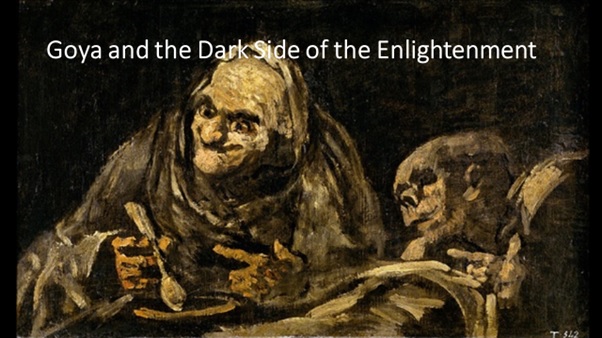

Goya

and the Dark Side of the Enlightenment

The conference program suggests that most of the papers will deal with

aspects of Enlightenment philosophy, including political and social philosophy.

And that’s very much as it should be because the very word Enlightenment

conjures up for us a period of intense philosophical activity – and one that

has left a lasting impression on Western culture.

But alongside philosophy, a lot was also happening at this time in the

field of art– in literature, music and visual art – and although one is

not always immediately aware of it, artists in the eighteenth century were

responding to the same cultural climate as philosophers, and in their own ways

exploring implications of the same currents of thought. So I’m hoping that in

discussing certain developments in eighteenth century art, I might be able to

throw some useful light, even if indirect light, on the conference’s

deliberations on aspects of Enlightenment philosophy.

The artist I’d like to focus on is Spanish painter and etcher, Francisco

Goya. Goya was born in 1746, in modest circumstances in a Spanish provincial

town. He became an apprentice painter at age 14, worked hard at his chosen

profession, and eventually rose to the rank of First Court Painter to the

Spanish monarchy, his long life ending at age eighty in self-imposed exile

across the French border in the city of Bordeaux.

As an artist, Goya is very much a dual personality. On the one hand,

there was the Goya who was an official painter to the Spanish court, who

gradually developed into one of the finest portrait painters in the history of

European art, this work [Senora Sabasa Garcia] providing a good example. But there was another Goya as

well – an artist whose works the Spanish court knew little about, and who

produced a series of etchings and paintings – the latter including his

so-called “black paintings” – which are perhaps the darkest, most despairing

works anywhere in European art. These works, of which Saturn devouring his

children is a relatively well-known example, are the ones I want to focus

on today. Most were not exhibited in public in Goya’s lifetime or placed on

sale; but from the late nineteenth century onwards they gradually began to

reach a wider public and are now considered to be among his most powerful

works. Indeed, for many people, they have almost become synonymous with the

name Goya, giving birth to the adjective “Goyaesque”, a term whose meaning is a

not-too-distant relative of “Kafkaesque”.

Why have I chosen to discuss these works? The short answer is that they

exemplify what I think of as “the dark side of the Enlightenment” – an aspect

of the eighteenth century mood that’s rather different from the sense of

confidence and optimism we often associate with Enlightenment thought. Goya, I

should briefly say, is not the only representative of this dark side. The

numbers are quite small but there is also de Sade, whose Enlightenment zeal

ends up making him an apostle for crime, and whose ideal human society would be

an isolated castle behind whose walls his victims suffer humiliation, torture

and death. And there is also the somewhat lesser-known figure of Choderlos de

Laclos, author of the Les Liaisons dangereuses, a novel

which is sometimes seen as just another work in the 18th century

libertine tradition but which is, in fact, I would argue, a tale of ruthless

psychological oppression built, paradoxically enough, around that

quintessential Enlightenment value – human reason. Goya,

nevertheless – and in particular the Goya of the etchings and black paintings –

is probably the most striking representative of the Enlightenment’s dark side,

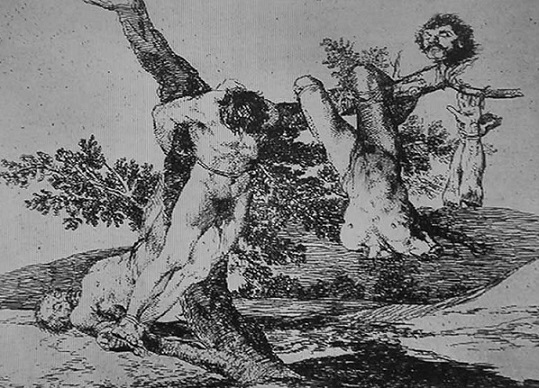

and many of his images – like this one from his series entitled the Disasters

of War – seem to fly directly in the face of

the values we tend to connect with this period of European history. Here,

instead of human dignity, virtue, compassion, tolerance and reason, we find a

nightmare world of brutality, torture and murder – a world that some, with good

reason I think, see as prophetic of twentieth-century total war and the

extermination camps.

How and why did this happen? Why did Goya, an intelligent man of

the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, create images such as these, and

what do they signify? To respond to those questions adequately, I think we need

to take a short step backwards in time to the Renaissance and look at the

issues in a broader context.

Historians of art were once fond of claiming that the revolutionary

stylistic changes in painting and sculpture that took place with the

Renaissance were essentially manifestations of a newfound interest in “realism”

or “naturalism”, an interest sparked by the rediscovery of classical sculpture.

I believe, however, something much more profound was involved. The birth of

“art” in the new sense conferred on the term by the Renaissance was the

consequence not of any sudden urge to represent the world naturalistically but

of the emergence of a new conception of humanity. The Middle Ages had been very

different. The men and women of medieval imagery often strike us, as we might

expect, as the weak and vulnerable inhabitants of a transient here-below,

wholly dependent for their salvation on God’s mercy. But as Christian faith

commenced its slow decline, the distance between man and the deity gradually

closed, and we begin to encounter human figures who seem themselves to

have taken on qualities of the divine – such as the transcendent, dream-like

figures of Botticelli, or the self-possessed, exalted creations of

Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo – figures who seem to be standard bearers of

a brave new world of nobility, harmony and beauty, born of a rapprochement between

man and God.

This was not just a turning-point in art. It was certainly a

turning-point in which art played a crucial role, because it was through

art, above all, that this new image of humanity was made manifest. But in its

essence it was the birth of a new European conception of man and his

possibilities, a conception in which men and women, even in their moments of

struggle and tragedy, seem to cross a threshold into a loftier universe in

which they themselves partake of elements of the divine. In effect, art was

furnishing a new absolute replacing a slowly waning Christian faith – which is

why, of course, the terms “art” and “artist” now assumed an unprecedented

meaning and importance. Artists were now revealing a new form of transcendence,

a new ideal world outside of which, as one critic expresses it, “man did not

fully merit the name man”. Here, I believe, we approach the deeper meaning of

the phrase “Renaissance humanism”: it was not simply an affirmation of the

powers of man but also, and perhaps more importantly, an annexation of certain

of the attributes of God. The medieval world, in which such a thought would

have been sacrilege, has now slipped away – and, as we know, from about Raphael

onwards, all medieval painting and sculpture was viewed with disdain and

referred to, pejoratively, as “Gothic”. Faith in God is now replaced by faith

in man. The saint is replaced by the hero. Man can still stumble and fall, but

even in falling he can reveal his nobility, his spark of the divine. He may be

a tragic hero – as in the plays of Corneille and Racine – but he is

a hero, nonetheless.

Needless to say, this situation was not static. As religious belief

continued to weaken, European civilization’s sense of the divine weakened with

it. By the eighteenth century, which finally witnessed what one writer calls

the “radical abandonment of Christianity”, the sense of transcendence at the

heart of post-Renaissance art was, not surprisingly, greatly weakened as well.

The ideal of harmony and beauty remained firmly in place, but it was brought

closer to the earth, so to speak, where it donned the less imposing costumes of

charm, elegance and delight. Which is why the visual art of the eighteenth

century often reminds us of the theatre. From Watteau’s fêtes galantes,

to costume dramas such as Tiepolo’s Banquet of Cleopatra, painting now

often resembles a world of refined, sociable, good taste, located just “across

the footlights”. By the eighteenth century, as one writer nicely puts it, art

had taken the form of “an ornate image man was making of himself”.

An “ornate image” which had not, however, lost contact with its

Renaissance origins. The Renaissance vision, as we’ve noted, had been

profoundly humanist. In place of the medieval image of man as “fallen

creature”, temporary wayfarer here below, it substituted a vision of man as

heir to a brave new world of nobility, harmony and beauty. The relentlessly

empirical and anti-religious spirit of the eighteenth century reined in these

lofty aspirations and settled for the less heroic ideals of charm, refinement

and good taste, but the underlying confidence in man, the underlying humanist

impulse, was not affected. The semi-theatrical worlds of Watteau and Tiepolo

certainly suggest a form of transcendence markedly less ambitious than those of

Michelangelo and Titian but it is still an affirmation of man – a

celebration of his capacities, and something very different from the humble

medieval acknowledgment that without God’s mercy, man is as nothing. From the

Renaissance onwards, this humanist vision was the sine qua non of art,

and no post-Renaissance artist – no Titian, no Poussin, no Rubens, no Tiepolo,

no Jacques-Louis David – ever conceived the idea of challenging it. In art, as

in the mainstream philosophy of the times, the eighteenth century rested on a

faith in humanity’s possibilities. The Christian religion may have been

radically abandoned, but man, civilized man, the man of virtue and reason was

very much a vision of promise and hope.

Which brings me to Goya, whose etchings and “black paintings”, I want to

argue, represent the very reverse of that promise and that hope. But first let

me provide a little more background. Goya, as I’ve said, lived a long life, and

the works of the first three decades of his career belong wholly to the baroque

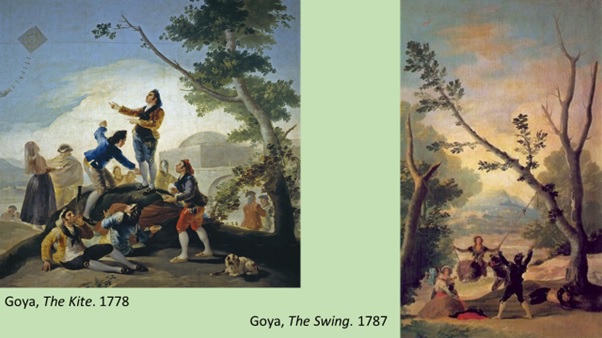

school of refinement and delight I’ve just been describing. Thus, many of the

works he completed over this period, like the two I’m showing now, are imbued

with the same spirit of light-hearted charm one finds in countless works of the

times across the length and breadth of Europe. In late 1792, however, Goya fell

gravely ill and when he recovered he was left with a bitter legacy: he was

stone deaf and would remain so for the rest of his life. Now, I certainly don’t

want to draw a simplistic, one-dimensional link between Goya’s deafness and

what followed and I’ll have a little more to say about that issue later. But

it’s fairly clear, I think, that the event marked the beginning of something

quite new in his art, something much darker and more disturbing than anything

he or any of his predecessors had ever attempted.

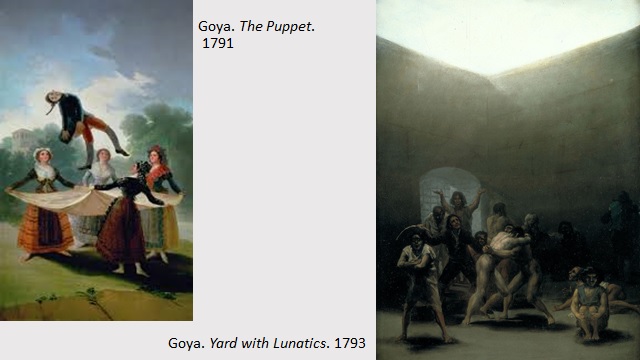

One can see the early signs in the work entitled Yard with Lunatics

that Goya painted during his convalescence; and one has only to compare it with

a work such as The Puppet, completed not long before he fell ill,

to see that something exceptional has taken place. The Puppet

is a fairly conventional exercise in eighteenth century baroque charm; in Yard

with Lunatics, the drab palette and the empty, unprepossessing gestures of

the asylum inmates suggest that any desire to charm is being actively shunned.

This, however, was only a beginning. Goya still had to earn his living

of course and after his recovery he resumed his duties as Court Painter and

went on to become the superb portraitist we saw an example of earlier.

But in the wake of Yard with Lunatics, he also produced a series of

what, for brevity, I will call his “dark works” – a series of etchings and

paintings that replace the beauty and harmony of the post-Renaissance tradition

with a cruel and sinister domain that one critic has aptly described as a world

lit by a “black sun”. I’d like now to show you some examples of these works and

explore what they might represent.

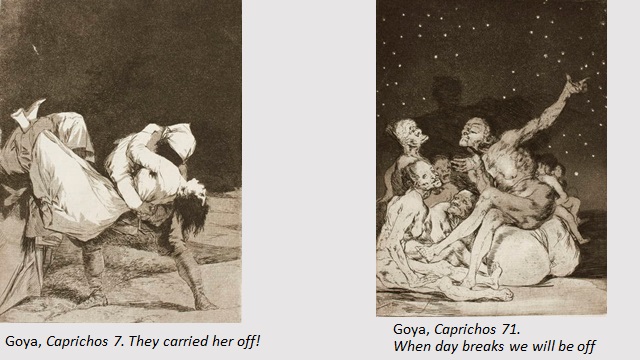

The first series of etchings was called The Caprichos. In the

public mind today, these works are often associated with one particular plate

called The sleep of reason produces monsters, which is number 43 out of

a series of 80 and which is frequently reproduced when the Caprichos are

the topic of discussion. The conventional interpretation of this image is that

if mankind will only listen to the voices of reason, and banish foolish

superstitions, a better, kinder world will then be possible; and this

interpretation is often accompanied by the claim that the image encapsulates

the message of the Caprichos as a whole, and indeed that it captures the

message of all Goya’s etchings, if not his black paintings as well. Goya

is thereby placed securely on the side of the angels and confirmed as a

disciple of humanist Enlightenment ideals. I don’t have time today to provide a

rebuttal of this interpretation of Caprichos 43, but it’s important that

I at least make the point that, despite the impression often created by critics

of this persuasion, the image is not in fact typical of the Caprichos as

a whole and still less of the many other dark works that were to follow.

Pursuing themes that were to become central to these elements of his work, the Caprichos

are principally devoted to scenes of cruelty, suffering, and the shadowy world

of witches, demons and monsters; and their overall significance, as distinct

from the interpretation one might place on a single image taken in isolation,

seems to me to have very little to do with prospects for a better world or the

calm, benevolent voice of reason.

This same is even more obviously true of Goya’s second series of

etchings, the Disasters of War. Here again there are critics who manage

to discover a conventional Enlightenment message, the argument being that Goya

is documenting the consequences of the political blunders that led to the

ill-fated French occupation of Spain in the early 1800s and the guerrilla war

that followed – the consequences, that is, of not listening to the voices of

reason. But as one leafs through the eighty or so etchings, the political

context rapidly takes second place to the sheer force of the images and the

relentless variations on the themes of human savagery and suffering – murder,

rape, torture, starvation, atrocity, epidemic and mass burials. The central

subject, one cannot help but feel, is less a specific war than all war,

from time immemorial, and above all, man’s seemingly limitless capacity for

inhumanity.

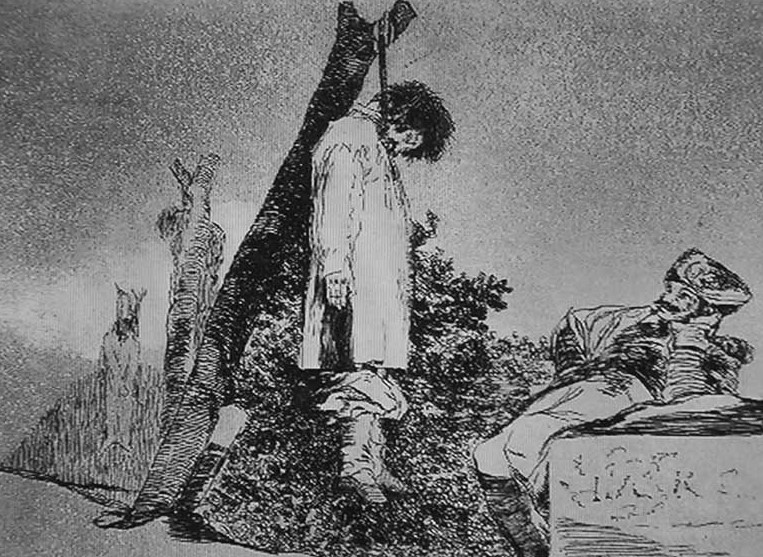

The Disparates, Goya’s final series of etchings, take this sense

of inhumanity a stage further. The Caprichos had borrowed some of their

subject matter from social ills; the Disasters are framed in the

language of war and atrocity; the Disparates often minimise such

“narrative” elements and formulate their indictments in images that seem

somehow to be intrinsically inhuman. So, for example, we encounter the

enigmatic People in Sacks who inhabit some sinister Stygian gloom and

seem inexplicably untroubled by their bizarre form of captivity. And there are

haunting scenes such as Fear, a subject Goya had etched years earlier,

in the Caprichos, but which he now renders with even greater

power; and the almost unbearable Disorder with its two central figures

trapped in a monstrous union while a crowd of grotesque faces looks on. And

choosing just one more of the twenty or so plates in this series, here is Cruelty

which seems to probe the very core of human rage, and the madness that can

accompany it. Critics who see Goya as a spokesmen for Enlightenment ideals like

to see all his etchings, including these, as social satire – some even calling

him a “Spanish Hogarth”. But in images such these, we are, surely, a thousand

miles from anything so straightforward or salutary. One has only to compare one

of Hogarth’s satires – such as A Midnight Modern Conversation – with one

of the images we have just looked at to see how large the disparity is.

Hogarth’s etching, which was one of his most popular, may perhaps raise a

smile; Goya’s surely not. André Malraux calls the Goya of the Disparates

“the greatest interpreter of anguish the West has ever known” and if we set

aside one or two possible contenders in literature, such as Dostoyevsky or

Kafka, it is, I think, difficult not to agree.

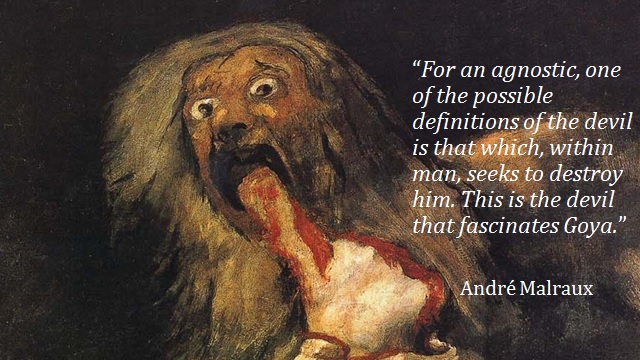

I’ll conclude this rapid survey with a quick look at some of the “black

paintings” as they are conventionally called, and then I’d like to offer some

general observations, linking up with my earlier comments on the Renaissance

and the Enlightenment. Goya painted the images known as the “black paintings”

on the walls of his home on the outskirts of Madrid and they can now be seen in

the Prado. Perhaps most famous of all is Saturn devouring his children,

which we saw earlier. If, to repeat the description I used a short while

ago, Goya’s dark works depict a world lit by a black sun then this perhaps

might be the crazed tyrant of such a desolate realm; and, in any case, one has

only to glance at this work to see that suggestions that Goya’s purpose is

simply social satire seem quite out of the question. The same sense of

desolation pervades the extraordinary Witches Sabbath with its crush of

contorted visages, half-way between mask and human face, the ominous black

silhouette of the he-goat Devil, and the strangely detached female figure on

the right watching on, apparently unmoved. And to choose a not dissimilar work,

here is a detail of Pilgrimage of Saint Isidore showing a press of

macabre faces like visions from a nightmare, or as Wyndham Lewis puts it, “a

gallimaufry of idiotic and ghoulish faces with gibbering mouths”. And finally,

to conclude this little foray into the baleful world of the black paintings,

here is the image I showed earlier on my title slide, called Old People

Eating, [see title slide above] with its two semi-human figures, the head of one strongly

reminiscent of a skull, and both leering as if sharing some unspeakable secret.

We can readily sense the affinity of these images with Yard with Lunatics which

we looked at earlier, but the Goya of the black paintings has ventured much

more deeply into his dark universe. The sinister netherworld he began to

explore in the aftermath of his illness is now

depicted with greater audacity, and one is not in the least surprised that he

made no attempt to place these works on public display.

So much for a quick survey of some of Goya’s dark works. What general

observations might one make? The first and most important, I would argue, is

that these works have resolutely parted company with the world of nobility,

harmony and beauty, with its underlying humanist values, that forms the central

ideal of post-Renaissance art, including the art of the eighteenth century, and

which underpins Enlightenment thought. It is not simply that Goya depicts

misery, cruelty and suffering. The works of painters such as Titian,

Tintoretto, Veronese and Rubens abound in crucifixions, martyrdoms and

entombments, and in tragic events drawn from classical mythology. But as

artists of the time well knew, suffering did not necessarily negate the ideal

they were serving, and could even act as a powerful ally. Suitably portrayed,

suffering and tragedy can readily furnish visions of human grandeur – images of

man’s power to defy obstacles, including death itself, once again revealing his

“spark of the divine”. Thus, for example, Titian’s Entombment transforms

a humble burial into a prodigious event. And, despite having recast the

Renaissance ideal in the form of charm and good taste, even eighteenth century

painting did not entirely lose its fondness for scenes of this kind, especially

in religious art. So there are works such as Tiepolo’s St. Agatha who,

despite her amputated breasts, becomes the heroine of a magnificent stage-play,

eyes cast piteously to Heaven.

Goya’s relentless litany of suffering and cruelty is, however, a very

different matter, and one has only to compare these two works by Titian and

Tiepolo with Goya’s renditions of similar subjects to see the contrast. Goya’s

world contains no trace of nobility and certainly no sign of refinement or good

taste. The regions he is exploring are

unlike anything post-Renaissance art had ever known: in place of nobility there

is nothing but degradation, and the word “beauty” could only be pronounced with

a sneer. The cumulative effect is like an

indictment of the human race, as if man were a mere pestilence on the face of

the earth, a creature fit only to be victim or executioner. The humanist

impulse that had impelled art since the Renaissance and which persisted throughout

the eighteenth century has entirely vanished. No longer capable of challenging

fate despite suffering and death, humanity is now in a state of permanent

bondage – fate’s perpetual slave. Hence the absence of the least suggestion of

human grandeur in these works, and the disturbing impression left by many of

them that the beings who inhabit this ignoble world somehow belong there

– that they are not citizens of some higher, better world who, Dante-like, have

stumbled by mischance into an infernal region, but that they are somehow part

of this netherworld, connive at it, and know nothing better. Varied as

Goya’s etchings and black paintings are, one critic writes, all are ruled by

“the unity of the prison house” – not a capacity to transcend the sorry scheme

of things but a pervasive “feeling of dependence”.

This, I should stress, is not only a question of subject matter; it is

also a question of style. I won’t have time to explore this aspect of Goya’s

dark works but I will make one general point. As mentioned earlier, the brave

new world of Renaissance art was never simply a matter of the realistic

depiction of beautiful objects. Beauty in the Renaissance tradition was always

beauty in a specific sense: it was the beauty of a certain kind of

harmonious, transcendent world and dependent as much on style as on subject

matter. Veronese’s Venus and Adonis, for example, is not merely a tableau

vivant featuring a handsome man and a beautiful woman as actors; it is a

triumph of a certain kind of style – a style capable of evoking a

particular kind of resplendent, harmonious world. Similarly, the dark universe

Goya portrays in his etchings and black paintings involves something very

different from naturalistic portrayals of people or objects conventionally regarded

as ugly or menacing. And, indeed, if it were nothing more than that, these

works would doubtless be comprehensively outclassed today by close-up

photographs of horrific facial injuries or perhaps some of Hollywood’s

digitally-created science-fiction monsters. I stress this point because art

historians often apply the notion of realism to Goya’s etchings and black

paintings and in doing so, I believe, lead us astray. If Goya’s sinister

underworld were to rival the Renaissance tradition and achieve the power of art,

it could no more be a catalogue of “true-to-life” horrors than that tradition

could be naturalistic renditions of beautiful things. Goya, in other words,

required an equivalent of the styles of the post-Renaissance world, but

something quite different – in a sense, the reverse. Goya became the Goya of

the dark works only when he challenged the Renaissance tradition not with bare

“reality”, but with a radically different style, a style of equal power but of

a fundamentally different kind. And one has only to compare, say, the Witches’

Sabbath with works by Goya’s contemporaries, such as David, to see how radical that

difference can be. In whatever form they take, post-Renaissance styles express

a harmony between humanity and the universe. Goya’s dark works with their

tense, abrasive lines and their severe palettes express disharmony, anxiety –

man at odds with himself and the world he inhabits. We are confronted, I would

argue, with an anti-Renaissance art. Goya has broken with a tradition

nearly four centuries old and created a world devoid of all trace of the

humanist impulse at the heart of the post-Renaissance tradition and of the

Enlightenment.

Why did Goya’s illness trigger this step? I think we can make a

reasonable guess. Illness and deafness gave Goya a glimpse of the irremediable

– the realm in which humanity is without hope, where the blind, merciless

workings of fate have won a definitive victory and human existence is reduced

to nothing but suffering and humiliation. Goya the person seems to have borne

this glimpse of Hell with fortitude because he managed to resume his career and

live with his deafness. But Goya the painter was faced with a choice: he could

continue to work solely within the glorious tradition he knew so well, the

tradition in which man, even in his darkest hours – even when hanging on a

cross – can be transfigured and partake of a world of transcendent harmony and

beauty; or he could acknowledge that the desperate world into which he had

descended during his illness was equally real and that, seen in that light,

the glorious tradition – the tradition that eighteenth century art and

philosophy were continuing to express – was a hollow deception, a lie.

Certainly, this illustrious tradition had been the well-spring of countless

splendid achievements, and in his role as Court painter and portraitist, Goya

never forgot them; but it had nothing to say about the world into which he had

stumbled, in which man is simply victim, in which dreams of transcendence,

especially those expressed in the elegant, decorative art of his

contemporaries, seem like childish delusions. Goya could choose to ignore this

inhuman netherworld or he could admit its existence and attempt to discover if

art was capable of exploring it and translating it into the language of

painting and etching. He took up the challenge, and his dark works, I would

argue, are the result.

Let me close with a comparison which I think might throw some useful

light on what I’ve been saying. In his Philosophical Letters, Voltaire expresses

his irritation at the metaphysical anxieties that pervade Pascal’s Pensées –

anxieties encapsulated in Pascal’s famous “image of the human condition”

represented, as you doubtless know, as “a number of men in chains, all

condemned to death, some of whom are butchered each day in the sight of the

others”, while those remaining “see their own condition in that of their

fellows, and looking at each other with grief and despair, await their turn”.

Voltaire roundly rejects this account of human existence. Assessed by the

standards of reasonable men, he argues, the world in which we find ourselves is

one in which men are as happy as nature intended them to be, and where “like

animals and plants, [they] are meant to grow, live a certain time, produce progeny,

and then die”. This being so, he writes, we should learn to be grateful for

what we have. “Instead of being astonished, and full of complaints about our

woes and the brevity of life, we should be surprised and delighted by our

happiness and how long it lasts”.

These two positions are obviously a long way apart. At its heart, I

would argue, Voltaire’s reaction reaffirms the reconciliation between man and

God that began with the Renaissance, and a reconciliation now so complete that

God is almost an afterthought, and man simply lives out his life in harmony

with creation. Pascal’s “human condition” by contrast implies a profound

disharmony between humanity and the universe, a disharmony that can only be

borne through faith in God. Voltaire’s man belongs in the world: he is

created for it and it for him. Pascal’s world is a place of anxiety, and

suffering, humanity’s only succour lying in God’s grace.

There is little doubt, it seems to me, that Goya’s sympathies would lie

with Pascal. Not, of course, that Goya showed any inclination to seek solace in

Christian faith but the etchings and black paintings, as I have suggested, are

in no sense a testimony to an ordered universe in which men and women are as

happy as nature intended. Indeed, some of the dark works, like the well-known 3rd`May

1808, might almost be illustrations of Pascal “image of the human

condition” both in subject matter and the unmistakeable atmosphere of terror

and despair. Viewed in this perspective, the Enlightenment can only be a pretence,

a determination to avert one’s eyes from the scandal of human suffering and the

sinister mystery of human cruelty. Unlike Pascal, Goya finds no solution to the

scandal or the mystery but he nonetheless refuses to avert his eyes.

Which is doubtless why some have seen Goya’s dark works as prophetic of

much of the history of the last century or so. It is not hard, I think, to see

an affinity between Goya’s netherworld and the twentieth-century nightmare of

extermination camps and total war – certainly a stronger affinity than there

seems to be between that twentieth-century nightmare and the eighteenth century

ideal of civilized, rational man and human dignity. If Enlightenment thinkers

believed that Satan had been consigned to the scrapyard of religious superstition,

Goya’s etchings and black paintings suggest that the powers of darkness are not

so easily put down. For an agnostic, writes André Malraux, “One of the possible

definitions of the devil is that which, within man, seeks to destroy him”,

adding, “it is that devil that fascinates Goya”. Goya’s dark works, I believe,

are the consequence of that fascination. The question they pose is whether,

despite the reassuring voices of the Renaissance and the Age of Reason, there

may be a subterranean instinct for evil lurking in the human heart, an obscure,

age-old realm of bloodlust and destruction – the realm of the eternal Saturn.

This is a paper I delivered at a conference entitled Rethinking the Enlightenment held at Deakin University, Melbourne, on 16-17 December 2015. The images are a selection of those I showed to illustrate the paper.

Goya, Old People

Eating

Goya,

Senora Sabasa Garcia. 1806

Goya.

Disasters of War, Plate 37 – This is worse

Bourges

Cathedral, The Damned consigned to Hell

Michelangelo

The Libyan Sibyl, Sistine Chapel 1510

Tiepolo, The Banquet of Cleopatra. 1744

Goya,

Disasters of War, 39 – Heroic feat! With dead men!

Goya,

Disasters of War, 39 – Heroic feat! With dead men!

Goya,

Disparates 8, People in sacks

Goya, Disparates 8, Peopl in sacks

Goya,

Disparates 6, Cruelty

Goya,

Pilgrimage of St Isidore

Titian, The Entombment. 1559

Veronese, Venus and Adonis. 1580

Goya, Disasters of War 36, One can't tell why.

Goya, The Third of May 1808

Goya, Saturn devouring

his children (detail)