Time:

The Forgotten Dimension of Art

One possible reaction to the title of my paper

might perhaps be this: ‘Why describe time as a forgotten

dimension of art? After all, quite a lot has been written on the

subject. Some philosophers of art have examined ways in which the

passing of time is represented in films or the novel. Some have

distinguished what they call “temporal arts”, such as music, which they

compare with, say, painting, in which time seems to play a lesser role.

And there have been other discussions along similar lines. So why,

someone might say, do you describe time as a “forgotten

dimension” of art?’

My answer is that

my concern is of a more fundamental kind. My concern is not the

significance of time in this or that work of art, but the general

relationship between art and time: not the various functions of time

within individual works, but the temporal nature of art per se

– that is, the effect of the passing of time – of history if you like –

on those objects, whether created in our own times or in the distant

past, that we today call ‘works of art’. Described in broad terms, my

topic is the capacity of works of art to endure over time – and, above

all, the way they endure. This question has

been largely forgotten. Very little has been written

about it in recent decades, and what has been written, as I’ll argue

shortly, has skirted the crucial issues. In the time available, I want

to explain carefully what I mean, and why I think the issues at stake

should not continue to be neglected.

Let me begin with

some simple observations. It’s common knowledge – a cliché, one might

almost say – that those objects we regard as great works of art seem to

have a special capacity to survive across time. It’s common knowledge,

for instance, that of the thousands of novels published in the

eighteenth century, only a tiny fraction holds our interest today, and

that for every Tom Jones or Les Liaisons

dangereuses, there are large numbers of works by

contemporaries of Fielding and Laclos that have sunk into oblivion,

probably permanently. And if we draw comparisons with objects outside

the realm of art, the point is equally true. We do not ask, for

example, if a map of the world drawn by a cartographer of the

Elizabethan era is still a reliable navigational tool, and we know that

a ship’s captain today who relied on such a map would be acting very

foolishly. But we might quite sensibly ask if Shakespeare’s plays,

written at the same time the map was drawn, is still pertinent to life

today, and we might well want to answer yes. The map has survived as an

object of historical interest, but it is no longer

applicable to the world we live in. Shakespeare’s plays, on the other

hand, are not just historical documents. They have endured in a way the

map has not.

There are endless

examples of this point and I won’t try your patience by providing any

more. Stated in general terms, the proposition is simply this: that

those objects that we today call art – whether they be (for example)

Shakespeare’s plays, the music of Vivaldi, or great works of ancient

Egyptian or Buddhist sculpture – seem to possess a special power to

endure – a power to defy or ‘transcend’ time. This observation tells us

nothing, of course, about the nature of that power

– about how art endures. I will come to that

crucial issue shortly. For the moment, I simply want

to make the point – which many have made before me – that one of the

characteristics of art, or at least great art, seems to be a power to

endure over time. The observation is, as I say, almost a cliché; but

it’s a cliché beneath which, I will argue, lie some particularly

important questions that have not received the attention they warrant.

One more

preliminary point before I move to the heart of the matter.

In a book published

in 2005, entitled What Good are the Arts, which

attracted considerable interest at the time, the author, John Carey,

writes that

No art is

immortal and no sensible person could believe it was. Neither the human

race, nor the planet we inhabit, nor the solar system to which it

belongs will last forever. From the viewpoint of geological time, the

afterlife of an artwork is an eyeblink. [1]

Now, it may be

superfluous to say so in this company, but Carey’s comment is an

obvious red herring. The belief that a true work of art ‘lasts’ or

‘endures’ – whether or not we use the term ‘immortal’ – has nothing at

all to do with a claim that it is somehow able to resist damage or

destruction. How many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of great works of

the past, one wonders, have been destroyed by wars, natural disasters,

iconoclasm, re-use for other purposes, or simple neglect? Indeed, the

very fragility of many works of art no doubt made them more

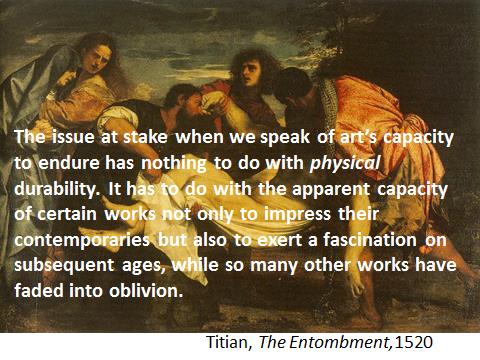

vulnerable than other objects to the ravages of time. The issue at

stake when we speak of art’s capacity to endure has nothing to do with physical

durability. It has to do with the apparent capacity of certain works —

a Hamlet, a Magic Flute, a work

by Titian, for example — not only to impress their contemporaries but

also to exert a fascination on subsequent ages, while so many other

works have faded into oblivion. It has to do with the apparent power of

certain works to ‘transcend time’ in the sense that, unlike so much

else in human culture — from the latest fad, to beliefs about the

nature of the gods and the universe — they continue to seem alive and

important, and escape consignment to what one writer colourfully, but

very aptly, terms ‘the charnel house of dead values’.[2]

Now, I’ve been using the terms ‘lasting’ and

‘enduring’ in a loose and general way without asking what exactly they

mean in the context of art. So I’d now like to turn to this question.

That is, I’d like to look at the vital question I foreshadowed a moment

ago of how art endures – how,

exactly, it ‘transcends time’.

It’s important to

note, firstly, that despite its neglect in recent times, this question

has a lengthy and important history in European culture, and without doubt the most

influential answer has been that art is ‘eternal’, ‘timeless’, or

‘immortal’. This idea pre-dates the birth of aesthetics, of course. It

was highly influential in the Renaissance world, and we need look no

further than Shakespeare’s sonnets to see the evidence.[3] Art defies time,

Shakespeare asserts, because it is eternal – timeless. The idea is much

more than a so-called ‘poet’s conceit’. It was a widely-held belief at

the time not only about poetry but about art in general, and it

continued to be highly influential over the centuries that followed.

We today, in our

matter-of-fact world, are, of course, inclined to smile a little at

words like ‘immortal’, ‘eternal’ and ‘timeless’, but before dismissing

them too hastily we should perhaps reflect on certain points.

First, the

proposition that art is timeless at least provided a complete

answer to the question we face. We’ve acknowledged that art has a

special capacity to endure, but in principle something might endure in

a variety of ways. It might, for example, endure

for a certain period but then disappear definitively into oblivion. It

might endure for a time, disappear, and then return – in a cyclical

way. It might endure timelessly – the alternative I’ve just mentioned.

And, as we’ll see shortly, there’s at least one other possible option.

So, by itself, the notion of enduring, important

though it is, leaves us with an unanswered question, an explanatory

gap. How, we need to know, does art endure? What is

the particular nature of its relationship with

time? Now, the claim that art is timeless provided an answer to this

question. Art, it said, endures not simply because it persists in time

in some unknown, unspecified way, but because it is impervious

to time, ‘time-less’, unaffected by the passing parade

of history, its meaning and value always remaining the same. Whatever

one may think about this solution (and I’ll shortly consider some

objections) it was at least a complete solution. It

didn’t simply claim that art endures. It explained the manner

of the enduring, and the explanatory gap was closed.

Second, it’s worth

remembering that the notion that art is timeless had a major impact on

European culture, including on our own discipline of aesthetics itself.

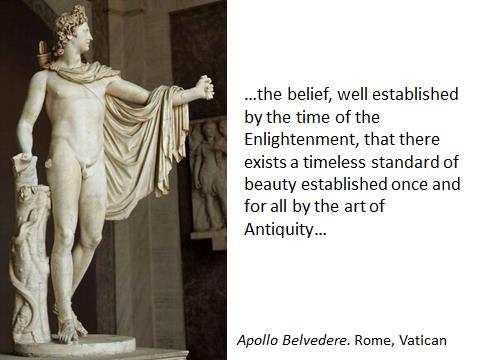

One obvious manifestation of this is the belief, well established by

the time of the Enlightenment, that there existed a timeless standard

of beauty established once and for all by the art of Antiquity –

exemplified by works such as the Apollo Belvedere

or the Laocoön. For the influential Winckelmann,

for instance, the best way – in fact the only way – an artist could

excel was by ‘imitating the ancients’.[4] Comments such as

this – and they are legion in Enlightenment aesthetics and art

criticism – take it for granted that great art somehow conforms to an

unchanging ideal beyond the reach of time; and, as we know, Kant

himself in the Critique of Aesthetic Judgement is

happy to suggest that there is such a thing as an ‘Ideal of Beauty’.[5] Just as Classical

art had endured by virtue of its ‘immortal beauty’ so, also, it was

thought at the time, any contemporary work that acceded to the ideal

realm of beauty – such as a Raphael, a Michelangelo or a Titian – could

partake of the same immortality.

Thirdly, how

confident are we that, at least at some subliminal level, we ourselves

are not still dependent on the notion that art is timeless? Critics and

reviewers often still speak of a writer ‘immortalising’ someone or

something in ‘timeless’ prose and those are clear echoes of the ideas

I’ve been discussing. It’s also arguable, I think, that the idea often

hovers in the background in modern aesthetics, especially analytic

aesthetics, as an unacknowledged assumption. The very fact that the

relationship between art and time is so seldom mentioned seems, after

all, to imply that art and time have nothing to do with each other,

that art is somehow untouched by time – which is, in effect, to say

that it is timeless. And, not surprisingly, I notice one prominent

aesthetician of the analytic school [Peter Lamarque] arguing recently

that the value we place on a work of art is due not only to its

historical significance but, in his words, to its capacity ‘to engage

the mind, the imagination, and the senses with some more timeless

interest’.[6]

I’ve spent some of my time so far in the realm of

cultural history and while I don’t want to dwell there any longer than

necessary, there’s one further issue I cannot omit. For at least three

centuries after the Renaissance, the belief that art was timeless held

the field virtually unopposed; but, as we know, this

view encountered a serious challenge in the nineteenth

century, especially from Hegel’s aesthetics, which placed art within

the historical unfolding of the Idea, and also from Marx’s historical

materialism. For many thinkers in the post-Marxist tradition today, art

is caught up inevitably in the processes of historical change. Like all

other human activities, they would argue, art bears the marks of its

historical context and plays its part in strengthening or subverting

prevailing ideologies and social arrangements. The implications of this

thinking are clear. Viewed from this perspective, the claim that art’s

essential qualities inhabit a changeless, ‘eternal’ realm removed

from the flow of history would be an idealist illusion, false to art

and history alike.

An obvious problem,

of course, is that if one accepts the Hegelian-Marxist view, one is

left without a satisfactory explanation of art’s capacity to endure,

a stumbling block that, interestingly enough, Marx himself recognised

when he wrote in the Grundrisse:

...the

difficulty is not so much in grasping the idea that Greek art and epos

are bound up with certain forms of social development. It lies rather

in understanding why they should still constitute for us a source of

aesthetic enjoyment and in certain respects prevail as the standard and

model beyond attainment. [7]

Marx’s statement

reflects a degree of deference to Antiquity that we today would perhaps

not share, but this aside, the basic point remains: we are still left

with the problem of explaining how art endures. So while

Hegelian-Marxist thinking undoubtedly inflicted a body blow to the

notion that art is eternal, it also left an explanatory vacuum. As Marx

implies, where do we look now for an explanation of

art’s capacity to endure? Deprived of the idea that art is eternal,

what alternative solution might we offer?

The principal aim of my paper is to highlight the

importance of this question rather than offer a solution. As I’ve

indicated, I think the question of the relationship between art and

time has been neglected, and it’s that situation, above all, that I

want to call attention to. But I do think there is a

solution, and although my time is limited, and my explanation will be

very sketchy, I’d like to give at least a broad indication of where I

think the solution lies.

Once we reflect a little on the history of art, we

quickly see that our world of art today is very different from that of

the Renaissance and very different, even, from that of the late

nineteenth century. Art no longer means, as it did for several

centuries, the works of the post-Renaissance West plus selected works

of Greece and Rome – the tradition denoted by, for example, the Apollo

Belvedere, Raphael, Titian, Poussin, Watteau and Delacroix.

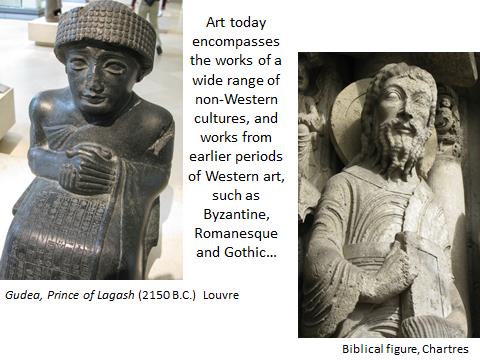

Art today encompasses the works of a wide range of non-Western

cultures, such as the ancient civilizations of Pre-Columbian Mexico,

Mesopotamia, and even of Palaeolithic times; and in addition, it

includes works from earlier periods of Western art, such as Byzantine,

Romanesque and Gothic, which were long regarded with indifference if

not contempt.

Exactly why the

world of art expanded so suddenly around 1900 is a fascinating question

– and again, I think, a neglected one – but it’s not a question I have

time to consider today. The important point for present purposes is

that once we factor in this radical change in the nature of the world

of art, the claims that art is timeless or that it is simply a creature

of history – the two basic claims I’ve discussed – both

start to look very implausible. Why do I say this? Selected objects

from non-Western cultures began to enter art museums (as distinct from

historical or anthropological collections) in the early years of the

twentieth century.[8] Yet as we know –

even if we tend to forget – Europe encountered many of these cultures well

before that, but had always regarded their artefacts simply

as the botched products of unskilled workmanship, or as heathen idols

or fetishes.[9] Moreover, if we

accept the abundant archaeological and anthropological evidence,

even in their original cultural settings these objects

were never regarded as ‘art’– not, at least, in any sense of the word

art that resembles its meaning in Western culture today. Their function

– their raison d’être – was religious or

ritualistic: they were (for example) ‘ancestor figures’ housing the

spirits of the dead, or sacred images of the gods.[10] The transformation

that has taken place over the centuries in cases such as these – from

sacred object initially, then to heathen idol or ‘fetish’, and now to

treasured work of art – is obviously very difficult to square with any

notion of ‘timelessness’ – that is, a condition in which the meaning

and value of the object is immune from change.

Time and change seem, on the contrary, to have played a very powerful

role, not only in terms of whether or not the objects were considered

important but also in terms of the kind of importance placed on them.

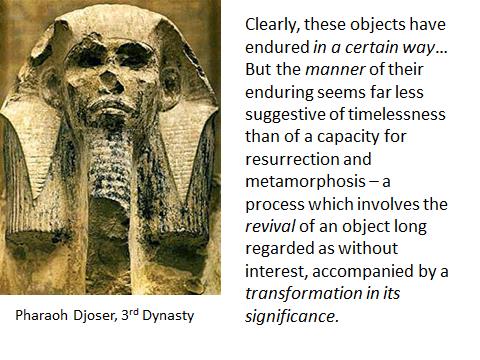

Clearly, these objects have endured in a certain way: they are not

simply creatures of history that have lost their original significance

and are now of merely ‘historical interest’ – like the Elizabethan map

I referred to. But the manner of their enduring seems far less

suggestive of timelessness than, as the French theorist André Malraux

has argued, of a capacity for resurrection and metamorphosis – that is,

a process in which time has played an integral part which involves the

revival of an object long regarded as without interest, accompanied by

a transformation in its significance.

The point is not easy to assimilate on first encounter and a further example may help clarify it.

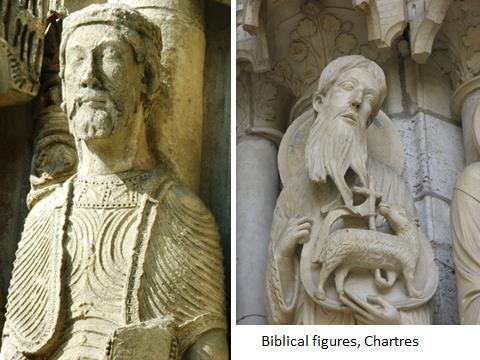

The so-called ‘pier statues’ of biblical figures on the portals of

Chartres cathedral are now widely considered to be among the treasures

of world art, on a par with, for example, the best of Egyptian or Khmer

sculpture, or the works of Donatello or Michelangelo. Yet from Raphael

onwards all medieval art was regarded as inept and

misconceived (hence, as we know, the term ‘Gothic’ with its original,

pejorative overtones) and consigned to an oblivion of indifference. The

revival of medieval sculpture as art[11] only began in

earnest in the late nineteenth century – that is, after some three

centuries of neglect and disdain. This is not, of course, to condemn

the intervening centuries, or to suggest they somehow lacked an

‘appreciation’ of art (an unpromising argument, given that the period

in question produced many of the major figures of Western art – and

aesthetics). It does, however, suggest an alternative explanation of

the relationship between art and time. It suggests that art does not

endure timelessly – unchangingly – but through a capacity to ‘live

again’, to resuscitate, despite periods of oblivion, its rebirths being

inseparable from a metamorphosis – a transformation in significance.

The statues at Chartres were not ‘art’ for the men and women of the

thirteenth century for whom they were created. They were sacred images

– manifestations of the Christian Revelation – and to place them on

equal footing with religious images from other cultures such as ancient

Egypt or the Khmer civilization, as I have just done, would, for their

original beholders, have been unthinkable and, in all probability,

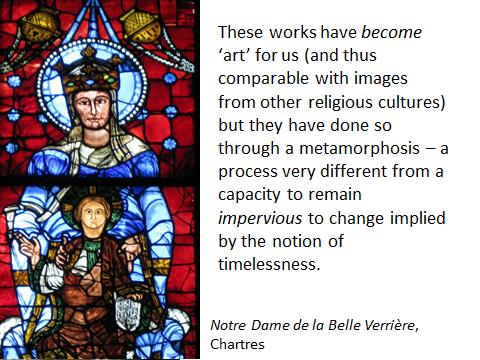

sacrilege. These works have become ‘art’ for us

(and thus comparable with images from other religious cultures) but

they have done so through a metamorphosis – a process very different

from a capacity to remain impervious to change

implied by the notion of timelessness.

These few remarks

certainly don’t do justice to Malraux’s concept of metamorphosis. But

my time is running short and in any case the central aim of my paper

is, as I’ve said, less to advocate a particular solution to the

question of the relationship between art and time than to highlight the

importance of that question. I happen to find Malraux’s position very

persuasive because it’s coherent and explains the facts as we know

them, but I will leave his ideas now so I can comment briefly on what

has been said by recent writers in aesthetics about the question of art

and time.

As I’ve indicated,

very little has been said. And even when discussion

has moved in this direction it has not, in my view, addressed the key

issues. Let me give just two examples.

Pursuing a

well-known theme going back at least to Hume, some philosophers of art

have focused on the so-called ‘test of time’. One writer, for example,

[Anthony Savile] notes that the longevity of a work of art – its power

to ‘survive over time’, in his phrase – is often seen as an indication

of its value, and he then asks whether this view is justifiable,

eventually returning an affirmative answer.

[12]

But, as we can now see, this thinking does not go

far enough. The issue is much less to know that art

– at least great art – has a power to endure; that much, surely, is

reasonably obvious. The crucial question is how art

endures – the nature of its capacity to ‘survive’.

I have listed four possible answers: Art might survive for a certain

period and then disappear definitively into oblivion. It might endure

for a time, disappear, and then return with its original meaning – in a

cyclical way. It might endure ‘eternally’ – outside time – which, as I

mentioned, is the explanation that has figured most prominently

throughout European history. Or it might, as Malraux argues, survive

through a process of metamorphosis. So, conceivably, art might

‘survive’ in a number of ways, and to focus simply on the question ‘Does

art survive?’ is to stop short of this crucial issue.

Another debate

sometimes thought to have a bearing on the relationship between art and

time is the question of whether a work of art is legitimately

susceptible to just one interpretation, or more than one. The thinking

here, I take it, is that if the answer is ‘more than one’, then a work

of art is changed by the passing of time; and if the answer is ‘only

one’ then it is not changed.[13] But this line of

inquiry is of no help to us at all. For whatever

the number of so-called ‘legitimate interpretations’, that number could

conceivably be fixed – the fixed number of meanings

that the artist, consciously or unconsciously, gave the work at its

moment of creation. And if this is so, the work is fundamentally immune

from change irrespective of the number of interpretations – just as a

diamond is, for example, despite having multiple facets. Moreover, even

if we ignored this difficulty, we are left simply with the conceptual

framework: change/no change, which is equivalent to: change or

timelessness; and for all the reasons I’ve given these alternatives do

not give us a satisfactory purchase on the problem of the relationship

between art and time. In short, as I say, this line of inquiry is not

fruitful. Whether a work of art is susceptible to one, or a more than

one, interpretation is, by itself, of no assistance at all in

understanding art’s temporal nature: it tells us nothing about the

way art endures.

A few concluding remarks:

Perhaps someone

might say to me: ‘Yes, yes, but even if we agree, how important is

this, after all? Does it really matter? Does aesthetics need to bother

about the relationship between art and time?'

My answer has two

aspects, one theoretical in nature, one more practical.

The theoretical

aspect is this. We know that art – or at least great art – endures in

some way. We

know that for every painter, composer, or writer of the past whose

works are still admired today, thousands have faded into oblivion. And

going outside the realm of art, we know there’s a major difference

between an object such as a map preserved purely for historical

interest, and a work of art, such as a play by Shakespeare, or the

music of Mozart, which still seems vital and alive today.

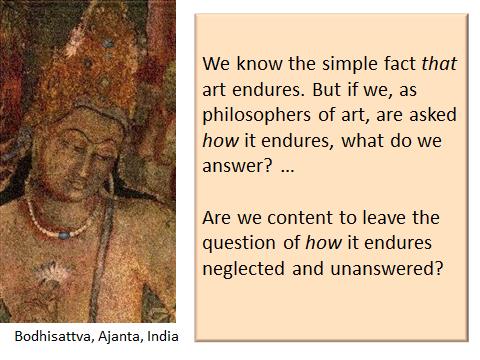

So we know the simple fact that art

endures. But if we, as philosophers of art, are asked how it endures,

what do we answer? Do we say it is timeless – eternal? Few would argue

this today, I suspect, and for good reason, as I’ve tried to show. So

what do we reply?

That art is a creature of history? But that would tell us why art is affected by time,

not why it transcends it. Do we

then try to argue that art is somehow both timeless and embedded in

historical change? But that clearly won’t do. The notion of

timelessness means what it says – outside time, immune from change. To

be simultaneously changing and changeless is not a condition one can

readily imagine.

So that’s the theoretical aspect of my answer: We know that

art endures. Are we content, as philosophers of art, to leave the

question of how it endures neglected and

unanswered?

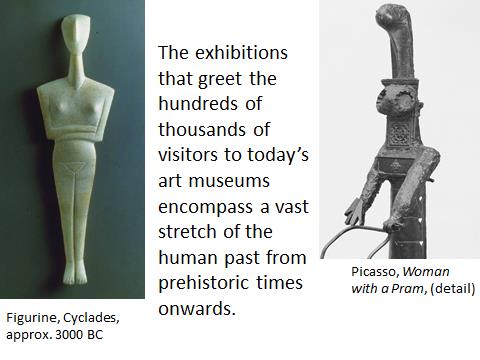

The practical issue

is this: Our modern world of art is

obviously much more than the world of modern art. The exhibitions that

greet the hundreds of thousands of visitors to today’s art museums

encompass a vast stretch of the human past from prehistoric times

onwards. And just like modern works, many works from the distant past

seem vital and alive to us despite the long periods of time since their

creation, despite the fact that so many of them did not begin their

lives as ‘works of art’, and despite the long periods during which they

were regarded with indifference or even derision. Seen in this light,

the capacity of works of art to transcend time, and the nature

of that transcendence, become very real and

pressing questions – questions posed on a daily basis to countless

visitors to today’s art museums, even if they are only vaguely aware of

them. So in simple, practical terms, we, as philosophers of art, surely

cannot afford to ignore the question of how art

endures – unless we are content to place severe limits on our

discipline’s capacity to speak to the art-loving public in useful and

relevant ways.

André Malraux once

wrote that, ‘as well as being an object, a work of art is an encounter

with time’, and this, in a nutshell, is the point I’ve been making in

this paper. Aesthetics today, as I see it, has had a lot to say about

art as an object. We’ve asked, for example, about the difference

between a work of art and a ‘mere real thing’, we’ve asked whether

works of art function as a means of ‘representation’ or not, whether

art provides a kind of knowledge and if so what kind, and a range of

other questions concerning the work of art’s condition as an object.

But we have not asked about art’s temporal nature –

the nature of its capacity to endure over time. This was once a major

theme in Western thinking about art, and I’ve briefly canvassed some

aspects of that fascinating history. Today, as I've tried to suggest, the issue is, if anything, even more important. Unfortunately, however, the discipline of aesthetics seems to have forgotten it, and our understanding of art, I would argue, is seriously impoverished as a result.

[1] John Carey, What Good are the

Arts? (London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 2005), 148.

[2] André Malraux, Les Voix du silence,

Ecrits sur l'art (I), ed. Jean-Yves Tadié, 2 vols. (Paris:

Gallimard, 2004), 890.

[3] This comment was accompanied by a slide

showing the well-known lines of

Sonnet 18:

But

thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st...

[4] Johann Winckelmann, Reflections

on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, trans. Henry

Fusseli (Menston, Yorkshire: Scolar Press, 1972), 1, 2.

[5] Critique of Aesthetic Judgement,

Book One, §17. Some writers have argued that Kant’s comments here are

inconsistent with other aspects of the Critique. That may be so; they

are nonetheless part of the work.

[6] Peter Lamarque, "The Uselessness of

Art," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism

68, no. 3 (2010): 213. Lamarque relies quite heavily on the notion of

timelessness in the concluding stages of his article, although the

issue is somewhat blurred by his formulation ‘more timeless’. In strict

philosophical terms (which is what matters here), the word 'timeless'

cannot be qualified.

[7] David McLellan, ed. Marx’s

'Grundrisse' (London: Macmillan Ltd,1980), 45.

[8] A fact that is often forgotten. African

art, for example, had to wait until the mid-twentieth century before

being admitted into the general collections of art museums. I have

discussed this issue in some detail in Art and the Human

Adventure; André Malraux’s Theory of Art. It should be

stressed that the present analysis concerns the acceptance of the

objects in question as art. Artefacts from non-Western cultures had

previously been included in cabinets de curiosités and history museums

but that is a different matter.

[9] Cf. the comment by H. Gene Blocker:

“Although primitive artifacts were known to Europeans from the time of

the great explorations of the New World and the Far East from the 15th

century onwards, and although a few pieces were admired by artists such

as Dürer and Cellini, there was virtually no aesthetic interest in such

artifacts as works of art until the early years of the 20th century.

Gold objects from Pre-Colombian Mexico and Central and South America

were melted down and the valuable raw material shipped back to Spain; a

few pieces were taken back to the home countries as evidence of the

culturally savage and barbaric state of the natives; and what aesthetic

response there was was largely one of horror at the ugliness and

brutality supposedly symptomatic of these savage, heathen works of the

devil.” H. Gene Blocker, The Aesthetics of Primitive Art

(Lanham: University Press of America, 1994), 272.

[10] I am aware that some philosophers of

art do not accept these views, arguing that no matter what the peoples

of non-Western cultures may have said or done, they “really” or

“fundamentally” regarded such artefacts as art in some sense similar to

our modern meaning of the word. There is no space to do justice to this

question here, important though it is. I have discussed it at some length in my books Art and

the Human Adventure; André Malraux’s Theory of Art and Art and Time. However,

even if one were to reject the claim that the cultures in question did

not regard their artefacts as art, the previous point remains intact –

that is, that, for centuries, European cultures regarded them as merely

the botched products of unskilled workmanship, or as heathen idols or

fetishes, never as art. In many cases they were melted down or

otherwise destroyed to recover the precious metals and jewels.

[11]

As distinct from a component

of medieval history or a picturesque element in historical novels,

developments that occurred somewhat earlier.

[12]

See Anthony Savile, The

Test of Time: An Essay in Philosophical Aesthetics (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1982). Cf: also the comment: ‘…only with the passage of time can we

become certain of the security of [artistic] value. Hence the test of

time is necessary for stable evaluations of historical importance or

worth.’ Alan H. Goldman, "Art Historical Value," British

Journal of Aesthetics 33, no. 3 (1993). See also: Anita

Silvers, "The Story of Art Is the Test of Time," Journal of

Aesthetics and Art Criticism 49, no. 3 (1991).

[13] This argument surfaces in various ways,

for example, in: Jerrold Levinson, "Artworks and the Future," in Music,

Art, and Metaphysics: Essays in Philosophical Aesthetics

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 179–214, 180, 81. Goldman,

"Art Historical Value," passim. A similar preoccupation emerges in some

of Arthur Danto’s work. Cf: “One can discover only what is already

there but has remained up until then unknown or misrecognized.” Arthur

Danto, "Artifact and Art," in Art/Artifact: African Art in

Anthropology Collections, ed. Susan Vogel (New York: The

Centre for African Art, 1988), 18–32, 19. In

all these cases, the focus is on the mere fact of change which, as

argued here, is of no help in addressing the issue at stake. (I am

leaving out of account here attempts to add an historical dimension to

‘institutional’ notions of art such as Jerrold Levinson’s idea of a

chain of ‘art regards’. This is only tangentially relevant to the

present discussion and is in any case open to serious objections. I have

outlined these in Art and the Human Adventure; André

Malraux’s Theory of Art and in Art and Time.)

This is a paper I delivered at a meeting of the Dutch Association of Aesthetics in Ghent, Belgium on 27 and 28 May 2011. It outlines key questions to be addressed in considering the temporal nature of art - a major issue which, as I say in the paper, has been widely neglected in modern aesthetics.

I accompanied the paper with a Powerpoint show which included images of relevant paintings and sculptures. A number of these are shown below.

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st...

Shakespeare, Sonnet 18

The notion that art is timeless had a major impact on European culture, including on our own discipline of aesthetics itself.

It’s arguable that the idea that art is timeless often hovers in the background in modern aesthetics, especially analytic aesthetics, as an unacknowledged assumption.

For many thinkers in the post-Marxist tradition today, art is caught up inevitably in the processes of historical change.

Once we factor in this radical change in the nature of the [modern] world of art, the claims that art is timeless or that it is simply a creature of history both start to look very implausible.

Whether a work of art is susceptible to one, or a more than one, interpretation is, by itself, of no assistance in understanding art’s temporal nature: it tells us nothing about the way art endures.

André Malraux once wrote that, 'as well as being an object, a work of art is an encounter with time'.