Goya and the Disasters of War

War has certainly been

part of the “form and

pressure” of recent centuries but

it’s surprising when we reflect on it, how marginal the presence of war

has

often been in the art of those centuries, at least in any obvious

sense. Impressionism

is probably the most famous – or anyway the most popular – art movement

of the so-called

modern period, yet it’s hard even to imagine

a battle scene painted by Monet, Renoir or Pissarro. And Picasso’s Guernica aside, the art of the twentieth

century seems to have been much more preoccupied with harlequins and

everyday

objects than with scenes of war.

The focus in our

conference is not, however, the twentieth century, but the two

centuries

preceding it, and the artist I’d like to talk about is the Spanish

painter and

engraver, Francisco Goya, whose lifetime straddled the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries. Goya’s art is fascinating in itself and he is, I

think,

rightly regarded as one of Europe’s greatest visual artists, but he is

of

particular interest to our conference because his works include some of

the

most powerful depictions of the disastrous human consequences of war in

the history of visual art.

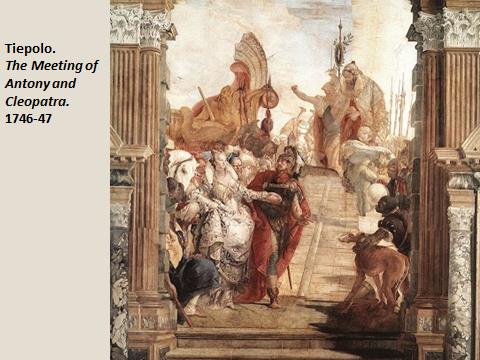

Interestingly

enough, one would never suspect this if one looked only at his earlier

work. Goya

began as a typical artist of the eighteenth century, very much in the

vein of near

contemporaries such as Watteau, Tiepolo, and Fragonard, and the spirit

of his

paintings is, like theirs, a world away from the savage bloodletting of

the

battlefield.

War is almost

invisible in the works of the major artists the eighteenth century.

Admittedly,

it seems a somewhat less bellicose century that its predecessor, that

is, if we

exclude the French revolutionary wars that began in the 1790s; but the

eighteenth

century still had its wars – in both Europe and America – and men were

still

dying on battlefields or fearing they might. But the painters of the

period, like

most of the novelists, incidentally, do not seem to have been

interested.

Watteau invented his enchanting world of fetes

galantes; Tiepolo created a dazzling, theatrical realm full

of fantasy and

brilliance; Boucher

invited his viewer

into a world of voluptuous nymphs and cupids; Canaletto and Guardi

favoured

elegant Venetian scenes or picturesque ruins, and English painters such

as

Gainsborough seldom strayed from tasteful portraits of the titled or

the

well-to-do. Scenes of violence were not unknown, of course: religious

paintings

still depicted the martyrdoms of saints, suitably dramatized, and the

rather idiosyncratic

Magnasco even descended into the dungeons of the Inquisition – though

even here,

in keeping with style of the times, the action seems enveloped in a

veil of

semi-fantasy and, as André Malraux aptly comments, “Magnasco

paints with such verve that his scenes

of violence become a kind

of ballet.”

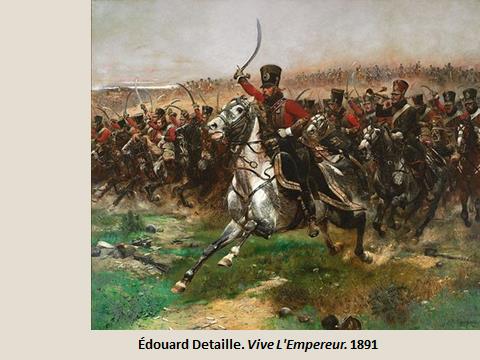

Goya’s nineteenth century

contemporaries were

somewhat different, of course. In the wake of the French Revolution and

the

Napoleonic wars, the world of refined courtly amusements and fetes galantes gave way to rather

sterner subjects, and military exploits were often among them. Salon

painters of

the period, such as Vernet, often preferred what were then called ‘big

subjects’

and battlefield scenes could meet this requirement admirably. The

formula was

fairly straightforward – a blend of military glamour and

semi-photographic realism.

The subject matter should preferably be dramatic and eye-catching – a

cavalry

charge, for example, could do very nicely – and while a certain

quantity of

blood might flow, the emphasis should be on military dash and valour,

not on

the disturbing cruelties of war.[1] There’s is a large painting of this kind in

the Art Gallery of New South Wales, entitled Long

Live the Emperor!

which, although dating from later in the

century, represents the genre quite

well.

There were, of

course, paintings of higher quality than this – such as Gericault’s

well-known Officer of the Chasseurs Commanding a Charge and here the influence

of Romanticism is not far to seek. Seen in this light, war becomes a

magnificent drama, and even when Delacroix shows us the tragic events

of his Massacre

at Chios there is a

mood of lingering heroism, even in

the stricken victims themselves, that keeps the inhumanity of the event

at a

safe distance. All in all, nineteenth century painting tends to muffle

the horrors

of war, or perhaps one should say to infuse war with a kind of poetry –

sometimes of the highest quality, of course – which instinctively

searches out

the dramatic and the heroic rather than the vicious, the atrocious and

the

inhuman. Perhaps a fitting symbol of all this might be Turner’s

well-known

rendering of the Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last Berth. The Temeraire

had been

in the thick of

fighting at Trafalgar but there are no echoes here of the screeches of

wounded

and dying sailors, just the almost Wagnerian grandeur of a gleaming,

Romantic

seascape.

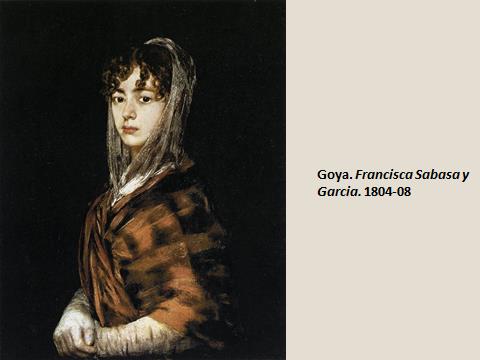

This then is

the world of Goya’s eighteenth and nineteenth century contemporaries.

The early

Goya, as I’ve said, belongs very much to the eighteenth century mood I

described

earlier – the world of fetes galantes

and courtly amusements, and if he had died in his mid-forties – that is

in the

early 1790’s – art history would almost certainly record him as a

painter in the

baroque/rococo style and, taken all in all, a relatively minor one when

seen in

an international context and compared with figures such as Watteau,

Fragonard

or Tiepolo.

However, Goya did not die in his mid-forties;

he died

in 1828 when he was over eighty years old. And at the age of forty-four

he fell

victim to a grave illness that came close to killing him, and left him

stone deaf

for the rest of his life. For Goya, this experience seems to have been

a

descent into a solitary Hell – not in the religious sense because he

seems to

have been indifferent to God, but in the sense of a prolonged, solitary

torment. He emerged from the experience a different person. Outwardly, very had little had changed.

He

resumed the post he had worked hard to acquire as Painter to the

Spanish Court,

and went on to produce numerous portraits of the Spanish royal family

and various

aristocratic patrons, many of which figure among his finest works. But

inwardly

he was a man who had begun to see with different eyes, and who had

discovered a

world whose existence other artists of the period had never suspected.

It’s not

too much to say that another Goya was born – a Goya far removed from

the world

of courtly amusements – so far removed in fact that most of the work of

this

‘subterranean’ Goya, if I may so describe him, remained unknown during

his

lifetime except to a few close friends. And prominent among the themes

that

preoccupied this new, subterranean Goya was the cruelty and

horror of

war.

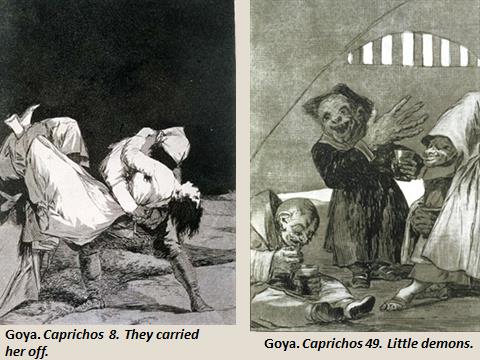

Though not immediately. The first major work

of this new Goya was a series of etchings published in 1797

which he entitled

the Caprichos. Here we suddenly

enter

a world that seems the direct antithesis of everything that centuries

of post-Renaissance

art had aspired to. In subject matter as in style, it is a kind of

anti-world

of what the eighteenth century was by then calling “fine art” – les beaux-arts. For this Goya,

notions

of beauty, refinement, taste, grace, heroism, and nobility vanish

entirely, to

be replaced a world that seems like an evil dream – a dark, leering

world of hypocrisy,

deceit, gluttony, prostitution, rape, witches, and half-human monsters.

The

world of Watteau, Fragonard, and Tiepolo seem to be in

tune with the spirit of the times: they reaffirm the notions

of

sophistication and cultivated taste to which the Age of Reason was so

strongly

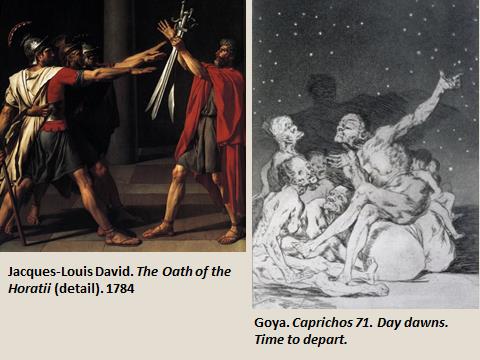

attached. Styles altered somewhat with the slightly later figure of Jacques-Louis David: the elegant and

ornate baroque gave way to a more sober, neo-classical register, but

even David

continues to affirm a hierarchy of values, an ideal of man – which of

course helps

explain why the revolutionaries held him in such high esteem. But there is no

ideal of ‘man’ in the subterranean Goya. Unlike his

contemporaries, he seems

to be in serious conflict with his times, as if pointing to a hidden

fissure in

the civilized surface of the Enlightenment exposing a dark underworld

beneath –

a world in which all the characters seem to be proxies for some

relentless

demon who rules over a world in which the slightest gleam of hope has

been

extinguished.

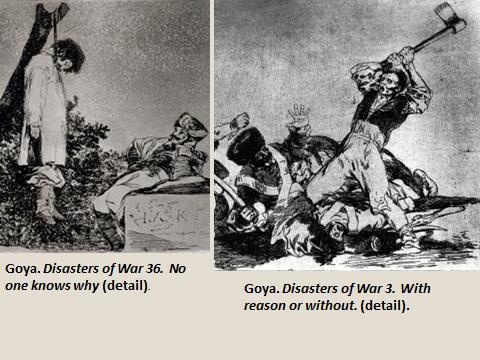

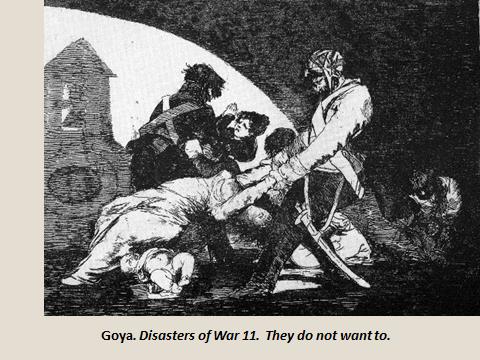

The Caprichos

were initially put on sale, although Goya withdrew them

soon afterwards. His

second series of etchings, completed between 1810 and 1820, was never

advertised

for sale. This was the Disasters of War.

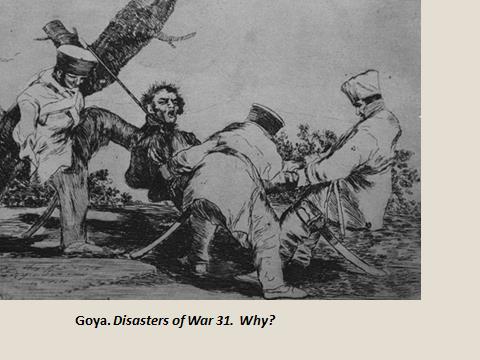

Here, there is no longer any need for proxies for, as Andre Malraux

comments, ‘Goya’s

demons have now found their true form, the horrific’[2] and the Disasters

‘shout

what the earlier

etchings had whispered’.

Or as another writer puts the point: ‘The real world having caught up

with

[Goya’s] imagination, mining its depths becomes superfluous. Why bother

summoning up devils when men’s conduct is already diabolical?’

The war in question was the struggle of

the Spanish people to expel the French invader in the early years of

the

nineteenth century. The conflict was savage, protracted, and punctuated

by

atrocities by both sides – one of the first examples of the kind of

guerrilla

war we have come to know so well, that sweeps up civilian populations

of

men,

women and children. Some critics see the Disasters

as kind of cri de coeur

of Goya

the Spanish patriot against the cruelties of the French occupier but

while

there is no doubt an element of this, Goya’s depiction of war goes much

deeper

than a simple political melodrama of good versus bad. The black irony

of many

of his captions is one sign of this, but there are others as well. The

locations,

for example, always seem rather ill-defined: they might well be Spain

but they

seem strangely divorced from any specific geography. The uniforms of

the

soldiers are only sketchily done as if nationality were only secondary.

And the

perpetrators are not always the French soldiery; they are often Spanish

peasants

as well. In the end, the evil is war itself – or perhaps something

deeper: the

lurking inhuman in man that many Enlightenment thinkers had tried very

hard not

to see.

Goya’s aim is not, however, simply to

depict something ugly and menacing. “A great artist,” André Malraux

reminds us,

“does not depict horror for the sake of horror any more than he depicts

battles

for the sake of battles, or a still life for the sake of still life”.

Indeed,

if it had simply been horror for the sake of it, the Disasters

would be easily outdone by photographs of horrific war

injuries

or even some of the monsters of Hollywood science fiction. Goya’s art

involves

a genuine creative act – the development of a true artistic style in

the sense

the word style assumes when we think of any great painter, novelist or

composer.

What then is the nature of that style? Some commentators, describe Goya

as a

realist but that judgement strikes me as too hasty. The idea of realism

in art

is confused at the best of times: it suggests a kind of neutral style

that somehow

transcribes reality “just as it is” with no artistic interference. But

the

notion of reality “just as it is” is obviously question-begging and

there, is

any case, no such thing as a neutral style – a form of representation

that does

not “render” or “interpret” in some way. Even a photograph has its

share of

style – the style of photographs. Styles we call “realistic” can only

be realistic

inflections of existing styles – as Renaissance art was of the

Byzantine style,

for example. So, is Goya a realist in this sense? Does he simply modify

the

baroque and rococo painting of his times to achieve greater naturalism?

Is he

just a kind of Watteau or Fragonard or Tiepolo made more photographic?

Or a

Jean-Antoine David somehow brought closer to the world of everyday

appearances

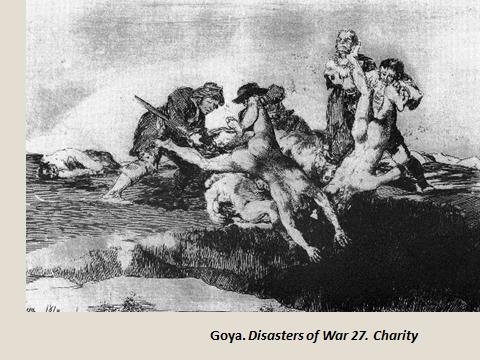

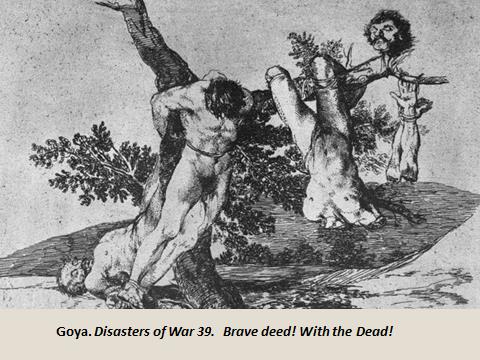

The diagnosis is obviously inadequate. Far

from mere photographic realism, there is a kind of poetry in Goya just

as there

had been in all post-Renaissance art – whose prime objective had never

been

realism despite what art historians often say. But the poetry

of

painting

from Botticelli onwards through painters such as Raphael, Titian,

Watteau and

David, had been in pursuit of what the Elizabethan Sir Philip Sidney

had called

a “golden world” in contrast with Nature’s merely “brazen world” - a

golden

world which, even in its tragic moods, as in Titian’s Entombment

conveyed a sense of nobility. The Disasters

of War, by contrast, are a kind of anti-poetry in search of

an

“underworld” – a dark, sinister, unforgiving realm in which human

suffering has

no purpose and in which notions of nobility and human dignity –

including those

espoused by the Enlightenment writers of the times – are simply a

hypocritical

sham. And war, with its cortege of atrocities, is the unadulterated

essence of

this underworld. It is the context, as Malraux says, in which Goya’s

demons

find their true form.

Not all writers agree with this view, I

should say. Some see a message of hope in the Disasters,

one critic arguing for example that Goya is championing

the heroic struggle of ‘the people in action, the common people,

workers and

peasants” and thus “testifying to “a profound optimism, faith in

reason, and

heroic affirmation of human dignity and freedom”. This is not a view I

share.

The Goya I see is not unlike Ivan Karamazov who finds nothing to

persuade him

that the endless tale of human suffering can possibly have an

underlying,

redeeming purpose. Whatever Goya’s political views about the struggle

against

the French may have been – and initially at least he seems to have

welcomed

their

presence in Spain – the Disasters,

to

my mind are a long way from a political or moral pamphlet about good

versus

evil. If Hamlet believed that that ‘the time is out of joint’, Goya’s

preoccupation is a universe – a

scheme of things – out of joint. Aldous Huxley captures the atmosphere

of the Disasters admirably when he

writes:

There

are those shadowy archways … more sinister than those

even of Piranesi’s Prisons, where women are violated, captives squat in

hopeless stupor, corpses lie rotting, emaciated children starve to

death.

and he goes on:

Of

still more frequent occurrence in the series are the crests

of those naked hillocks on which lie the dead, like so much garbage …

Often the

hillock sprouts a single tree, always low, sometimes maimed by

gun-fire. Upon

its branches are impaled, like the beetles and caterpillars in a

butcher bird’s

larder, whole naked torsos sometimes decapitated, sometimes without

arms…[3]

War in the Disasters

is, in short, something quite different from a struggle

between good and evil. It is a universe in which there is only evil, a universe, as Malraux

comments, from which “God has

departed but in which Satan has remained”.[4]

Theodore Adorno made the oft-quoted

comment that ‘to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric’. Whether or

not that is so, it’s hard not to feel

that the sinister poetry of Goya’s etchings, well before Auschwitz, has

disturbing affinities with the single-minded pursuit of humiliation,

atrocity

and murder we associate with the extermination camps. And although

created at

the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Disasters

of War are disconcertingly suggestive of war as it has

been experienced in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – war with

its wretched

litany of atrocities and mass murders.

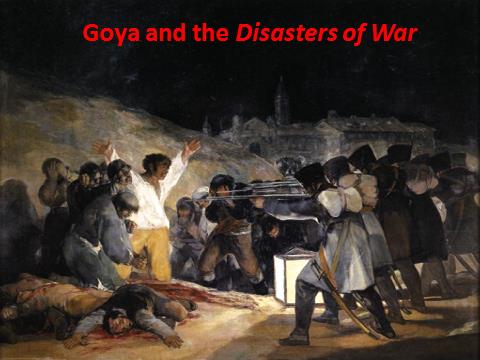

Goya’s famous work The

Third of May, 1808, which is like a scene from the Disasters in paint, is uncannily

suggestive of this modern satanic world of anonymous mass death. Some

critics

suggest that the upwardly extended arms of the central figure remind us

of a

crucifixion but, if so, it is a crucifixion very different from those

that post-Renaissance

European artists were accustomed to depict. There are no mourners here,

only a terrified

crowd apparently waiting their turn to be shot; there

is no dramatic

Titianesque sky telling of the universal significance of the event,

only an

inky blackness that seems to close over the sinister scene like a lid;

there

are no witnesses, only a faceless row of soldiers who seem like an

anonymous

killing machine, with a lifeless ghostly building in the background;

and the

central figure’s gesture of defiance – if that’s what it is – seems

merely to

be mocked by the prone figure in the foreground whose arms are extended

in a

just the same way – but in death. In short if this is a crucifixion, it

is one that

seems to portend despair rather than hope. And this work, we tell

ourselves

with amazement, was painted in the immediate afterglow of the

Enlightenment

when so many thinkers and writers were investing so many hopes in

mankind’s

future.

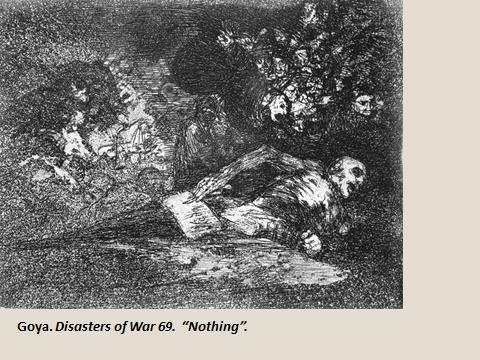

André Malraux describes Goya as ‘our

greatest poet of blood’ and ‘the greatest interpreter of anguish the

West has

ever known’[5] Perhaps the most telling, if most enigmatic,

image of this anguish

occurs towards the end of the Disasters in

Plate 69 which shows a skeletal figure – a casualty of war perhaps? –

scrawling

“Nada” – "nothing” – on a scrap of paper, as shadowy faces loom

nightmarishly out

of the darkness. If the 3rd May 1808

is a crucifixion, perhaps this is the resurrection scene – or anti-resurrection scene – that goes with

it?

Whatever we may think about that

question, one thing at least is beyond doubt:

as a testimony to the horrors of warfare, Goya’s Disasters of War remains without

peer in the history of

Western art.

Huxley, Aldous. "Foreword." In The

Complete Etchings of Goya. New York:

Crown Publishers, 1943.

Malraux,

André. Le

Triangle noir. Paris: Gallimard, 1970.

Malraux,

André. Saturne:

Le Destin, l'art et Goya. Paris: Gallimard, 1978.

Todorov,

Tzvetan. Goya, A L’Ombre des Lumières.

Paris:

Flammarion, 2011.

[1] The

taste for

paintings of this kind evaporated with the advent of the cinema.

[2] André Malraux, Saturne:

Le Destin, l'art et Goya

(Paris: Gallimard, 1978), 98. Tvetan Todorov writes in

a similar vein: ‘The real world having caught up with [Goya’s]

imagination,

mining its depths becomes superfluous. Why bother summoning up devils

when

men’s conduct is already diabolical?’ Tzvetan Todorov, Goya,

A L’Ombre des Lumières (Paris:

Flammarion, 2011), 137.

[3]

Aldous Huxley, "Foreword," in The

Complete Etchings of Goya (New York: Crown Publishers, 1943),

12.

[5] Malraux, Saturne:

Le Destin, l'art et Goya, 133.