Is aesthetics based on a mistake?

A reasonable question one might ask me at the outset is: ‘Given the wide variety of aesthetics theories advanced since the eighteenth century – and not forgetting classical precursors – is there such a thing as “aesthetics” in general? Does such a thing exist?’ The question is quite reasonable, but if we take a broad enough view of things, I think we can answer yes. Despite the multiplicity of approaches – especially on the contemporary scene – there are certain recurring themes and assumptions that continue to mark aesthetics out as an identifiable body of thought and connect it up with the tradition that took its rise in the eighteenth century.

My

aim today is to identify certain key aspects of this three hundred year

old tradition and ask some basic questions about it. In fact, as my title indicates, I want to go somewhat further

than that. I want

to suggest to you that the familiar discipline of aesthetics

that began with the Enlightenment – the discipline

that at its inception included such minds as Hume

and Kant – is based on

a mistake, that it misleads us in fundamental ways about the nature and

purpose of art, and that rather than enlighten us, it serves

principally to confuse us. The claim is less dismissive of

Enlightenment thought than it might first appear. Viewed in historical

hindsight, the mistake in question is, as I hope to show, a perfectly

understandable one, and I’m not setting out to impugn the capacities of

the philosophers who set this intellectual tradition in motion. I want,

nevertheless, to raise serious and fundamental questions about it and

suggest to you that the approach to art it offers us has now become an

encumbrance – lead in our saddle bags, so to speak – and that it’s time

we jettisoned it. In the time available today, I’m not going to be able

to present a fully rounded argument, and in particular I’ll only be

able to hint at possible alternatives to the views I’ll criticise. But

my prime intention, in any case, is to pose questions

rather than offer solutions, and I shall be happy enough

if I’m at least able to raise certain doubts in your mind about the

familiar, traditional aesthetics that has established itself as a more

or less unquestioned part of our intellectual landscape.

So what do I see as the recurring themes and assumptions that mark out this current of thought? One of these – a major one – is the familiar triad of ideas: beauty, pleasure and taste – ideas we probably all tend to connect with the discipline of aesthetics whether we’ve made a special study of it or not. I’d like to say a brief word about each of these ideas to put the issues in context.

Beauty these days enjoys slightly less favour in aesthetics than it once did and there are certain contemporary writers who have reservations about the traditional link between art and beauty. The prevailing view, nonetheless, remains close to the traditional position, and the strong emphasis Enlightenment writers such as Hume and Kant placed on beauty continues to enjoy very substantial support. So, not surprisingly, for example, there are many modern textbooks in aesthetics in which the link between the art and beauty is taken to be more or less axiomatic.

In art or in nature, beauty, according to Enlightenment aesthetics, is said to be the source of a particular kind of gratification or pleasure, traditionally termed ‘aesthetic’ pleasure, and once again this remains a prominent theme in modern aesthetics – even if the phrase ‘aesthetic pleasure’ is sometimes toned down to the more neutral formulation ‘aesthetic experience’. And then there’s the idea of taste. Art and beauty, it was traditionally argued, respond to a viewer’s sense of taste, some people having more ‘taste’ than others. And here again, in a somewhat more elevated register, we find contemporary aesthetic textbooks often dwelling on the same idea – and spending a lot of time, for example, analysing the precise nature of what Kant called the ‘judgement of taste’.

This small cluster of ideas – beauty, pleasure and taste – form part of the backbone of aesthetics, its fundamental mind-set, if I can put it that way. There’s another important factor involved as well, as I’ll argue later, but it’s nonetheless true that when aesthetics sets out to explain the purpose – the raison d’être – of art (visual art, literature, or music), these are the ideas that tend to figure prominently. Beauty, pleasure and taste belong, if I can put it this way, to the intellectual axis around which Western aesthetics has revolved since the Enlightenment and they are still very much with us today.

Now, against this background, I’d like to shift gear a little and invite you to look briefly at the history of aesthetics, and in particular at the commonly accepted account of its emergence in the eighteenth century. Briefly stated, the standard account of the event goes something like this: In the eighteenth century, the so-called ‘modern system of the arts’ came into being. The ‘fine arts’ – les beaux-arts – such as painting, poetry and music, were distinguished from the so-called mechanical or useful arts and treated as a separate form of human activity. Enlightenment thinkers, curious as always about the phenomena in the world around them, were keen to explain the nature and purpose of these ‘fine arts’ and the new discipline of aesthetics soon emerged as a sub-branch of philosophy. Drawing in a series of leading minds such as Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, Hume, Diderot and Kant, Enlightenment aesthetics essentially argued the case I’ve just mentioned: that art was closely linked to beauty, that the purpose of art was to provide a certain kind of delight, termed aesthetic pleasure, and that the capacity to respond to beauty – in nature as well as art – depended on a special faculty called a sense of beauty or a sense of taste. There were, of course, significant variations between different thinkers, but the core elements were these three: beauty, pleasure and taste – and it was on this basis, broadly speaking, that the discipline of aesthetics came into being.

Now, I have no major quarrel with this account of the emergence of aesthetics, as far as it goes. But unfortunately it doesn’t go very far. One glaring weakness is that it says so little about the historical and cultural context in which aesthetics emerged, and in particular about the functions of the activities it labelled ‘fine arts’ in earlier phases of European history and in other cultures. As a result, there is no attempt to consider the extent to which this new body of thought – aesthetics – might have been a reflection of contingent factors – factors peculiar to the European eighteenth century but possibly quite foreign to other times and other places. In a very abbreviated way, I want to spend a little time now trying to remedy this deficiency. It will involve occasional forays into the history of art – which I’ll keep as brief as possible – but if you’ll bear with me, I think you might agree that the forays are worth making.

When I say ‘the history of art’ I mean the history of what we today include under the heading ‘art’, which encompasses much more than European art since the Renaissance. There was a time – only about a century ago in fact – when the history of art simply meant the history of European art since the Renaissance plus selected Classical works. But as a visit to any major art museum reminds us, art for us today embraces the works of all cultures past and present – from Palaeolithic times onwards, via cultures as various as ancient Egypt, the Pacific Islands, ancient Mesopotamia and, of course, our own Western civilization. Now, once we recognise this, one of the first points to strike us is that we’re dealing with cultures with widely differing belief-systems, and we soon discover that, like many other ideas, the notion of art, and a fortiori ‘fine art’, is not something common to all cultures. Art, we soon learn, is a specifically European idea and even in Europe only emerged in the centuries following the Renaissance. This is not, of course, to suggest that other cultures were not rich in painting, music and poetry. We know they were. The point is simply is that other cultures, and earlier stages of our own, viewed these activities in ways different from our own, and did not create them, or respond to them, as Europe has to what it has called ‘art’. This proposition obviously raises two immediate questions: what has the idea of ‘art’ meant for Western culture , and how might we explain the fact that large numbers of objects from cultures in which the idea of art did not to exist are now regarded as art and often found today in our art museums? These are both important questions but I want to put them aside for a moment and say a little a more about the basic proposition that the notion of art – or ‘fine art’ – is not a cultural universal.

This proposition encounters determined opposition in modern aesthetics. Indeed, in my experience of the aesthetics world here and overseas, it is almost a taboo subject and it is usually opposed not by criticising it but by the simple, though very effective, means of ignoring it – pretending that no one, or at least no bien pensant philosopher of art, would ever entertain such an idea.

But of course many people have entertained such an idea and they include a range of very reputable anthropologists, archaeologists and historians. Let me just quote two or three examples. The well known anthropologist, Raymond Firth, wrote that ‘the concept “art” as such is alien to the practice and presumably the thought of many of the peoples studied by anthropologists’. The archaeologist, Gay Robins, writes that

… as far as we know, the ancient Egyptians had no word that corresponds exactly to our abstract use of the word ‘art’. They had words for individual types of monuments that we today regard as examples of Egyptian art – ‘statues’, ‘stela’, ‘tomb’ – but there is no reason to believe that these words necessarily included an aesthetic dimension in their meaning.

And closer to our own culture, the historian Paul Kristeller writes that

… there is no medieval concept or system of the Fine Arts, and if we want to keep speaking of medieval aesthetics, we must admit that its concept and subject matter are, for better or worse, quite different from the modern philosophical discipline.

Such examples can be easily multiplied. The proposition is not, once again, that painting, sculpture, poetry and music did not exist in other cultures. That claim would be absurd. The proposition is simply that other cultures did not view these activities as ‘art’, but created them for other purposes. I don’t just mean narrow utilitarian purposes, of course, but purposes different from those that post-Renaissance Western culture has associated with the notion of art. Stated as a general proposition, the claim is that painting, poetry and music can serve more than one function, and can be responded to in more than one way, and there is nothing inevitable, definitive or timeless in the way Western civilization has regarded them over recent centuries – that is as ‘art’ or ‘fine art’.

To be scrupulously fair, I should concede that certain modern writers in aesthetics have occasionally alluded to anthropological and historical evidence of the kind I’ve mentioned. But the standard response is, to my mind, highly unsatisfactory. It goes essentially like this: ‘Yes, yes, we know about that evidence, but despite what other cultures may have said or thought, they “really” or “fundamentally” regarded their works as we do – that is, as art’. In other words the evidence is trivialized, and effectively denied, a response I am sometimes tempted to describe as the appeal to the ‘aesthetic exception’. Because it is as if traditional aesthetics were saying something like this: ‘Yes, yes, we know that other cultures were often very different from ours, and as a general rule we wouldn’t think for a moment of claiming that their cultural beliefs were simply disguised variants of our own. But painting, poetry and music are exceptions, you see. In these cases, we can safely assume that, despite all the evidence to the contrary, they “really” or “fundamentally” thought and felt the same way we do’. In other words, a blatant case of special pleading, or as I describe it, the ‘aesthetic exception’.

So what would it mean to take the anthropological and historical evidence seriously? Clearly, one would need to develop a theory of what we today call ‘art’ or ‘the arts’ that successfully accounts for the fact that many other cultures regarded the activities we group under these headings in ways quite different from ours. To do that, one would need to explain what is meant by the idea of ‘art’ in the European sense, or senses, of the term, and how this notion arose in the first place. And in addition, one would need to explain why, since about 1900, large numbers of objects from cultures in which the notion of art was unknown – ancient Egypt and Africa, for example – have entered Western art museums and have come to be regarded as ‘art’, often great art, in the sense in which that term is understood today: in other words, one would need to account for the relatively recent metamorphosis of objects never regarded as art into works of art.

That is obviously a large agenda, and I’m not going to have time to cover all of it today. But nothing short of it, it seems to me, will suffice. Once we accept the anthropological and historical evidence – once, to state the matter bluntly, we cease ducking the issue– we need a theory that will explain what the West has meant by ‘art’, how the notion came into being, how other, very different beliefs and attitudes could still be perfectly comprehensible, and finally, as I say, how it comes about that we today have transformed certain objects from other cultures into what we call art.

Needless to say, aesthetics has very little to say about any of this. In fact, I know of only one theorist who has dealt squarely and convincingly with these matters, and that’s the French thinker, André Malraux. I’m not going to attempt to deal with Malraux’s theory of art in any detail today because there isn’t time. But I do want to give some broad indications of the way his thinking proceeds because he allows us to see the emergence of the idea of art, and consequently of aesthetics, in a new, and very revealing, light. And as we shall see, his thinking gives us good grounds for thinking that, despite its best intentions, aesthetics is based on a misapprehension – a mistake.

How, then, did the idea of art arise in Europe? How does Malraux explain this event?

One preliminary theoretical point to begin with. Malraux rejects the confused, if tenacious, idea that art is essentially a form of representation – that it essentially sets out to ‘represent the world’ (whatever precisely that proposition might mean). Representation, Malraux agrees, is often used as one tool among others, but the creative impulse underlying what we today call art – whether the objects in question began life as art or not – is not a desire to represent the world but to create another world – a world of a specific kind, different from the everyday world of ephemeral appearances.

Now, that proposition obviously calls for more explanation and I’ll say a little more about it later on. For the moment, though, I’d like to move directly to concrete examples and, in particular, ask how we might apply the idea to cultures in which the idea of art did not exist. A convenient example, for reasons that will become apparent in a moment, is the pre-Renaissance world of Byzantium – a culture deeply imbued with religious faith, one in which the notion of art was as foreign as it was in mediaeval Europe, and a context, needless to say, very different from the one in which Enlightenment aesthetics came into being. Applying Malraux’s basic proposition, we can certainly say that Byzantine religious images sought to evoke ‘another world’ – a world different in kind from the everyday world of fleeting appearances; but it was not a world of ‘fine art’ intended for the admiration and delectation of art lovers. It was a sacred world, a world designed to elicit not admiration but reverence. The very raison d’être of such images, in other words, was religious. They were not created for groups of appreciative art lovers in art museums – institutions which, significantly, did not exist – but for assemblies of devout worshippers in the candle-lit interiors of Christian basilicas where they evoked the mysterious presence of a transcendent, loving God.

The birth of ‘art’, in the sense Europe eventually came to understand the term, resulted, Malraux argues, from a far-reaching cultural change that began to make itself felt in the early fourteenth century – a gradual, though profound, transformation in the nature of Christian faith, involving a rapprochement between man and God. The religion of Byzantium, Malraux points out, had been a pronounced dualism: God was love, but He was also mystery, a supramundane Absolute beyond the reach of the human comprehension – an attribute reflected in the unmistakable otherworldliness of Byzantine religious images. In the early fourteenth century, however, the paintings of Giotto saw the dawn of a new dispensation – the beginnings of a rapprochement, a reconciliation, between man and God. Giotto, Malraux writes, depicted sacred events that are becoming ‘scenes in the life of Jesus’, and in doing so, ‘He discovered a power of painting previously unknown in Christian art: the power of locating without sacrilege a sacred scene in a world resembling that of everyday life.’ One result of this development was a new element of ‘naturalism’ (or ‘illusionism’) – a necessary consequence because these were scenes taking place in ‘a world resembling that of everyday life’. But the central aim was not merely to better mimic the world of appearances – a misleading claim sometimes advanced by historians of art– but, once again, to create ‘another world’ though in this case one in which the otherworldly forms of Byzantine art were replaced with something more closely resembling ‘scenes in the life of Jesus’ or what Malraux calls a ‘solemn expression of the Christian drama’.

The consequences of Giotto’s discovery were decisive. Giotto, Malraux argues, opened the way to a visual world of a radically new kind – a ‘pictorial fiction’, as he calls it, a resplendent world of ‘the imaginary’. It was not that religious feelings disappeared, he writes,

but that these were complemented by the discovery of an imaginary realm conveyed to the spectator by a power of the artist, distinct from his power of representing scenes from Scripture in that it no longer calls forth veneration, but admiration.

Developments from then on saw an enthusiastic exploration of the possibilities Giotto had opened up. By the time of Botticelli, and even more strikingly with later figures such as Raphael, Michelangelo and Veronese, there had emerged the unambiguous depiction of a transcendent world of the imaginary very different from Byzantine images – a beauteous world in which man himself seems touched by a spark of the divine, a world of God and man reconciled. Consistent with Malraux’s basic proposition, the artist is still intent on creating ‘another world’ but it is no longer a sacred world designed to elicit veneration; it is an exalted, fictional realm created for the admiration it evokes – and, crucially, one that commands authority solely through its own pictorial power, independent of any pre-existing sense of transcendence. Byzantium had been able to worship God without the aid of images – and the iconoclasts, of course, insisted it should; but the new, Renaissance ‘other world’ of nobility and beauty could only be experienced via the achievements of artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Titian, and Veronese which were its only way of coming into being.

Thus began, in Europe, the reign of what would eventually be called ‘art’ – a wholly unprecedented development. The new sense of the word ‘art’ was slow in coming, language, as often happens, lagging behind the march of events. But the change is unmistakable, and painters and sculptors were no longer regarded simply as expert craftsmen trained in special skills, but as possessors of a semi-divine power – a ‘genius’ as it came to be called – important enough to merit celebration in an account such as Vasari’s Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects – a work unthinkable in the Middle Ages and, needless to say, in other religious cultures. The new dispensation was, as I've said, accompanied by advances in the techniques of naturalism but in no case was this the primary concern. ‘[Nature’s] world is brazen and the poets only deliver a golden,’ wrote the Elizabethan poet, Sir Philip Sidney and the same was true of painting: the Renaissance artist’s ambition was not mere mimicry of appearances – Nature’s ‘brazen’ world – but the creation of an ideal realm worthy of man’s highest aspirations, a world of nobility, harmony and beauty, a transcendent world outside of which, as Malraux writes, ‘man did not fully merit the name man’.

Throughout the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this notion of art continued to grow in strength and influence. No longer destined solely for basilica, cathedral or chapel, painting and sculpture now lent their splendour – their vision of harmony and beauty – to the courts of kings and popes, who returned the favour by their encouragement, protection and patronage. Hence the proliferation of suitably noble portraits of rulers and courtiers by artists such as Raphael, Titian, and Velasquez, and hence, too, the grand alliance between art and royal power symbolised by the splendid princely palaces of the times, and above all by Versailles.

This brings us then to the eighteenth century – the crucial century for our purposes today because it saw the birth of aesthetics. By this time, as we know, powerful new forces were coming into play. Religious faith, in gradual decline since the Renaissance, was now encountering the militant opposition of Enlightenment rationalism and a further cultural transformation was in full swing. As Malraux describes it,

for the first time, a religion was being threatened otherwise than by the birth of another. In its various manifestations, ranging from veneration, to sacred dread, to love, religious feeling had changed many times. Science and Reason were not another metamorphosis of this feeling; they were its negation.

Not surprisingly, this cultural sea-change had its effects on art. While not dependent on religious belief, as we have seen, Renaissance art had always remained religion’s close ally. The subjects it transported into its golden world were as often biblical as mythological, and the kings it glorified ruled by divine right, sharing, even if obscurely, in the majesty of God. To strike at religion was therefore to strike indirectly at art, and art would need to make its adjustments.

Which is precisely what it did. Not that eighteenth century ‘fine art’ abandoned the pursuit of a transcendent world of beauty; but it modified it – brought it closer to the earth, one might say, by transforming it into a semi-theatrical world, an enchanting realm of décor, elegance and volupté. As Malraux writes, ‘between the seventeenth and the eighteenth century a crucial term had lost currency: majesty. All Europe had replaced it with charm’. The ‘other world’ of art was now much less a vision of kingly authority than one of which a painting such as Watteau’s Embarkation for Cythera might be taken as emblematic. The artist’s aim now was less to glorify than to entrance, less to praise than to please, and less to serve an ideal of majesty than to satisfy certain norms of cultured sophistication that the Age of Reason summarised in the notion of ‘taste’. The world of ‘fine art’ was now in full flower.

Now, this has been a very rapid and rather breathless coverage of four centuries of art history. But you can perhaps see why it’s so revealing for our purposes. By the time of the Enlightenment, when aesthetics as we know it was coming into being, painting and sculpture – and, of course, literature and music also – were understood in terms of a group of interlinked ideas that were specific to that moment in European history. They were ideas relating to the notion of ‘fine art’ – les beaux-arts, or the beauteous or elegant arts, as they were sometimes called. And the raison d’être of the fine arts, in the eyes of both creators and audiences, was to depict a domain of ideal harmony and beauty, to provide a special kind of delight that philosophers were soon to christen ‘aesthetic pleasure’, and to be accessible those who possessed, or were able to cultivate, their ‘sense of beauty’ or sense of ‘taste’.

In other words, the basic categories of the new discipline of aesthetics were direct reflections of the world of ‘fine art’ as it had taken form in Europe in the eighteenth century – an historically specific world that, as we have seen, had resulted from a series of transformations in European culture traceable back to Giotto. This is not, of course, to disparage the art of the eighteenth century or of post-Renaissance Europe generally. The centuries from Giotto onwards produced some of the giants of Western art – figures such as Michelangelo, Titian, Poussin, and Watteau – major figures in the world’s artistic heritage. But this was, nevertheless, painting and sculpture of a certain kind, with its own particular objectives, objectives very different from those of Byzantine or Medieval Europe, and, it should not be forgotten, from the many other cultures in which the painter’s or sculptor’s task was inseparable from religious beliefs, such as ancient Egypt, Pre-Columbian America, India, or, indeed, traditional Aboriginal Australia. It is highly probable that the interlinked ideas of ‘fine art’, ‘beauty’, ‘pleasure’ and ‘taste’ as applied to painting and sculpture would have been incomprehensible to the men and women of cultures such as these and that, to the extent they were comprehensible, would been tantamount to sacrilege. As André Malraux expressed the point in a television interview in 1975, ‘The man who made a great Romanesque statue, made it so that it could be prayed to. If someone had said, “It’s not there to be prayed to,” Saint Bernard, for example, would have replied: “Well, my friend, what’s the good of your sculpture then?” It was sculpture in the service of the soul.’

It is important to see also – although I’ll need to make this point very rapidly – that the values and objectives of post-Renaissance fine art were not only foreign to former ages and other cultures; they are also at odds with the world of art as we ourselves know it today. Here again we need to reflect briefly on art history and in particular on the enormous change that has taken place in the world of art over the last century.

For the eighteenth century, as for the centuries immediately preceding, art, in the sense of visual art, meant, exclusively, painting and sculpture since the times of Raphael and Michelangelo plus selected Graeco-Roman works such as the well-known Apollo Belvedere – that is, works that could be seen as embodying the world of transcendent harmony and beauty that was then regarded as the point and purpose of painting and sculpture. All the rest – for example, the works of Africa, Pre-Columbian America, many other non-European cultures, and the works of Medieval Europe and Byzantium – all this was not just bad art; it was not art at all. It belonged to a kind of outer darkness of painting and sculpture that could and should be forgotten. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, however, for reasons I don’t have time to consider today, the scope of the world of art began to expand – and expand immensely. Our world of art today encompasses the works of all the world’s cultures, past and present. It welcomes Pacific Island masks and Sumerian statuettes as readily as a Titian or a Watteau; and the Byzantine mosaics that the Vasari once dismissed as ‘coarse, rough, clumsy, barbaric and grotesque’ are as much part of what art means today as the Medieval sculptures that the eighteenth century often plastered over or destroyed.

In short, our modern notion of art is governed by principles quite different from those that underpinned the world of ‘fine art’. Not that we have rejected the art of Raphael, Titian, Tiepolo and Watteau. By no means. But our world of art also welcomes objects of a very different kind – objects that were not created as embodiments of a world of transcendent harmony and beauty, and, importantly, objects that the eighteenth century, and the Enlightenment minds that laid the foundations of aesthetics, would have rejected out of hand as beyond the pale of art.

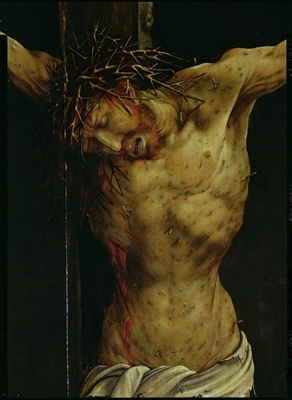

Confronted with this very different world of art, modern aesthetics has reacted by a kind of uneasy and irresolute retreat: unwilling or unable to relinquish its traditional categories, it has nevertheless attempted to preserve their plausibility by drastically diluting them. The notion of beauty, for example, has been almost entirely emptied of substance, becoming a kind of vague, will-o-the-wisp, abstraction so ill-defined that one might arguably ascribe it to almost anything. So that, for example, in contemplating Grünewald’s agonising depiction of the Crucified Christ, or a sinister Pacific Island mask, one might be urged simply to notice the ‘beautiful form’ of the work and somehow overlook the rest. This kind of thing, to my mind, is wasted breath. It’s fig leaf desperately trying to conceal an aesthetics that has reached a state of intellectual exhaustion – part of the reason, I suspect, why contemporary aesthetics is showing signs of disintegration. Objects such as these are certainly powerful works of art, but to ascribe this power to qualities of beauty, and to argue that they afford a species of ‘aesthetic pleasure’ is, to my mind, to do violence to the notion of beauty and to mislead us about the kind of mysterious fascination – something quite different from aesthetic delectation – that works of this kind exert. Cases such as these illustrate very clearly, to my mind, that the traditional categories of aesthetics are no longer adequate to the world of art as we now know it, and frequently serve simply to confuse us. Instead of assisting our responses to art, they effectively stand between us and art.

My time is fast running out but before I conclude there is one further issue I would like to mention, even if, again, my comments must be very brief. I have argued that the notion of fine art on which the foundations of aesthetics were laid was an historically contingent notion, quite foreign to earlier, pre-Renaissance periods of European culture and to non-European cultures. I want to go a step further now and suggest that the very intellectual categories in which this eighteenth century notion of fine art were explained by the new discipline of aesthetics were themselves historically contingent and by no means self-evidently appropriate to the task.

A little while ago, I quoted André Malraux’s comment about the Enlightenment attack on religion where he writes that ‘In its various manifestations, ranging from veneration, to sacred dread, to love, religious feeling had changed many times. Science and Reason were not another metamorphosis of this feeling; they were its negation.’ I find this remark very perceptive. Expressing the point another way, one might say that Enlightenment thought is profoundly anti-metaphysical. Not that philosophers of the period abandoned discussion about the existence of God, his attributes etc; but there was nonetheless, as we know, a widespread view that religious belief, in anything but abstract deistic forms, was little more than superstition. So Enlightenment ‘metaphysics’ quickly became a series of sophisticated intellectual puzzles about metaphysical topics – as it often is in philosophical ‘metaphysics’ today – rather than an individual’s meditation on the meaning of his life and death. The change here had been amazingly rapid. One has only to glance through Voltaire’s comments on Pascal’s Pensées – which reads like a dialogue of the deaf – to see how completely what Malraux’s terms ‘religious feeling’ had evaporated, and how incomprehensible metaphysical questions, in the personal, Pascalian sense, had become by the eighteenth century.

The Enlightenment’s central preoccupations, I would argue, were not metaphysical (in the sense I’ve described) but psychological and epistemological. That is, the concern was no longer ‘What significance can my life have given that death will end it?’ but ‘How am I constituted as a human being? How do I acquire knowledge of the world? (What, for example, are the respective roles of reason and the senses?) And how might a being constituted as I am maximise his happiness on this earth?’ In other words, attention had turned decisively to the here-below and to the part played by the different forms of cognition in the new post-religious model of human nature that was coming into being.

Now it’s a crucial, in my view, to recognise that this was the intellectual climate in which aesthetics came into being. There is not the slightest trace of metaphysical thinking in Enlightenment aesthetics. The orientation is unwaveringly psychological and epistemological. We only need look at the kinds of questions aesthetics has traditionally asked about art – and typically still asks today. It asks what kind of knowledge art provides. It asks if art appeals to the senses or to some combination of the senses and other human faculties. It asks about the psychological effects of viewing works of art – a question which, incidentally, is currently experiencing a new lease of life with the fashion for so-called neuro-aesthetics. And so on. And these questions are typically answered in terms of the triad of ideas which, as we have seen, Enlightenment aesthetics took over from the concept of fine art as then understood – beauty, pleasure and taste – beauty being the trigger for the psychological reaction of ‘aesthetic pleasure’, and the judgement of taste being the epistemological channel by which beauty is recognised. In short, the philosophical categories in which Enlightenment aesthetics formulated its explanation of ‘fine art’ faithfully mirror the intellectual preoccupations of the time. Art had nothing to do with metaphysical issues – indeed that question was never raised. Art was about epistemological and psychological matters – the forms of human cognition, the constituent elements of ‘human nature’, and how they functioned. Aesthetics began as a sub-domain of the Enlightenment’s central philosophical preoccupations – which is where it essentially remains to this day.

Someone might ask, of course, if an account of art in metaphysical terms is even possible and what it would look like. Time will permit only the briefest of answers and I will limit myself to two points.

First, we should not forget the alliance between art and religion that has been a feature of so many cultures throughout the long millennia of human history. ‘How easy it is,’ writes André Malraux, ‘to imagine a history of art in which the Renaissance would be only an ephemeral humanist accident!’ This is not, of course, to suggest that the link between art and religion is in some way inevitable: it clearly is not. Nor is it to imply that art and religion are in some way ‘the same thing’: obviously they are not. But it does suggest that the metaphysical concerns of religion are readily compatible with art – that there is something in the nature of art that can readily ally itself with, and help express, the characteristic preoccupation of religion with questions of fundamental meaning.

Secondly, there have been certain writers in recent times – writers outside the domain of aesthetics, needless to say – whose thinking about art is clearly built on metaphysical foundations. The most important of these – the thinker who has explored this approach most systematically – is undoubtedly André Malraux, whose theory of art underlies a lot of what I’ve said in this paper. Malraux, as I mentioned earlier, rejects the commonly-held view that art sets out to ‘represent the world’. The creative impulse underlying what we today call art – whether the objects in question began life as art or not – is, he argues, a metaphysical aspiration – a desire to create another world, a world of a specific kind, different from the everyday world of ephemeral appearances. The notion of ‘another world’ is, of course, prone to cause some uneasiness in the matter-of-fact intellectual culture we inhabit today, but in Malraux’s case such misgivings would be unwarranted because the theory of art he builds on this foundation is not only clear and systematic but, to my mind, far more fertile and helpful than the approaches provided by traditional aesthetics. Not the least of its advantages is that, as we’ve seen, it allows us to understand the original emergence of the notion of art, and the function of those activities we now include under the rubric art in cultures (such as Byzantium) in which the notion of art was non-existent. But I will leave this matter there. I mention it only to make clear that an account of art framed in metaphysical terms is perfectly possible, and that there is certainly nothing inevitable or preordained in the epistemological and psychological orientations that have governed the course of traditional aesthetics since the Enlightenment.

I have not left myself time for a proper summing up but let me just make a couple of final points.

The aim of my analysis has not been to suggest that the notions of beauty, pleasure, or taste are somehow inherently suspect, and to be avoided at all costs. In everyday life, we can call something beautiful just as legitimately we can call it elegant, or grotesque, drab and so on. And many things give us pleasure of different kinds. Nor am I suggesting that these ideas were not, in many respects, appropriate to the art of the eighteenth century and to the cultural expectations that surrounded it. The paintings of Watteau and Fragonard, for example, fit very readily into a notion of art conceived in those terms. The wrong turning taken by philosophical aesthetics, in my view, was to take the particular for the general – to treat the conception of ‘fine art’ operative in the eighteenth century as indicative of the nature of art generally. And then, of course, there was the further dubious step I’ve discussed of assuming that art had nothing at all to do with metaphysical concerns and that its nature and purpose could be fully explained via the dominant philosophical concerns of Enlightenment thought.

My purpose in advancing these

arguments, I should stress, is not merely to score intellectual points,

although I don’t think they’re especially difficult to score in this

case. A major part of the raison d’être of

aesthetics, to my mind is to help us understand art – that is, to help

us understand its place in our lives, why in fact we ‘have it’, so to

speak, and even how it might play a part in reassuring us that life is

worth living. Traditional aesthetics, in my view, has long since ceased

to perform these functions in any significant way. Not only has it lost

touch with the world of art as we now know it, but try as it might, it

can never quite escape its origins: it can never quite avoid

trivializing art by representing it as a kind of aesthete’s playground

– a privileged domain for those smitten with the so-called ‘aesthetic

pleasures’ of art. The possibility that art may have larger purposes

and a deeper human significance is routinely excluded, and the reason

for this, in my view, is that, at a fundamental level, aesthetics

remains straightjacketed in a conception of art inherited from the

eighteenth century. Hence the question I put before you very seriously:

Is aesthetics based on a mistake?

This is a paper I gave at a seminar for the School of

Cultural Inquiry at the Australian National University on 22 August

2011.

Due to time limits I was not able to develop all aspects of argument as

fully as they need to be but I think the general direction of my

thinking is clear.

(The title of my talk is similar to that of a 1952 essay by William

Kennick which is still quoted and anthologised from time to time. The

title, however, is the only point of resemblance. The grounds on which

I question the value of aesthetics are quite different from Kennick's.)

I want to suggest that the familiar discipline of aesthetics that began with the Enlightenment – the discipline that at its inception included such minds as Hume and Kant – misleads us in fundamental ways about the nature and purpose of art, and that rather than enlighten us, serves principally to confuse us.

I have no major quarrel with this account of the emergence of aesthetics, as far as it goes. But unfortunately it doesn’t go very far. One glaring weakness is that it says so little about the historical and cultural context in which aesthetics emerged...

... like many other ideas, the notion of art, and a fortiori ‘fine art’, is not something common to all cultures. Art, we soon learn, is a specifically European idea and even in Europe only emerged in the centuries following the Renaissance.

...‘the concept “art” as such is alien to the practice and presumably the thought of many of the peoples studied by anthropologists’.

The birth of ‘art’, in the sense Europe eventually came to understand the term, resulted, Malraux argues, from a far-reaching cultural change that began to make itself felt in the early fourteenth century…

... it is no longer a sacred world designed to elicit veneration; it is an exalted, fictional realm created for the admiration it evokes – and, crucially, one that commands authority solely through its own pictorial power, independent of any pre-existing sense of transcendence.

The artist’s aim now was less to glorify than to entrance, less to praise than to please, and less to serve an ideal of majesty than to satisfy certain norms of cultured sophistication that the Age of Reason summarised in the notion of ‘taste’. The world of ‘fine art’ was now in full flower.

By the time of the Enlightenment, when aesthetics as we know it was coming into being, painting and sculpture – and, of course, literature and music also – were understood in terms of a group of interlinked ideas that were specific to that moment in European history.

the basic categories of the new discipline of aesthetics were direct reflections of the world of ‘fine art’ as it had taken form in Europe in the eighteenth century

Confronted with this very different world of art, modern aesthetics has reacted by a kind of uneasy and irresolute retreat: unwilling or unable to relinquish its traditional categories, it has nevertheless attempted to preserve their plausibility by drastically diluting them.

... the traditional categories of aesthetics are no longer adequate to the world of art as we now know it, and frequently serve simply to confuse us. Instead of assisting our responses to art, they effectively stand between us and art.

There is not the slightest trace of metaphysical thinking in Enlightenment aesthetics. The orientation is unwaveringly psychological and epistemological. We only need look at the kinds of questions aesthetics has traditionally asked about art…

the philosophical categories in which Enlightenment aesthetics formulated its explanation of ‘fine art’ faithfully mirror the intellectual preoccupations of the time.

The wrong turning taken by philosophical aesthetics was to take the particular for the general – to treat the conception of ‘fine art’ operative in the eighteenth century as indicative of the nature of art generally. And then there was the further dubious step of assuming that art had nothing at all to do with metaphysical concerns and that its nature and purpose could be fully explained via the dominant philosophical concerns of Enlightenment thought.

... aesthetics remains

straightjacketed in a conception of art inherited from the eighteenth

century.