us; but

ultimately, they would argue, the ‘reality’ in question is simply a

reality perceived by the author: it is necessarily only ‘subjective’.

As

I say,

this argument is a familiar one and I’m sure you’ve heard it many times

before. Yet familiar though it is,

it has a rather

irritating persuasiveness. We’d

like very much to

dismiss it as facile and superficial but where exactly is the flaw?

Where does it go wrong?

It

goes

wrong, in my view, through an ambiguity lurking within those over-used

terms ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ – and I think it’s very instructive

to reflect on that ambiguity for a moment.

Our

comparison between fictional literature and history,

you’ll

recall, suggested that the focus of literature is the world as

perceived and understood by the single individual – the reality of the

individual’s hopes, fears, joys and sorrows. History’s

focus

was

the

collective

reality

presumed to exist ‘among’ men and

women as they act upon one another – a reality which necessarily

transcends the individual. Neither

‘reality’, we

recall, emerged as more ‘subjective’ or ‘objective’ than the other;

they were distinguished simply by this individual/collective contrast.

Now,

what

exactly gives rise to the persistent tendency to associate science with

the idea of ‘objectivity’? In my

view, the reason

is very largely the methodology to which I have referred – science’s

well known procedures of experimentation, openness to public scrutiny

by peers, and willingness to have experiments repeated by others.

But, if we reflect on it, is ‘objectivity’ the best,

most

accurate, term to describe what takes place in such contexts?

The feature of this methodology that’s even more

obvious –

so obvious, in fact, that we easily take it for granted and overlook it

– is the importance placed on the impersonal nature

of the

processes employed and of the knowledge thus acquired – that is, the

importance of being able to reach the same conclusion irrespective

of who is asking the question. Like

history,

though in a different way, and for different reasons, science also

seeks

to

free

itself

from

anything

dependent on the perspective of the single

individual. Francis Bacon, that

well known early

advocate of the scientific method, wrote that one of the

‘illusions

which

block

men’s

minds’

is

that brought about by ‘the individual

nature of each man’s mind and body; and also in his education, way of

life and chance events’.[9]

Viewed from the standpoint of science, in other

words, the

individual, with what are regarded as his or her ‘merely personal’

perceptions, is a potential source of distortion

rather than of

knowledge. The

ideal perspective for

science is quite deliberately no-one’s perspective:

it is, so

to speak, a ‘public’ perspective, and the reality it pursues is, as a

matter of principle, an entirely impersonal reality.

The

danger of

the terms ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ in drawing distinctions between

science and literature is not in other words that they are entirely

irrelevant – because they are not – but that they can so easily be

misleading. While capturing to

a degree the

idea of impersonality, the term ‘objective’ can also very

easily suggest the idea of ‘correspondence with the facts’, or ‘what

reality is truly like’. ‘Subjective’,

similarly,

can suggest not just that which owes its origin and nature to

individual experience, but that which may also be biased and therefore

unreliable. Once we clear those

confusing

ambiguities away, however, we see that we are really dealing with intellectual

enterprises of quite different kinds.

Literature,

we

see,

is

concerned

with

the reality of the single individual’s

perceptions and understandings (which, incidentally, will also include

his misperceptions and misunderstandings).

Science

explores

a

reality

which

systematically

aims to exclude anything of

that nature. Both could with equal

justice claim to

be describing ‘what reality is truly like’ because they are looking at

what are, in terms of human understanding, two quite different kinds of

realities.

Of

course,

this analysis makes no more claim to provide a full account of the

methodology of science than the earlier discussion did to provide a

comprehensive analysis of the theory of history. The

comparison

with

science

does,

nevertheless,

throw further light on the

very troublesome issue raised in the introductory section of this paper

– the multiple meanings of the term ‘reality’ and of equivalents such

as ‘the real world’ or ‘the world around us’. The

reality addressed by science, the analysis suggests, is a specific kind

of reality, just as the reality of history is of a specific kind – and

both differ from the reality addressed by fictional literature.

Both science and history, albeit for different

reasons,

are obliged, as a matter of principle, to shun the domain of the

individual or the ‘merely personal’. For

literature, by contrast, the ‘merely personal’ is a sine qua

non

of its existence.

***

I

would now

like, very briefly, to draw out certain implications of this analysis

for current debates about fiction and reality. As

I

indicated earlier, most of what I say will relate to analytic

aesthetics, but I will say a little about continental aesthetics as

well.

How,

we

first

need

to

ask,

do writers in the analytic sphere define the

concept of reality in their deliberations on the relationship between

fiction and reality? I regret to

say that in my

reading of the relevant material I find very little attempt to define

the concept at all. One encounters

various cursory

formulations which are used as synonyms – such as ‘the actual world’,

‘the rest of the world in which [aesthetics objects] exist’ (that

variant is Monroe Beardsley’s) and even Stolnitz’s rather odd phrase,

‘the great world’. But obviously

none of that

really tells us anything more than the terms ‘the real world’ or

‘reality’ do in the first place. Certainly,

there

is nothing to give us any guidance on the issues I have raised in my

analysis.

So,

in the

absence of any explanation, we are, I think, obliged to draw our

conclusions from the way the term ‘reality’ is used.

That

is,

we

need

to

look

at particular treatments of the relationship

between fiction and reality offered by analytic thinkers and ask: what

kinds of phenomena do these writers cite as examples

of the

‘reality’ to which fictional literature is said to relate, and what can

we deduce from these examples about the notion of reality they seem to

have in mind?

I’m

sure you

can think of many instances yourselves; but the examples I have found

in discussions by analytic aestheticians of what is meant by ‘reality’

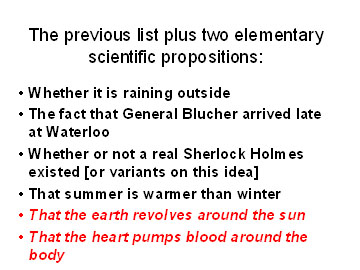

or the ‘real world’ include the following:

·

Whether

it is raining

outside

·

The

fact

that

General

Blucher

arrived

late at

·

Whether

or not a real

Sherlock

Holmes existed [and variants of this idea]

·

That

summer

is

warmer

than

winter

It

is, I

think, fairly difficult to infer any very clear definition of the

concept of reality from these examples but I am nevertheless going to

hazard what I think is an educated guess. I

believe

that the implied concept of ‘reality’ or ‘real world’ underlying

examples such as these is not very far from the concept of reality I

have identified in the case of science. The

examples, if we examine them, all suggest states of affairs that anybody

could verify – that is, an impersonal, ‘public’ reality which is, as

far as possible, independent of the perspective from which it is viewed.

Certainly, these examples don’t really evoke the

idea of

scientific methods of verification – propositions of this kind are,

after all, much simpler than those that science normally addresses –

but, it is interesting and revealing, I think, to see that we can easily

add one or two elementary scientific propositions to the list and find

that they do not seem out of place. [The

list

above

was

shown

on

a PowerPoint slide. At this point, I showed the

same slide with the following two additions:

- "That the earth

revolves around the sun;

- That the heart

pumps blood around the body." See

image at right.]

You

can no

doubt see now where I’m going with this, so I won’t labour the point

too heavily. If it is true, as I

have argued, that

a work of fictional literature, such as Hamlet or Crime

and

Punishment, addresses a reality of a specific kind which is not

the impersonal reality of science – any more than it is the collective

reality of history – ought we really be surprised that analyses that

assume the contrary seem, as we noted earlier, to be making little

headway and to be caught in an impasse? One

commentator has written recently that the relationship between fiction

and reality is a problem that ‘has proved remarkably resistant to

satisfactory resolution’[10]

which is perhaps a more diplomatic way of expressing the point. But

however

we

describe

the

situation,

the cause, in my view, is fairly

clear. The debate has resisted satisfactory resolution because it is,

in effect, trying to fit literature into a world in which it simply

does not belong – a world viewed from an impersonal

vantage-point, made up of publicly demonstrable facts, a world which,

as a matter of principle, needs to treat the single individual’s

perspective as not just as inadequate but even suspect. Asking

what

fictional

literature

can

tell

us about a reality of this kind is

guaranteed to lead us into an impasse for the quite simple reason that

literature is, by its very nature, addressed to a reality of a quite

different kind.

***

I

mentioned

earlier that I would also say a word about continental aesthetics but

it will be very brief. Continental

and analytic

aesthetics tend, as we know, to adopt very different approaches to

their subject matter but one feature they share is that theoretical

analyses in both contexts make extensive use of the notion of

‘reality’; and continental aesthetics, like its analytic counterpart,

is apt to comment frequently on the relationship between literature and

‘reality’, or ‘real world’.

Early

in his Aesthetic

Theory, Theodore Adorno, for example, writes that

Tied

to the

real world, art adopts the principle of self-preservation of that

world, turning it into the ideal of a self-identical art … It is by

virtue of its separation from empirical reality that the work of art

can become a being of a higher order…[11]

I

should be

honest and confess that I do not know precisely what this somewhat enigmatic statement

means, but I do note that it seems to rely heavily on concepts termed

‘the real world’ and ‘reality’ – the word

‘empirical’ adding very little in my view. Now,

nowhere in his Aesthetic Theory, as far as I can

tell, does

Adorno provide a clear definition of what he has in mind when he uses

these terms, so, as with analytic aesthetics, I am obliged to infer his

meaning from the contexts in which the terms are used.

This

quote

is

taken

from

an

early section of Aesthetic Theory headed

‘On the relation between art and society’ and that

in itself, I

think, is very revealing. In fact,

as one reads

through Adorno’s text, one repeatedly has the impression that when he

uses terms such as ‘the real world’ or ‘empirical reality’, he means a social

reality, or perhaps a socio-cultural reality, of some kind – but in any

event a collective reality – a reality understood,

as I said in

my earlier discussion of this issue, in terms of the collective

experience

of

men

and

women.

This,

I

should add, seems to be a prominent characteristic of much continental

theory, especially of

You

can, I

imagine, readily anticipate what I want to say about this.

Areas

of

continental

aesthetics

influenced

by

thinking of this kind seem to

me to suffer from the same problem I have identified in the analytic

approach – albeit for a different reason. Once

again, we see an attempt to yoke fictional literature to a reality

which is not its essential concern – in this case, a reality which, as

I argued earlier in my discussion of Stendhal, is, as a matter of

principle, separated from the world of fictional literature by an

unbridgeable gulf – an ‘irretrievable disproportion’.

In

analytic

aesthetics,

I

have

argued,

the debate seeks to link fiction to

a semi-scientific reality, a reality made up of the impersonal,

publicly demonstrable fact. Large

areas of

continental aesthetics, I would argue, attempt to link literature to a

reality which is just as alien – the world of collective experience

which, as we saw, is also, by its very nature, obliged to transcend the

world of the single individual.

***

One of the central challenges facing modern aesthetics – continental or analytic – is, in my view, to develop a theory of literature – and of art generally – that overcomes the fundamental problem analysed in this paper. Firstly, it is crucial in my view to recognise that the concept of ‘reality’, ‘the real world’ etc must not be left in a conceptual limbo and waved away with cursory phrases such as ‘the world around us’, ‘the actual world’, ‘the rest of the world in which [aesthetics objects] exist’, or ‘the great world’. The nature of the reality to which literature is addressed needs to be analysed and defined. It needs to be given the same degree of philosophical precision we would expect in any other part of our analysis – especially given that it is one of the two key elements in our equation. Secondly, I believe we need to recognise clearly that the reality to which literature – and all art – is addressed is a reality of a specific kind – which I have called, in very summary and general terms, the reality of the living individual, as distinct from the impersonal worlds of science or history. We need, in short, to situate literature in the context in which it rightly belongs and cease seeing it as a competitor in areas in which it has no essential place.

That

of

course is only a beginning. The

real challenge,

once having taken those steps, is to develop a theory of literature and

art that builds on this foundation – a theory based firmly on the

recognition that the reality to which art is addressed is a reality

perceived and understood by the single individual.

I

know

of

only

one

theorist

in recent times who has done this and that is

the much-neglected French theorist André Malraux, and those of

you who are familiar with his work will know that it offers us a

perspective on the world of art and literature very different from that

offered by analytic or continental aesthetics. But

my time has run out and I don’t intend to say anything more about

Malraux than that. I mention him

only because you

may perhaps think that my strictures against the analytic and

continental approaches leave us with a rather empty and desolate

landscape with nowhere else to go. I

think there is

an alternative. I think it is

perfectly possible to

develop a theory of literature and art which is based squarely where it

should be and which avoids the pitfalls I have described.

And

I

think

that

if

we

are to make real progress – and emerge from our

present impasse – that is the challenge that lies before us.

4 Peter Lamarque and Stein Olsen, Truth, Fiction and Literature, A Philosophical Perspective, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 332, 450.

5 Stendhal, La Chartreuse de Parme, Stendhal, Romans et Nouvelles (2) (Paris: Gallimard, 1952), 59-65. Fabrizio says to one of the French sergeants, ‘Sir, this is the first time I have been present at a battle. But is this a real one?’ (p.65)

8 This does not imply that literature is necessarily always concerned with individual differences (as suggested, for instance, in Rousseau’s well-known claim that Nature ‘broke the mould’ in which he was formed). The enormous range of human types which literary works present suggest on the contrary that the ‘categories that shape the individual’s experience’, to use the terminology I employed a moment ago, can take an endless variety of forms and need not revolve around a special value attached to an individual’s distinctive characteristics.

Another version of the paper,

entited Literature and

Reality, was

published in Journal

of European Studies,

Vol 31, Part

2, No 122, June 2001

I restated some of these ideas in a paper entitled Art and 'the real world' given at the 37th congress of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association (AULLA) at the University of Queensland on 10-12 July 2013.

...

debate around

this topic has become rather bogged down in recent years, and it seems

time now to pause and ask some fundamental questions about the issues

at stake.

Within

the analytic

school, there seem to be three principal answers to the question ...

... there

is an

unexamined difficulty lurking right at the heart of the question which

is hindering clarity of thought and which, if left unexamined, will

simply go on fostering confusion and disagreement.

Two terms in the

equation...

... ‘reality’ is one of those chameleon-like

terms whose

meaning shifts in subtle but very important ways depending on the

context in which it is used.

One

way of of

clarifying

the concept of ‘reality’ in the context of fictional literature is

to compare

literature with other areas of intellectual endeavour – with history

and politics, for example – and ask if the same understanding of the

concept seems to apply in those cases, and, if not, what the

differences might be.

‘the

more naively, and genuinely, man experiences an

historical event, the more the event disappears...’

There

is an apparently unbridgeable gulf – an

‘irretrievable disproportion’ – between the forms of thought that

confer meaning on a collective event and the categories that shape the

individual’s own experience.

...

the

‘realities’ – the ‘real worlds’ – addressed by literature and by

history are of quite different kinds, and to

confuse the two,

or assume that they do not need to be distinguished – as many theorists

do – would be to ignore a crucial feature of the concept of reality

relevant to fictional literature. It

would in

effect be to send the concept back to a definitional limbo.

What exactly gives rise to the persistent

tendency to

associate science with the idea of ‘objectivity’?

Like

history, though in a different way, and for

different reasons, science also seeks to free

itself from

anything dependent on the perspective of the single individual.

Literature

is concerned with the reality of the single

individual’s perceptions and understandings (which will include his misperceptions

and misunderstandings). Science

explores a

reality which systematically aims to exclude anything of that nature.

Both

science and history, albeit for different reasons,

are obliged, as a matter of principle, to shun the domain of the

individual or the ‘merely personal’. For

literature, by contrast, the ‘merely personal’ is a sine qua

non

of its existence.

How

do writers in the analytic sphere define the concept

of reality in their deliberations on the relationship between fiction

and reality? In my reading of the

relevant

material, I find very little attempt to define the concept at all.

...

in the absence of any explanation, we are obliged to

draw our conclusions from the way the term ‘reality’ is used.

I

am led to surmise that the notion of ‘reality’ or the

‘real world’ that many writers in the analytic tradition have in mind

in discussing the relationship between fictional literature and reality

is very much like that of science – that is, it is describable in

statements (like whether or not it is raining outside) that will be

true or false irrespective of who might be testing their veracity.

The

debate has resisted satisfactory resolution because

it is, in effect, trying to fit literature into a world in which it

simply does not belong – a world viewed from an impersonal

vantage-point, made up of publicly demonstrable facts, a world which,

as a matter of principle, needs to treat the single individual’s

perspective as not just as inadequate but even suspect. Asking

what

fictional

literature

can

tell

us about a reality of this kind is

guaranteed to lead us into an impasse for the quite simple reason that

literature is, by its very nature, addressed to a reality of a quite

different kind.

Seldom,

once again, [in continental aesthetics] is the

question addressed in any explicit way, but there

is a constant

underlying suggestion that the reality to which art is addressed is

understood as a political, historical or cultural reality – that is, a

collective reality of some kind.

In

analytic

aesthetics, the debate seeks to link fiction

to a semi-scientific reality, a reality made up of the impersonal,

publicly demonstrable fact. Large

areas of

continental aesthetics, attempt to link literature to a reality which

is just as alien – the world of collective experience which is also, by

its very nature, obliged to transcend the world of the single

individual.

Firstly,

it is crucial to recognise that the concept of

‘reality’, ‘the real world’ etc must not be left in a conceptual limbo

and waved away with cursory phrases such as ‘the world around us’, ‘the

actual world’, ‘the rest of the world in which [aesthetics objects]

exist’, or ‘the great world’.

Secondly, we need to recognise that the reality to which literature –

and all art – is addressed is a reality of a specific kind – which I

have called, in very summary and general terms, the reality of the

living individual, as distinct from the impersonal worlds of science or

history. We need, in short, to

situate literature

in the context in which it rightly belongs and cease seeing it as a

competitor in areas in which it has no essential place.

The real challenge, once having taken those steps, is to develop a

theory of literature and art that builds on this foundation – a theory

based firmly on the recognition that the reality to which art is

addressed is a reality perceived and understood by the single

individual.

It is perfectly possible to develop a theory of literature and art

which is based squarely where it should be and which avoids the

pitfalls I have described. And if

we are to make

real progress – and emerge from our present impasse – that is the

challenge that lies before us.