Art and the Metaphysical: A Challenge to Aesthetic Orthodoxy

Essentially I’d like to do two things in

this paper: As my title suggests, I want to issue a challenge to

orthodox

aesthetics – by which I mean the aesthetics tradition stemming from the

Enlightenment

with its cluster of ideas connecting art with the beautiful, aesthetic

pleasure, taste etc. And, in addition, I want to suggest that the

fundamental

impulse of art is linked to something that Enlightenment thinkers were

almost

viscerally opposed to – the metaphysical impulse that also lies at the

heart of

religious feeling. That’s a lot to do in thirty minutes so my treatment

of the issues

will necessarily be rather brief; but we can of course explore them

further in later

discussion.

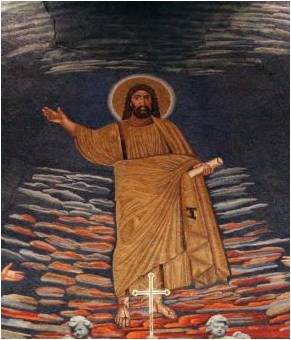

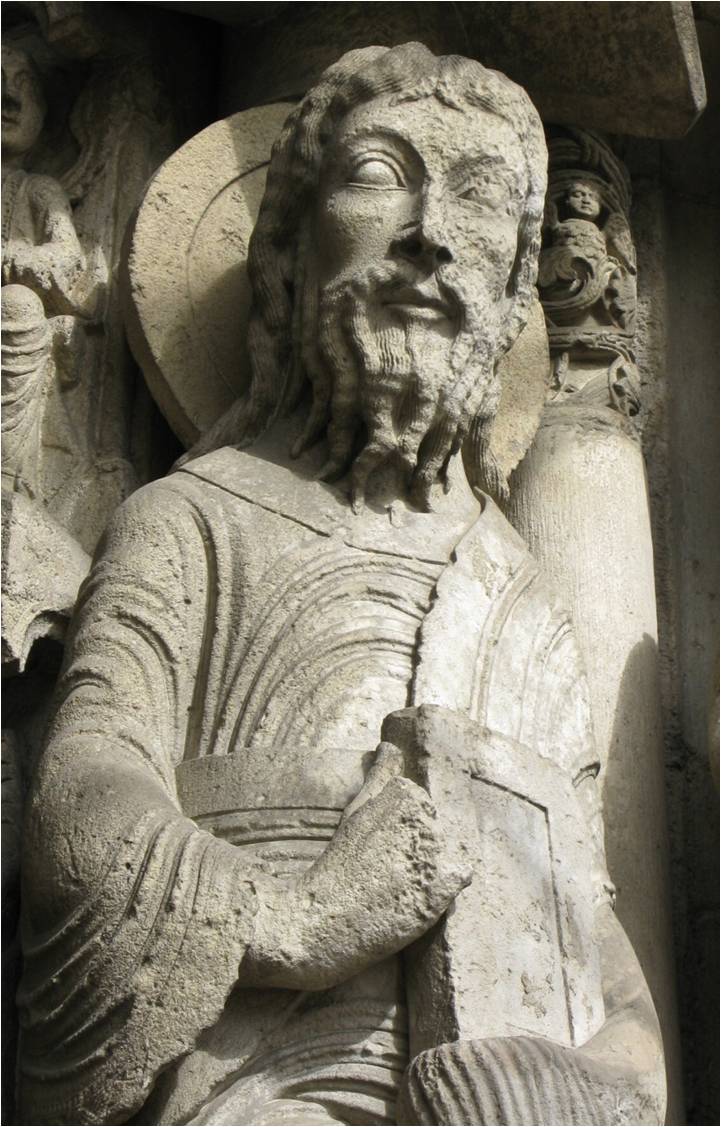

I’d like to begin with a short foray into a realm that modern aesthetics, strange to say, tends to shy away from – the history of art; and I want to begin prior to the Renaissance – in the Byzantine period. Throughout the thousand years of Byzantine civilization, art was certainly not associated with the idea of beauty, and one good reason for this was that there was no such thing as “art” anyway. There was painting and sculpture of course – lots of it; but Byzantine religious images were not made to consort with others of different styles in art museums – institutions then unheard of – but for one context only: the candle-lit interiors of Christian basilicas where, for the assembled faithful, they evoked the mysterious presence of a transcendent, loving God. These images certainly sought to evoke another world, but it was not a world of “art” – a notion about which I shall have more to say. It was the world of a revealed Truth, a supramundane realm quite distinct from the domain of transitory, human concerns here below. The notion of art was as foreign to Byzantium as it was to ancient Egypt, Pre-Columbian Mexico, Africa and a host of other cultures, including Romanesque and Medieval Europe as well.

Now, during the thirteenth century, as the nature of Christian faith gradually altered, the Byzantine concept of the function of painting and sculpture underwent a profound transformation. Eventually, through a process I’ll need to describe fairly rapidly, something that came to be called “art” – or sometimes “fine art” – came into being, with consequences that were to endure for several centuries.

In the field of painting, the decisive change took place with Giotto. Byzantine Christianity had been strongly dualistic: God was love, but He was sacred love, beyond the reach of human comprehension. Giotto’s frescos initiate a reconciliation – a rapprochement – between man and God. They depict sacred events that, unlike those of Byzantium, have become scenes in the life of Jesus. Giotto, as André Malraux writes “[brought] the divine onto a plane nearer to man” by replacing the hieratic forms of Byzantine art with a “solemn expression of the Christian drama”. And in depicting such dramas, he also revealed the possibilities of a painting of a quite different kind – something one might term “pictorial fiction”, or the realm of “the imaginary”.

Malraux makes the point this way: “It was not that religious feelings had disappeared”, he writes,

but that these were complemented by the discovery of an imaginary realm conveyed to the spectator by a power of the artist, distinct from his power of representing scenes from Scripture in that it no longer calls forth veneration, but … admiration.

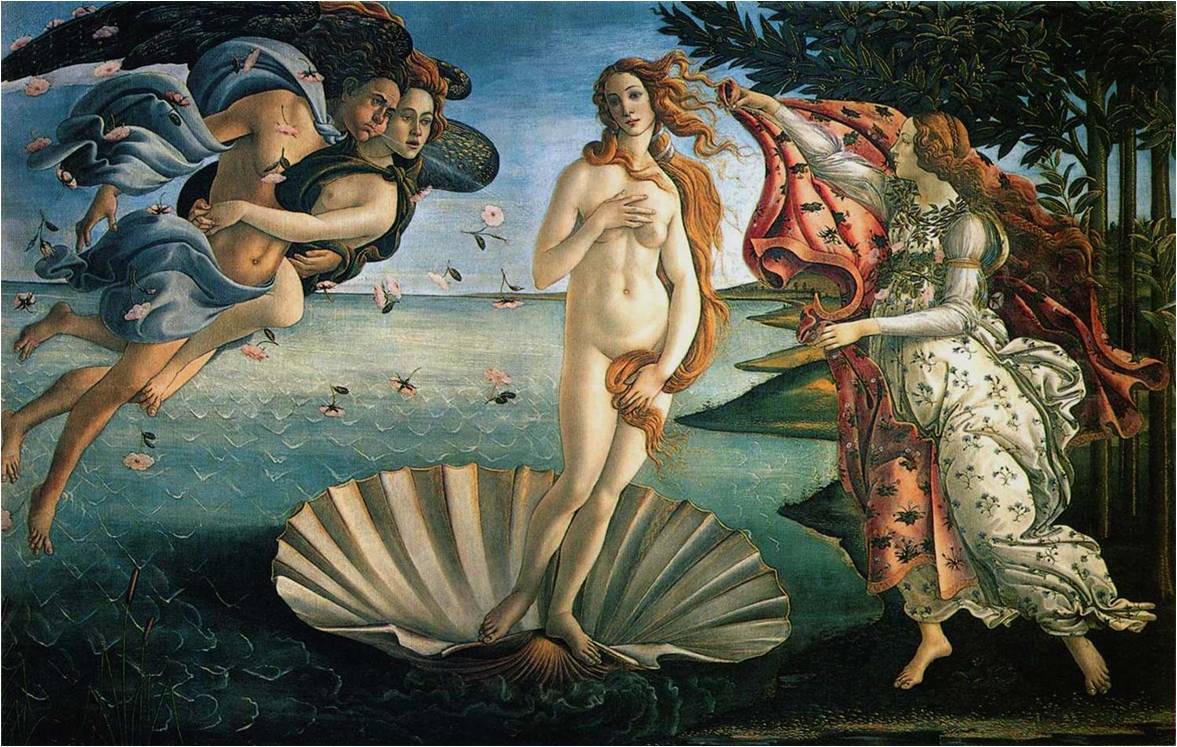

So by the time of Botticelli in the fifteenth century, and then with later figures such as Raphael, Michelangelo and Leonardo, there emerged the first unambiguous depiction of a transcendent world independent of any religious absolute, and reliant solely on the artist’s achievement – an exalted, fictional realm of nobility, harmony and beauty that came into being, elicited admiration, and commanded authority, solely through the power of the work itself. Byzantium was able, if it wished, to worship God without the aid of images – and the iconoclasts, of course, insisted it should; but the new transcendent world of beauty could not be experienced without the Raphaels, Titians, and Tintorettos which were its one and only way of coming into being.

Thus began, in Europe, the reign of “art”. The painted image or the sculpted figure ceased to be objects of veneration, as they had been for Byzantium and Medieval Europe, and became instead objects of admiration. The aim of such works was not, as histories of art often suggest, a more exact imitation of appearances – so-called “naturalism” (although this played an ancillary role); it was the creation of a world of God and man reconciled, a world in which man himself seems touched by a spark of the divine, a transcendent world of nobility, harmony and beauty.

Now, this concept of art endured until the late nineteenth century when a further major transformation occurred which I will discuss later on. For the moment, however, I want to pause in the eighteenth century – a period of major interest for the purposes of my argument, as you’ll see. The concept of art I’ve described remained solidly in place during the eighteenth century but with a subtle modification. The transcendent world of art, as I have said, was not dependent on religious belief, but until the eighteenth century it had often been closely allied to it: its subjects were frequently religious, the kings it glorified ruled by divine right, and the majesty of kings and their retinues partook, even if obscurely, of the majesty of God. Now, not surprisingly, this alliance was severely shaken by the collapse of religious belief that accompanied the Enlightenment, and “fine art”, as it was now often called, required a modified, less exalted, sense of transcendence. The solution was the world of brilliant make-believe we associate with the baroque. There was no question of abandoning the pursuit of a world of transcendent beauty, and of course, when called upon, baroque artists still very happy to paint religious subjects or portraits of kings. But the transcendent was brought "closer to the earth", so to speak, and baroque art became much less a vision of kingly power and authority than a world of which the paintings of Tiepolo or Watteau are emblematic – a semi-theatrical world of elegance, delight, and volupté. The artist’s aim now was less to glorify than to charm, less to praise than to please, and less to serve an ideal of majesty than to satisfy certain criteria of cultured refinement that crystallised around the notion of “taste”.

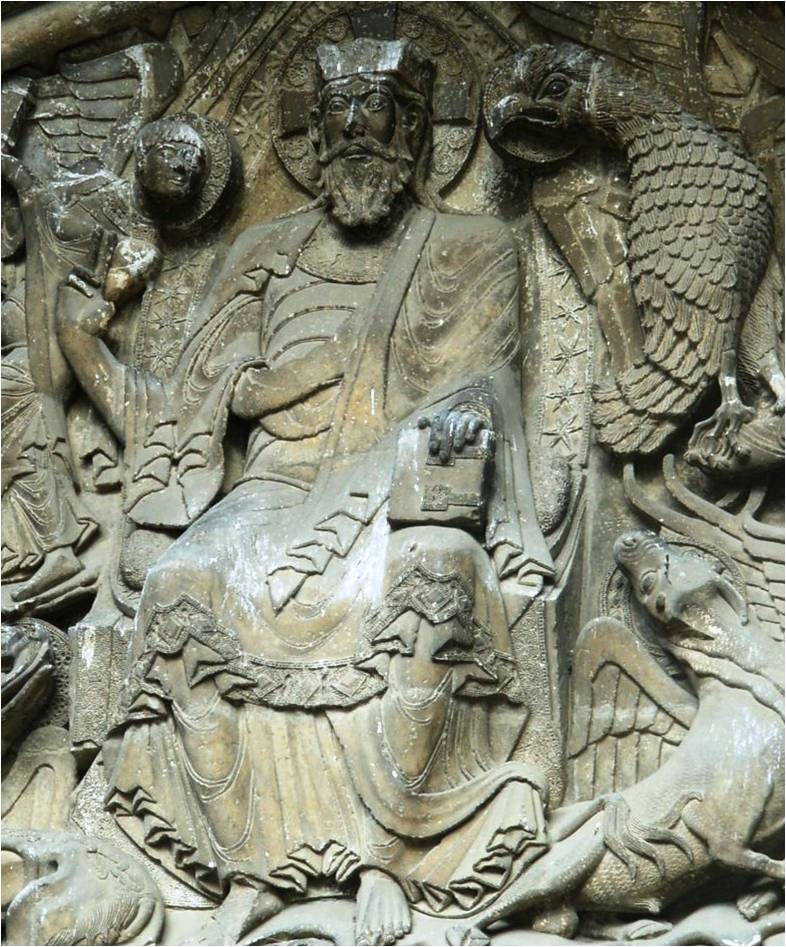

Now, as we know, it was just at this point in history that the new discipline of aesthetics began to take form. And it’s easy – is it not? – to see the connections. The key notions in eighteenth century thinking about painting and sculpture were: fine art, beauty, pleasure, and taste – and taste, of course, brings with it the idea of discernment and judgement. And the key notions adopted by the new discipline of aesthetics were, once again, fine art, beauty, pleasure, taste – and, of course, judgement. Aesthetics, in other words, based itself squarely on prevailing baroque ideas about “fine art”. The link between art and beauty was taken for granted. The notion of pleasure became central – to be rechristened “aesthetic pleasure” and extended to natural beauty as well. And linked to the notion of judgement, the idea of taste was elevated to the status of a major philosophical issue, a key idea in Hume’s aesthetics, and in Kant’s Critique of Judgement, for example. In short, the key concepts of Enlightenment aesthetics – concepts which of course continue to dominate aesthetics to the present day – were concepts that reflected the specific values and the aspirations of post-Renaissance “fine art” in the form they had assumed by the eighteenth century. They were ideas that would certainly have bewildered Giotto who would no doubt have been apalled by the suggestion that his solemn images of St Francis in the basilica at Assisi were merely objects of pleasure designed to appeal to something called artistic “taste”. (1) And Byzantium and Romanesque Europe would doubtless have been dumbfounded. As André Malraux commented in an interview towards the end of his life,

The man who made a great Romanesque statue, made it so that it could be prayed to. If someone had said, “It’s not there to be prayed to,” Saint Bernard, for example, would have replied: “Well, my friend, what’s the good of your sculpture then?” It was sculpture in the service of the soul.

So

why

this

attitude?

Why

is there such a dogged refusal to treat the historical

evidence seriously?

One reason, I think, is that modern aesthetics, especially aesthetics

of the

Anglo-American “analytic” variety, tends to treat art as a timeless,

universal

category and therefore shows little interest in art history and

questions of

historical change. And, of course, avoiding history is a very good way

of

avoiding any disconcerting evidence it might happen to throw up.

But

I

think

there’s

another

objection which goes something like this: “You say that many

objects we

call art were originally created as images of gods. But how could one

thing

change into another? Surely, these objects were what we call art all

along, but

in their cultures of origin this aspect of them was just not

appreciated or understood.”

This

can

be

a

seductive

argument – it must be, because large numbers have been seduced by it.

But I’m going

to spend what remains of my time neutralising it by proposing a very

different

way of understanding the notion of art. Specifically, I want to talk

about art

in metaphysical terms, or to put that another way, I want to talk about

the similarity

between art and the impulse that lies behind religious feeling – an

aspect that

I hope might be of particular interest to this conference. The account

I’m

going to give is based on the thinking of the French art theorist,

André

Malraux, though, once again, time constraints require me to keep my

explanation

fairly brief.

One useful way of approaching Malraux’s theory of art is to contrast it with the popular view that the function of art is essentially to “represent the world”. This theory, which enjoys a large following among writers in aesthetics, raises a number of serious problems, such as how one might accommodate music, which mostly doesn’t seem to represent anything. But I will let those issues pass because my aim here is not to critique this theory but to contrast it with Malraux’s position.

Malraux fully accepts that art often makes use of representation as part of its armoury of techniques, but he rejects the notion that art is essentially representation. What then is his position?

One can give an approximate answer through a comparison with religious experience. Religions, it is commonly said, reject the world of fleeting, everyday concerns for “another world” – a world of a deeper, lasting Truth. For the Christian, the world of the everyday is the “here-below” – the transitory domain which the true believer endures with patience in expectation of another, better world of everlasting Truth. Similarly, for the Hindu or the Buddhist, the world of the everyday is the anarchic world of fleeting appearances, the illusory domain of maya, which obscures the deeper reality of enlightenment. Now, Malraux’s thinking about art bears some resemblance to this. Not that he suggests that art and religion are the same, and his theory of art draws a clear, unambiguous distinction between the two. He argues, nonetheless, that, like religion, art (whether visual art, literature or music) has its origins in a fundamental urge to overcome the chaotic world of fleeting appearances. Art achieves this, he argues, by creating another, rival world which replaces chaos with meaning and coherence. “All artistic styles”, he writes in a key statement,

are significations … always we see them replacing the unknown scheme of things by the coherence they impose on all they “represent”. However complex, however lawless an art may seem to be – even the art of a Van Gogh or a Rimbaud – it stands for unity as against the chaos of mere, given reality.

Now, some philosophers, especially those of the cautious “analytic” cast of mind can get uneasy when one talks about other worlds. They feel, I think, that they know what this world is like, but the idea of “other worlds” sound very suspicious – like something one might read about in the “new age” section of a bookshop. Personally I don’t have much confidence that we even know what “this world” is, so perhaps I am even more cautious than said analytic philosophers. Nevertheless, to reassure any who might worry about the idea of “other worlds” in relation to art, let’s remember that it has a very concrete, down-to-earth aspect that even an analytic philosopher can probably relate to.

For as André Malraux points out, art of any kind always involves a process of reduction – a transformation of one kind of world into another. The painter, for example, is obliged to reduce a three dimensional world to two dimensions; the sculptor transforms a world of movement into a world of immobility, and so on. Malraux is not, of course, claiming that the mere fact of reduction results in a work of art. Reduction he writes, is “the beginning” of art: just the sine qua non. But it does nonetheless result in the creation of another world – a world different in kind from the one in which we live and move.

This might, I hope, help placate those who get edgy at the idea of another world. But I want now to take these thoughts a little further and, in doing so, return for a moment to the comparison with religion. Both art and religion, Malraux argues, seek to replace the chaotic world of fleeting appearances – “the unknown scheme of things”, as he calls it – with another world – a “better” world, in a very general sense of that word. They do this in different ways: religion through the revelation of a permanent Truth – the disclosure of the enduring nature of things, and art, Malraux argues, through creating objects such as paintings or sculpture that impose coherence on the ‘”the unknown scheme of things”, objects which as he says elsewhere, create a rival, unified world “scaled to man’s measure”.

Now there is a lot more to be said about these ideas and I’m painfully aware that all this is very sketchy. But I’m hoping I’ve said enough now to make the basic points I need for the rest of my argument.

For the essence of the matter is this: If we accept that the fundamental impulse behind what we today call art is an urge to create another world – a world that is rival to, and better than, the chaotic world of fleeting appearance – then that creative act might be harnessed to a range of possible ends and will not necessarily have manifested itself in something its contemporaries called "art".

Let’s go back to what I was saying about Byzantine painting, for instance. Byzantine religious images, as I pointed out, were not intended for art museums but to evoke the presence of God in Christian basilicas. These images certainly sought to evoke another world – that is, they were a manifestation of the same basic urge I have been describing – but it was not a world of “fine art”. That is, those images did not fulfil the purpose fulfilled later by the works of Botticelli, Raphael, Veronese, and so on – the creation of a transcendent world of harmony and beauty. And the same is true of the many other cultures, such as ancient Egypt or Buddhist India, in which religion, and a deep sense of the sacred, played a central role. These cultures were not by no means lacking in sculpture and painting but the other world these works pursued had nothing to do with what came to be understood as “fine art” in Renaissance Europe. It was a sacred other world, closely tied to a religious belief.

The notion of “art” arose, as we saw, when religious belief began to fade, when there was a far weaker sense of religious transcendence, and painting and sculpture themselves invented a substitute – a fictional world of transcendent beauty dependent on the creative powers of the artist himself. This was “art” – but it was the first time. That is, it was the first time the fundamental urge to create another, better world did not operate via the manifestation of a pre-existing sense transcendence, but instead created that sense of transcendence itself.

To avoid misunderstandings, I should stress, that there is no suggestion of a kind progress here. I am not for a moment implying that the art that gradually emerged from Giotto onwards, through Raphael, Leonardo etc, was superior in some way to religious works such as those of Byzantium or Egypt. But I am suggesting that the urge to create what Malraux terms create a rival, unified world “scaled to man’s measure” can take a range of forms and express itself in many ways. In the West, from the Renaissance onwards, it expressed itself in what came to be known as “fine art”. Elsewhere – in Egypt, Africa, India, the Pacific islands, and so on – things did not take this course. “Art” is a specifically European creation, a form of the urge to create a rival world specific to Europe (at least at its origins). It produced a series of creative geniuses such as Titian, Rembrandt, and so on; but in other cultures the same the urge to create a rival world also produced creative geniuses; their efforts were simply directed to other ends.

Now, some of you might be thinking, quite reasonably, that even if all this is so, it still doesn’t explain why we today look on so many of the works of other cultures as works of art. If they were created as images of gods, not as art, why do we today see them as art? Why is the statue of an Egyptian Pharaoh, which originally functioned as his “double” to which offerings were made, found today in one of our art museums?

I will need to answer this question very briefly because my time has nearly expired.

I said a moment ago that the urge to create a rival, unified world “scaled to man’s measure” can take a range of forms. One of those forms was fine art’s world of transcendent beauty which I have discussed. But while we today still retain the word “art” – and some people still even continue to use the phrase “fine art” – the meaning of the word has changed radically and it’s important to see how.

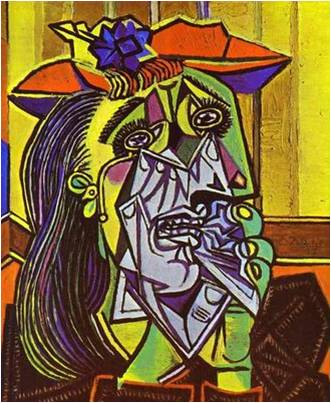

The extinction of religious belief that took place in the eighteenth century brought with it, for better or worse, an extinction of belief in transcendent worlds of any kind, and art itself underwent a profound transformation as a result. The last manifestations of the art in its post-Renaissance sense can be seen in painters such as Delacroix and Turner who were still striving to keep this vision alive; but from painters like Manet and Cezanne onwards, and very obviously in someone like Picasso, the game was up. Art ceased to be a search for a world of transcendent beauty and became something else. What exactly? Art, Malraux argues, fell back simply on its fundamental power – its power to create another world. Isolated from any transcendent value, even a form of transcendence it might create itself, art began to rely simply on its basic aspiration which, in Malraux’s words, “is the age-old urge to create an autonomous world” but which now, “for the first time, has become the artist’s sole aim”.

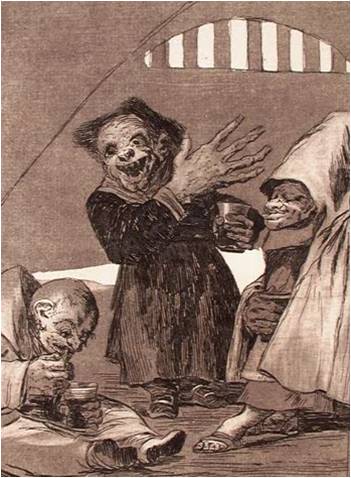

This helps us understand a number of

things. It explains, for example, why so much modern art seems to have

abandoned

any search for the “beautiful” in the sense I’ve discussed. And at the

same

time, our modern sensibility has been awakened for the first time to painting and

sculpture that

the post-Renaissance centuries regarded with disdain because

it did not aspire to their world of

transcendent

beauty. So, for us today, art includes Goya’s Disasters of War

or the Crucified Christ in the Isenheim

Altarpiece and medieval sculpture – all of

which, under the notion of “fine art” that operated from Raphael

onwards, were

consigned to oblivion. And at the same time, our eyes have been opened

to a

wide range of works from non-European cultures, such as Africa and the

Pacific

islands, which, until a century ago, were systematically excluded from

the

ranks of art.

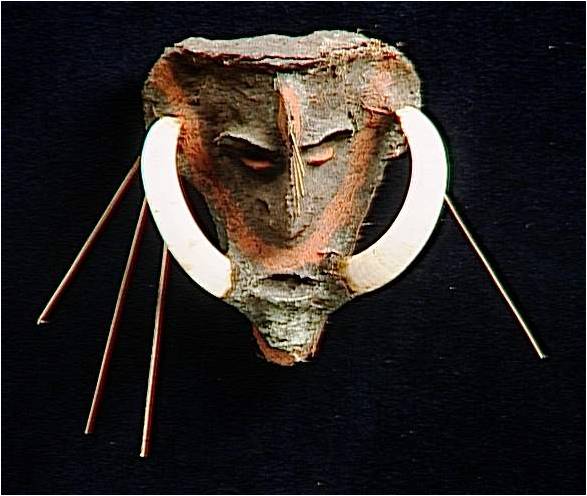

What exactly are we admiring in cases such as these? It seems absurd to say we are admiring beauty! That explanation – so dear to the traditional aesthetics, and so “eighteenth century” in its resonances – seems out of the question here. We have certainly not excluded works founded on a pursuit of beauty from our world of art: we admire Titian and Watteau as well as works such as these. But if Malraux is correct, the quality we find in both a Titian and in works such as these is the fundamental power to create a coherent world standing in opposition to the world of fleeting appearances. We know that many of these objects were created with religious purposes in mind – purposes that we often barely understand. But they nonetheless embody a power to create a rival, unified world, and this is enough to bring them within ambit of the new world of art that has come into being over the past hundred or so years. Here we see the answer to the objection I mentioned earlier – the argument that one thing – a god, for example – could not change into another, and become art. A god can certainly become art when the notion of art in question is sensitive to the power that originally enabled the image of that god to evoke the presence of another world. And our modern notion of art is sensitive to precisely that power. Thus, unlike much modern aesthetics, we are spared the embarrassment of having to turn our back on historical evidence. We know that the god was not “art” in the culture from which it came; but we can explain why it is art for us today.

I have not left myself enough time for a proper summing up so I’ll just end with a brief word in place of it. The idea that art equals beauty, plus associated notions such as aesthetic pleasure, aesthetic judgement and taste, has left a deep imprint on Western thought since the Enlightenment. It has found its way in various guises into the works of thinkers as various as Hutcheson, Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, and Heidegger; and it continues to have modern defenders in people such as Roger Scruton, Elaine Scarry, Arthur Danto, and even, to my surprise recently, Jean-Luc Nancy in France. Whether or not the idea of beauty plays a legitimate role within the systems of thought of these different figures is not a matter I wish to pronounce on – or need to pronounce on – for present purposes. But I do believe, as I said in my abstract, that the idea of beauty and the traditional notions of aesthetics that cluster around it, place a veil between us and the world of art as we know it today. Many of the works we still admire were certainly created when that view of art was dominant. As I’ve said, we have not suddenly banished the Titians and the Poussins and the Watteaus. But our world of art is now much larger and fundamentally different. Its basic value is not beauty and has not been beauty for at least a hundred years. Its basic value, as I’ve tried to suggest, is a close relative of the religious sense – the urge to overcome the world of fleeting appearances. Fundamentally, whether it manifests itself in a Picasso, a Rembrandt, a Buddhist head, an African mask, or the cave paintings at Lascaux, art springs, not from a search for beauty, but from a metaphysical striving, not in the impersonal sense that word assumes in much modern philosophy where “metaphysics” often reduces to little more than a series of dry, intellectual puzzles, but in the direct, human sense the word takes on when each person contemplates his or her own mortality and asks what sense a life can have when seen in that perspective. This is not to suggest that art is religion, and I haven’t had time to fully explain the distinction Malraux draws between the two. But it does help us confront the historical evidence squarely and understand why it is that in the long history of humanity, art appears to be as old as religion, if not older, and that it flourished in countless different forms across the millennia long, long before the idea of "art" ever crossed men’s minds.

(1)

This paper was written for a conference in Sydney in October 2010 which I was not ultimately able to attend. It deals with a selection of the issues I raise in my books though sometimes from a slightly different angle.

The images are from a PowerPoint show I prepared for the paper.

Apsidal vault. Madonna and Child with Twelve Apostles, Torcello Cathedral

Giotto, The Mourning of Christ. c. 1305

Botticelli , The Birth of Venus, c. 1485

Titian, Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg. 1548

|

Tiepolo, The Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra (detail). 1746-47

|

Watteau, L'Enseigne de Gersaint, (detail) 1720 |

The key concepts of Enlightenment aesthetics – concepts which continue to dominate aesthetics to the present day – were concepts that reflected the specific values and the aspirations of post-Renaissance “fine art” in the form they had assumed by the eighteenth century.

Chartres. Biblical figure. c. 1150

Malraux fully accepts that art often makes use of representation as part of its armoury of techniques, but he rejects the notion that art is essentially representation.

Malraux is not claiming that the mere fact of reduction results in a work of art. Reduction he writes, is “the beginning” of art: just the sine qua non. But it does nonetheless result in the creation of another world – a world different in kind from the one in which we live and move.

If we accept that the fundamental impulse behind what we today call art is an urge to create another world – a world that is rival to, and better than, the chaotic world of fleeting appearance – then that creative act might be harnessed to a range of possible ends and will not necessarily have manifested itself in something its contemporaries called "art".

|

|

|

The notion of “art” arose when religious belief began to fade, when there was a far weaker sense of religious transcendence, and painting and sculpture themselves invented a substitute...

“Art” is a specifically European creation, a form of the urge to create a rival world specific to Europe (at least at its origin). It produced a series of creative geniuses such as Titian, Rembrandt, and so on; but in other cultures the same the urge to create a rival world also produced creative geniuses; their efforts were simply directed to other ends.

Picasso, Weeping Woman. 1937

Mask, Vanuatu

Romanesque

sculpture: Christ in Majesty, Moissac, France.

... it does help us to confront the historical evidence squarely and understand why it is that in the long history of humanity, art appears to be as old as religion, if not older, and that it flourished in countless different forms across the millennia long, long before the idea of "art" ever crossed men’s minds.